Why Independent Is The Watchword On The Water As Swimming Prepares To Launch Integrity Unit

Weekend Essay – Editorial – The critical need for Independent authorities to underpin complaint and investigation procedures and processes is highlighted today by the following FIFA-football exposé in The Guardian:

The world’s game, a global scandal: the struggle to be heard in football’s sexual abuse crisis – At all levels and in every corner of football, allegations of harassment and worse are being uncovered. But Fifa and the game’s authorities are ill-equipped to tackle them – by Ed Aarons, Suzanne Wrack and Romain Molina, with additional reporting by Alex Cizmic

“They are from countries where the accused are often part of the same power structure, making it even harder for them to report their abuse. And persuading Fifa to listen may be the start of a tortuous process for them and their families,” the reporters write.

Those two sentences in a long read of horrible experience cut to the heart of the crisis and make the feature essential reading for all in swimming at a time of reform, the establishment of Integrity Unit and whistleblower policies and procedures.

Independent. Meaning: “…free from outside control; not subject to another’s authority.”; “not depending on another for livelihood or subsistence”, just two definitions highly relevant to whether a critical aspect of the reform processes underway in swimming will take aquatics to a better place far from a culture of omertà and conflicts of interest and self-serving governance that have been all too present for all too long at the top tables of the sport and the grace-and-favour committees and commissions that prioritise politics and treat the need for independent, professional minds and skills as an afterthought to be wrecked in small measures as a useful masquerade for seriousness and high standards.

The Guardian‘s investigations, plural because the work involves long-term monitoring and then compiling of information of separate cases, is relevant to all sport. The cases raised in the exposé have one thing in common beyond the presence of abuse: the survivors felt they could not trust their sports authorities.

That may be because leaders were involved in the abuse or it may be because leaders did not follow independent and robust investigative procedures, among their failures an absence of any mechanism or, it appears, will, to make immediate suspension an essential part of process along with strict observance of confidentiality during investigation on the way to a decision, be that a referral to police or an independent integrity unit where investigative skills and professional competence go well beyond what the volunteer leaders of sports organisations might be expected to have in their own tool kit of talent.

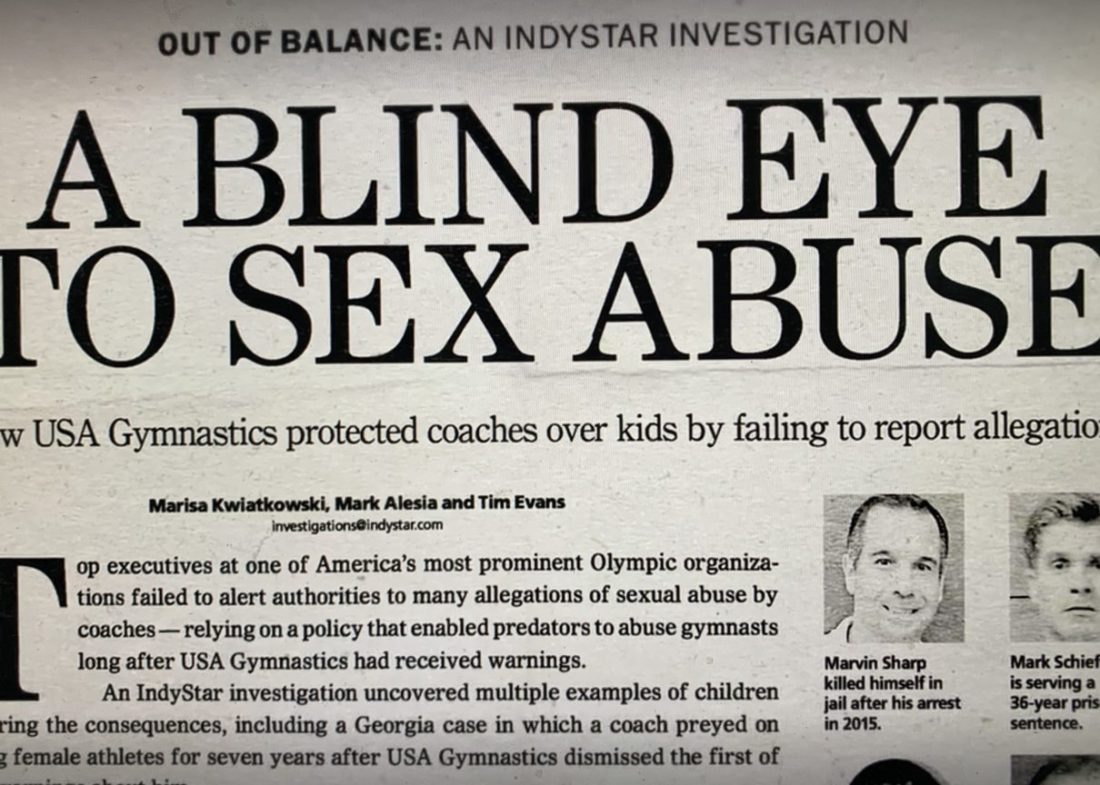

Swimming is a sport where sexual abuse and harassment have long been too present, much mishandled. Athlete A, the USA Gym scandal, the galling case of George Gibney and how such things relate to the strength of “The Swimming Voice”, the recent scandals in South Africa and much else contribute to the realm of sport being seen as a safe haven for rogues.

While The Guardian‘s football exposé makes much mention of African nations and Afghanistan and places in the world where aquatics is very much development niche sport, sexual and other forms of abuse and harassment in aquatics has often been found among the leading nations in sports such as swimming.

The United States, Australia, Britain, Germany, Ireland, South Africa, China, and, going back decades, the GDR and Soviet Union are on a list of nations with the likes of Kenya and other development nations that have been afflicted by abuse cases, including sexual crimes and allegations, involving officials and coaches and athletes who are often minors or very young adults.

The courage and determination of survivors, Deena Deardurff Schmidt a towering example of the abysmal treatment victims of abuse have had to endure, and the vigilance and work of Safe Sport advocates such as Nancy Hogshead-Makar, the 1984 triple Olympic champion in swimming, and coach Dia C. Rianda, have highlighted the need for a different approach to keeping rogues away from the water.

Hogshead-Makar and Rianda were among the many advocates, athletes and others who pressed the U.S. government to get the Empowering Olympic, Paralympic, and Amateur Athlete Act (S2330) on the statute books, the law of the land now able, should it have reason and will to do so, to sack the entire National Olympic Committee if they fail to protect athletes.

Many have never been protected, to the shame of their guardians and the stewards of swimming. Advocates point out that the adoption of Safe Sport policies at USA Swimming happened under pressure from outside, 20 years after a draft of recommendations for protecting young athletes from abusers was drawn up by an “Abuses Committee” at USA Swimming but then shelved until Deardurff Schmidt made public the complaints known to swimming authorities and coaching peers since the late 1970s.

Deardurff Schmidt, cited for her role in coaching beyond her racing days, is not in the Hall of Fame because she won a gold medal at the 1972 Olympic Games. The coach she says sexually abused her when she was aged 11-14, Paul Bergen, remains in the Hall of Fame, swimming authorities having found no mechanism to investigate, interview, call to account and come to a view and decision down all the decades when the man was a national-team coach and citizen and resident of the United States.

Bergen has put Deardurff-Schmidt’s testimony down to “a misunderstand” in an AP interview back in 2010.

Of late, Hogshead-Makar has had good reason to get involved in the controversy of transgender athletes and their impact on women’s swimming. It is a situation involving various forms of abuse of athletes in the same pool, the adults and decision-makers in the room unwilling to see the elephant or even acknowledge swimming history highly relevant to the impact of androgenisation in women’s sport even when all competitors are biological women, an issue I first raised in 2013.

Almost a decade has gone by and rule-makers are to be found lost, shrugging in the complexities of their own failings and, apparently, taken by surprise.

Some moments of surprise are more understandable, the invasion of Ukraine by Vladimir Putin sinking sports governors into a cultural shock long overdue: almost all have been too ready to cite the Olympic Charter and the need for neutrality and “no politics” in one breath, when putting athletes in their boxes, while sipping champagne with and enjoying the largesse of dictators and an assortment of other political leaders with questionable records. Such things never always come with a moment of pay back.

It’s taken a war and the misery of many to bring sports leaders to their senses and strip Putin of the Olympic Order and the FINA Order. Let lessons be learned – and let it not be said that sports leaders were not warned.

The list is long when it comes to ‘why we can’t act’ when abuse (various forms) raises its ugly head, including “nothing we can do if there’s no criminal prosecution” even when knowing that any statute of limitation makes that highly unlikely in many cases. Such statutes do not mean there is nothing that can be done – and smart lawyers know it.

Nothing on the “can’t do” list is of any relevance in the absence of effort to change rules of the sport in the hands of those very same decision makers.

Reform is underway and as Francois Carrard (RIP), the Swiss lawyer long steeped in the Olympic Movement and all its victories and vanities, put it as chairman of the FINA Reform Committee of 12 that made recommendations now accepted by the FINA Bureau (board) and currently being implemented:

“[FINA] shall not leave a single stone unturned in the way in which it looks to the future. After all, reform is not a single event. It is a process that will test out patience.”

Francois Carrard

Spot on. The issues can be complex. Indeed, the nature of rogues and roguery make it so. A change of approach is required.

In the past decade, survivors have being deposed and dealt with by lawyers and the sports organisations they earn fat fees from, for advice and handling, as if they were in the problem, not the victim.

There are solid reasons to believe that the FINA reform process, one which will set the tone for all organisations in the chain of swimming command, is serious and genuine. Signing up to standards, like those LEN recently adopted, is a paper exercise. What follows is the next level, the one that considers the independence of the standard setter, its paid-for ratings service and, most importantly, the checks and balances, the assessment and the transparency of process beyond the all-too cosy official signing moments. There is much work to be done, many questions to answer and much culture to shift.

FINA Reform is being led by president of FINA since last June, Husain Al-Musallam, and new director, Brent Nowicki, former counsel for the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and a man at the table for the Sun Yang process.

There is a long journey ahead and there is a commitment to independent process. Applications are now open for positions on the Aquatics Integrity Unit. Very few regulators in the sport have adequate – or indeed any – whistleblower policies and trusted structures in place; few have genuinely independent reporting and investigative procedures as part of their governance pillars.

All eyes on the procedure for selecting and appointing those who will serve on the Integrity Unit, in this sense: of late I had reason to look through the four tiers of a reporting structure that complainants in a particular sport could turn to. If they could not trust those involved at tier 1, because of likely connections with the subjects of complaint, the reporter could go to tier 2, then tier 3 and as a last resort tier 4. Each tier was supposed to be more remote from the powers that be, from the status quo, from the decision makers.

Except, that was not the case. It was very clear to me that all people from tier 1 to tier 4 had relatively strong connections, all knew each other and all had at some stage in their careers as sports leaders, voluntary or paid, had sat in the same decision-making forums together or worked on a pool deck together, and so on and so forth.

Trust in an Independent reporting and then handling process is critical and that must be built into the Integrity Unit from the get go. David Howman, the head of the Athletics Integrity Unit, had wise words for swimming on the subject of “independent” when he spoke to SOS last year.

The Guardian investigation is about FIFA and football world, and there’s much mention of African nations and Afghanistan and places in the world where aquatics is very much development niche sport.

But as you read and weep, apply it to all nations, big fish and small and ask how strong the reporting procedures are, how much trust we can have in them and whether the people and tiers you would be asked to report to – if they exist – are layered with professionally trained folk working in separate compartments or whether there are volunteers in the midst without adequate training and skills and only there because a connection or mate in the sport put them there. Only there because the politics and the votes demand they must be there.

The Integrity Unit cannot be like any other body or committee that ever existed in swimming governance. It must be as independent as independent can be. It must be a place where anyone in aquatics with an issue or complaint to raise, any subject, can turn to knowing that their trust will not be misplaced.

The world’s game, a global scandal: the struggle to be heard in football’s sexual abuse crisis.