When Aussie Swim Ace Michelle Ford Spoke The Athletes’ Voice For The First Time To Olympic Bosses With Coe & Bach

Michelle Ford, the Olympic 800m freestyle champion and bronze medallist behind two GDR swimmers in the 200m butterfly for Australia in 1980, shares extracts from her forthcoming autobiography on the 40th anniversary of an important milestone in Olympic history, described in a chapter of her work entitled The Athletes’ Voice

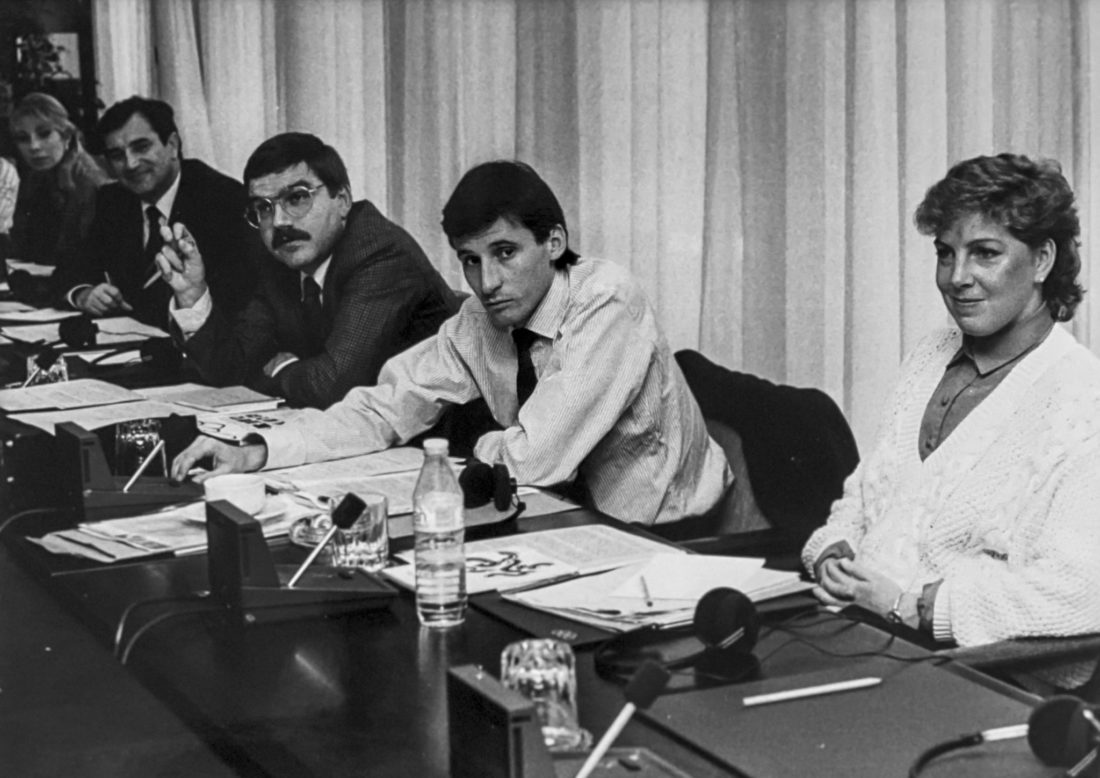

Today, as the Swimmers’ Alliance gets set to meet FINA, marks the 40th anniversary of the moment athletes first got to speak their voice to Olympic bosses at Congress, then 19-year-old Australian swimmer Michelle Ford breaking the mould alongside British peer-to-be Sebastian Coe and IOC president-to-be Thomas Bach.

That a swimmer – and a teenage woman at that – was at the very heart of the movement to have the athlete voice heard by those in governance at the height of the most appalling era for women in Olympic sports history speaks volumes for the determination and character of Ford.

Four decades on, there remains much work to do, including IOC acknowledgement of the Sporting Crime of the 20th Century through any form of reconciliation ruling that would compensate for almost two decades in which the German Democratic Republic’s State Plan 14:25 systematic doping program clobbered the rest of the world of women’s on a regular basis at Olympic, World and European levels.

FINA, the International swimming federation affiliated to the IOC, honours to this day several GDR officials, including Dr. Lothar Kipke, the former head of its Medical Commission, despite the fact that in 2000 he was criminally convicted of aiding and abetting bodily harm of minors.

In 2014, the Press Commission of FINA voted unanimously to support a call from SwimVortex, the site that is State of Swimming today, to consider a reconciliation process for victims of State Plan 14:25, both those robbed of their rightful rewards in the pool and those robbed of their health by the large dosages of androgenising steroids they were given.

Many thousands of swimmers – from as young as 13-14 years old, some younger still – were fed a toxic mic of performance-enhancing substances so that they would be ‘winners’ in their roles as “ambassadors in tracksuits” to the DDR. Some who were never seen nor heard of beyond the Berlin Wall were used as lab rats to test the fitness and effect of certain drugs before they were given to athletes chosen for state stardom.

The Press Commission has to this day received no reply from the FINA leadership, one of several reasons why this author resigned from that body in the same year. Water under the bridge but the issues remain – and remain unresolved, questions remain unanswered and the search for solutions remains a wasteland.

The new FINA leadership now has a chance to right one of the biggest wrongs in sports history: it has an American director and will soon employ Mike Unger, who has announced to his home federation that he is leaving his long-term and well-remunerated post at USA Swimming to work at the international federation.

American men will therefore occupy three of the most senior positions of power at FINA, including two paid positions and one executive role subsidised by very generous payments (called per diems), with all costs covered. The test of whether sincerity was in play when highlighting the plight of American women swimmers at the 1976 Olympic Games in the documentary film “The Last Gold” is now well and truly on.

What point The Last Gold if reconciliation and healing play no part, if the women affected – both sides – continue to be ignored by those in positions of power?

Go back to September 28, 1981 and we hear an impassioned speech addressed to the IOC at the XIth Olympic Congress in the German spa town of Baden-Baden. The Olympic Movement was much in need of healing and much greater awareness of athlete wellbeing.

Ford was a member of the key group that sat up through the night this week 40 years ago to write, ready and finalise the speeches that athletes would deliver to the IOC for the first time at Congress. After five shorter addresses from athletes, one of them the words written by Michelle Ford and delivered by the great Kenyan runner Kip Keino, Seb Coe spoke to Olympic bosses on behalf of athletes on the final day of the gathering in Baden-Baden.

The speeches were described by Jacques Rogge, when president of the IOC, as “the start of a revolution”.

Each speech was not personal but collective and reflected the views of 25 Olympic medallists who spent 10 days, chewing the cud of issues that affected athletes, including doping and boycott, Moscow among the Games where results were skewed by unfair and damaging absence and winners were unfairly damaged by the same absence and their decision to compete.

A year after claiming the only gold medal claimed by a western woman in the pool at the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games, Ford was one of the 25 invited to the Congress – and became one off those who compiled and crafted the messages that Olympic bosses would hear for the first time. Here are extracts from her upcoming autobiography, one SOS has had sight of and recommends to all readers and those with an interest in swimming and athlete history.

In the Words Of Michelle Ford 40 year on: memories of September 1981

“We wanted a seat at the table, the right to self-determination, the right to inclusion and equality. We wanted our voice, the athletes’ voice, to be heard.”

At 19, she was the baby of a group of athletes mostly under the age of 30. They would prompt the IOC to make the first small steps towards “putting athletes at the centre of the Olympic Games”.

If that sounds, at best, faintly ludicrous (how could the Olympic be about anything else!), Ford notes that the group wrote speeches and delivered them in Baden-Baden at a time when athletes felt that they played second-fiddle to governors and politics, ignored, bypassed and hit by doping and boycotts without hope of having their voices heard at the top tables of sports governance.

Ford says: “We, the athletes, were left with a sense of helplessness. The issues had affected us all – everybody who was there in Baden-Baden … there was a canyon between the full-time sports programme for athletes in many Soviet Bloc countries and those of us who, like me, needed to fit training in and around work or school”.

The doping that kept Ford from being a triple champion at Moscow 1980 – she was also fourth in the 400m freestyle, behind three GDR swimmers – affected women swimmers from 1973 through to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 (and a little beyond, too).

Eight years prior to the moment that sparked German reunification, the 25 athletes gathered in Baden-Baden referred to the advance of the GDR and payments and benefits made to Soviet-bloc athletes as “the most shameful abuse of the Olympic ideal”at a time when amateur rules were still very much in force.

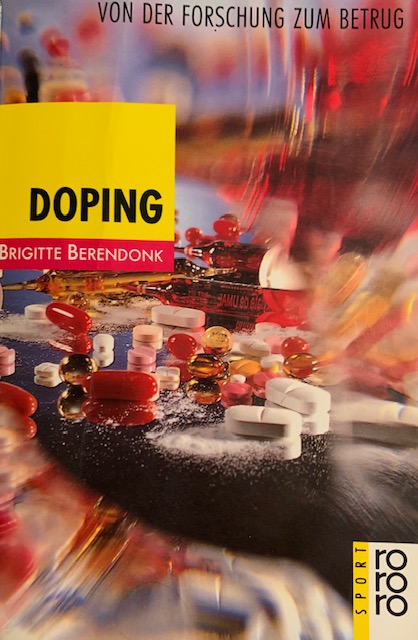

They spoke a decade before the horrid depth of State Plan 14:25 was revealed by Brigitte Berendonk and her husband Prof. Werner Franke through the Stasi (state police) papers they had helped to save from the shredders. The documents detalied the names of athletes doped, specific doses of named substances, such as Oral Turinabol – and the identities of many of the architects, engineers, pimps and pushers of systematic doping.

Despite the overwhelming evidence available, neither the IOC nor the likes of FINA and its member federation the German swimming federation, the DSV, sought to change the results and records of almost two decades off swimming in which GDR success was fuelled by banned substances.

Back in 1982, the IOC was a man’s world, women a rarity at the top level of governance across the whole realm of sport. Writes Ford:

“The inclusion of women in the Olympic movement was so important. Women’s events counted for only a quarter of the Olympic programme at that time, there were no female IOC members, nor were any to be found on any of the International or National Federation Boards even though the Olympic swimming programme, for example, was almost identical for women and men. The imbalance across the spectrum of sports was startling.”

Michelle Ford – glory in the Olympic 800m freestyle for Australia – image – ©Michelle Ford

Ford was one of six women athletes invited to the 1981 Congress. Alongside her were Yuko Arakida, Japanese volleyball Olympic champion in 1976; Svetlana Otzetova, Bulgarian Olympic rowing champion the same year; Elizabeth Theurer, Austrian Olympic equestrian champion of 1980; and, from winter sports, Soviet 1980 Olympic luge champion Vera Sosulia, and Irene Epple, the West German Alpine Olympic silver medallist in the same years.

Six out of 25. That was big progress, as one one woman sitting up through the night helping write speeches to be delivered by blokes who would become leaders in the sports world – Bach head of the IOC and Coe head of World Athletics these days.

Ford recalls her first encounter with Olympic governance: she was collected at Frankfurt Airport by a personal chauffeur and driven in a black Mercedes to the athletes’ hotel in Baden-Baden: “Every detail of our 10-day itinerary was precisely ordered, everything was organised to the second.”

In her forthcoming autobiography, Ford writes:

“On September 21, two days before the official opening of the Congress, the 25 athletes, some with trepidation and others with gusto, met for the first time in the athletes’ designated area, the International Hall.

“A welcome speech introduced our appointed staff and our official interpreters, followed by an overview outlining our heavy social calendar and the reason we were assembled.

“We would sit and talk but the end result was to be four five-minute presentations to the IOC Congress, delivered in English by athletes chosen only by us, with no external influence.

“The Finnish sailor Peter Tallberg, an IOC Member who was asked by Samaranch to be the liaison between the IOC Members and the invited athletes and to coordinate our activities, told us, ‘It’s now up to you!’

“Tallberg introduced Donna de Varona, the American dual gold medallist swimmer from Tokyo 1964 and a prominent broadcaster for ABC, who would provide useful guidance.

“With the formalities over, the wine glasses were filled. This was a time when the Olympic Movement was said to have no money and was struggling to find cities to host the Games. But it found plenty of wine, courtesy of Jurgen Schröder, the former German oarsman and our go-to person in charge of the athletes’ programme.

“The athletes were a convivial group, but all strangers. Each athlete from the East had an ‘interpreter’ in tow, although we later came to understand that these were their political watchers, there to make sure they toed the party line.

“It was obvious that many delegates at the Congress regarded us as a mere masquerade. This feeling was accentuated when we were joined by some of the members, national delegates, who sought to be seen with their star athletes.

“School visits, excursions, wining and dining – it was all a far cry from my rigorous training routine.

“When we got down to discussing what the four athlete speeches should focus on, what struck me was the fact that, regardless of sport, nation, or personal background, we soon found a united, common voice.

“The issues were multiple and complex. A burning question emerged: how, in four five-minute speeches, were we going to present all the topics that were important to us?

“Four short speeches would not be adequate. On the evening before the official opening of the Congress, on September 22, we drafted a letter which was delivered to President [Juan] Samaranch, asking for more time, and for a meeting with him.

“Early the next morning we had word that President Samaranch accepted our request to meet, and agreed to an additional five-minute presentation and a longer speech of 15 minutes on the last day of the Congress.

“Five main topics emerged – issues that had bitterly affected the athletes over the past decade and consequently questioned the perenniality of the Olympic movement.

“They were doping; amateurism; political involvement and boycotts; gender imbalance; and Olympic ceremonies – a topical subject for many athletes in Moscow who had seen the Olympic flag raised rather than their own national flag.

“Each topic touched a raw nerve. We had each been affected directly or indirectly by these five key points, with the boycott and systemic doping being the most significant news stories from the Moscow Games.”

“Although the social events had pulled some of our group away, those who remained wanted to seize this moment in the hope they could protect future generations of athletes from the harms we had suffered.

“We voiced our different experiences and challenged each other closely. Athletes were not trained nor were they encouraged to speak. The system discouraged such ‘political’ discussion and only a few realised that we needed to seize this moment and were prepared to do the work to meet the challenge.

“It became clear that while we wanted to ensure an East-West balance in our choices, we no longer needed the interpreters: those remaining all spoke good English, the language in which the speeches would be delivered.

“It was decided between us that there had to be unanimous agreement between all athletes for what would be finally presented. This in itself was quite extraordinary.

“We were between a Moscow boycott and a possible retaliation boycott in Los Angeles, in the middle of Cold War, yet we were a small group of athletes, none of whom had met two days prior, representing east and west, north and south, working together in a spirit of esprit de corps for the benefit of all athletes. It was truly refreshing. It was the Olympic spirit in action.”

The Moscow 1980 boycott, prompted by US President Jimmy Carter‘s decision to pull the American team in response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 (all the more ironic this year), saw more than 60 nations withdraw official representation at the Games. Some, such as Australians and British athletes competed without the blessing of their governments and many spent years without having their achievements recognised with national honours.

Writes Ford: “In Baden-Baden, the scars were still raw for those of us who had competed in Moscow, and even more so for those who had been prohibited from participating by their respective NOC [National Olympic Committee] or government.”

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser backed boycott but left it to athletes to decide whether to attend the Games or not. Ford had worked hard; she was among title favourites; she had raced at her first Games aged 14 and had got her first glimpse of the muscle and might of a GDR medals machine. In 1980, she felt she was upholding Olympic ideals by racing in Moscow.

Some called her “a traitor to this country”, words used in a letter she received and opened on the day of one of her races in Moscow. She writes: “How could someone write such a letter? The words hurt, the untruths. It was poison. What had we, the athletes, done to deserve this?”

“incentives”, called bribes by some, of Aus$6,000 (about €3,700) were offered by the Aussie government to athletes if they boycotted but as Ford tells me: “Politics and trade went on but sport was supposed to stop.”

In her autobiography, she writes:

“The boycott reinforced to us that the athletes played no part in the administration of sport. We were voiceless and we felt we were treated as insignificant pawns by a political machinery.

“Boycotts hurt athletes full stop, and have never achieved the political ends they promote.”

All of which and more was poured into her speech-writing in Baden-Baden. She notes:

“I had taken notes and written a speech on boycotts and their injustices: the indecision, the death threats and in my case, the Government offering financial rewards directly to athletes to withdraw from the 1980 team.”

“I felt it would be more powerful to have someone who had been excluded from the Olympic Games by a boycott present the speech, and turned to Kip Keino, who had missed the Montreal Games.”

Otzetova spoke on women’s participation; Bach, with his legal background, spoke on Rule 26, the amateur rule; Vladislav Tretiak, Soviet ice hockey goalkeeper, spoke on Olympic ceremonies; and Ivor Formo, the 1976 Norwegian Olympic cross-country champion, delivered an athletes’ plea for the IOC to take a tough stance against doping. In some respects, athletes are still waiting. For recalls:

“We all agreed that Sebastian Coe, a track gold medallist in Moscow, a native English speaker from Great Britain, would present the longer, final 15-minute speech on the last day of the Congress, his 25th birthday.”

That was this day 40 years ago.

“Every speech was a collective effort, the athletes’ united voice,” notes Ford.

“We said things that athletes weren’t allowed to say back then.”

For each speech, there was “a smattering of applause from the members” and the athletes decided they must demand action in the final flagship address, which would be heard on the last day of the Congress. Back at the bistro table that had become our meeting place, Thomas Bach, Seb Coe, Ivar Formo and I were the last to keep the flame alive. Every word was checked for clarity, to avoid misinterpretation, as we poured passion into our mission. Our deadline was 7am, one hour before the Congress reconvened.

“We raised the subject of life bans for dopers, of punishing coaches and members of the athlete entourage, and while we understood that a life ban might not be workable on legal grounds, it was clear that if we went in softly, nothing would change.

“On amateurism there was consensus: the athlete from the West was falling behind, tied to a more stringent interpretation of the amateur rule than in the Soviet Bloc, and athletes were struggling.

“It was time to relax this barbaric law that controlled the athlete, prohibiting them from financial gain. Rule 26 had to be changed to allow every athlete the same opportunity.

“Satisfied that the earlier speeches had made their mark, we deemed it important to reiterate our disappointment that the IOC had no women in its ranks and that female participation in less than 25 per cent of events at the Games was not good enough.

“It had to be said again that the IOC was ‘out of step’ and that male and female participation should be made equal at all levels.

“What about all those that had to forgo the opportunity to participate in the Games? Every athlete, we concluded, should have the right to compete without being subjected to political pressure or discrimination of any kind, and the Olympic Games must play host to the best athletes from all corners of the globe.

“We had been together for eight days, and although we did not know each other beforehand, a bond had developed, close friendships had formed, and respect for each other had grown.

“The four of us, it seemed, had each come to Baden-Baden with determination and hope that we could make a difference.

“And our overall message was that athletes should be involved in the IOC’s decision-making processes.”

“No discos – just discussion”, was one of the lines Coe read out to Congress and a leadership that had sent chauffeur-driven Mercedes to collect the athletes at the airport, men who had housed them in a fine hotel (but not quite as fine as the IOC hotel) and organised discos, city tours and other entertainment for athletes who had travelled to Baden-Baden for business not pleasure.

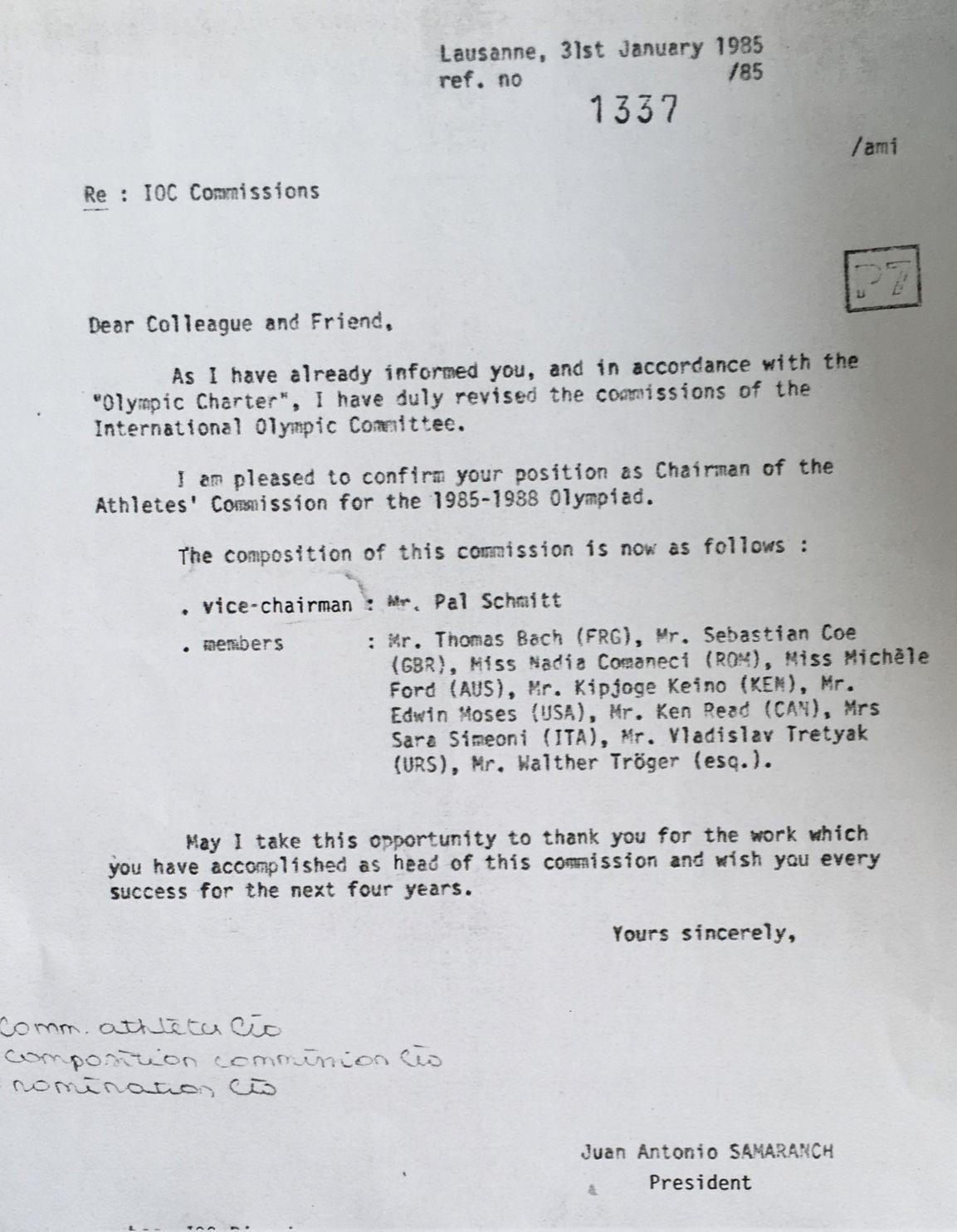

It would all end in the outcome shown in the letter below: the creation of an IOC Athletes Commission a month after the Congress and then reconfirmed in 1985, with Ford, Coe, Bach, Keino and Tretyak among the first members of the group that would take the athlete voice to Olympic bosses.

Ford notes that the speech delivered by Coe concluded:

“We strongly suggest that this group of athletes be regarded as the consulting body to help us attain the way in which athletes can participate in the decision-making processes of our movement.

“In his address, Peter Tallberg kindly referred to the athletes as a reserve – a hidden treasure. His inclusion into our group could be the key unlocking the trove.

“Finally, I feel that our inclusion in the Congress here in Baden-Baden and the tenacity with which we have grasped our tasks kills if not buries the common misconception that athletes are unthinking robots.”

In 2011, when Rogge delivered a speech about the Baden-Baden Congress, the IOC declared: “Of all the decisions that would alter the future direction of the Olympic Movement, none was more important than the establishment of the IOC Athletes’ Commission.”

The prospect and potential of that and the hopes and ambitions of Ford and other athletes who took their collective voice to Baden-Baden in 1981 is yet to be realised.

Michelle Ford-Eriksson MBE, was appointed to the IOC Athletes Commission in 1985 and had since held directorships at the Australian Sports Commission, Australian Sports Foundation, and Swimming Australia. A Director of Sport at the University and Ecole Polytechnique of Lausanne, Switzerland, in the 1990s, Ford-Eriksson worked with the Organising Committee for the home Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Her autobiography is a work in progress and is expected to be out in 2022