The Tale Of Tokyo & Hints Of A Change In An American Swim Season Of Plenty

An Olympic swim season like no other is well and truly behind us, the result book of the 32nd Olympiad sealed, the ripples from the Tale of Tokyo 202One on their way down the decades to come as part of the flow and lore of Games thrills and spills. Below is an editorial wrap of the swim meet, some of the key lines, analysis and commentary of an Olympic year delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, plus links to my reports of every final and a bit more.

This marks the start of a sabbatical from regular event coverage for me, Craig Lord, until other work is done. State of Swimming will still be here, with the occasional appearance of Ed and several guest posts in the months to come. Thanks to all those who read our work and engage with our efforts, including those that seek out the truth some would rather conceal. There’s work to be done. Here’s to a fine season ahead.

The northern summer wanes as its southern cousin stirs from slumber, the switch of seasons in nature a touch more inevitable and obvious than the subtle yet significant change of swim climate in an Olympic season delayed and shaped by the COVID pandemic.

As it turned out, this was not the year that the mighty United States succumbed to the next best thing to a superpower in the pool. Even so, Australian women, along with significant pressure asserted by Great Britain men and individuals that made Tokyo 2020ne a cause for celebration in Canada, China, Japan, Hungary, South Africa, Brazil, Germany, Tunisia and Team Tchaikovsky, all with at least one Olympic champion apiece, reminded us how fine the line is between dominance and disappointment, best or second best, gold or silver.

Let’s be clear: the United States won the swim meet – and that made it the eighth straight Games at which Americans have emerged from the Olympic pool victors with a decent margin over all other nations, the bulk of which decidedly belong to the vanquished when it comes to their ability to compete at the deep end of elite sport.

The USA topped the swim score not only because its men claimed the lion’s share of gold; its women fell significantly shy of their Aussie rivals on gold count but in the depth of minor spoils, they claimed more prizes than their male teammates. Indeed, the count was 15 out of 30 available silver and bronzes in solo events, including Open Water, where Americans took no prizes.

In terms of individuals, six American men took home a medal, compared to 10 American women who claimed half of all individual silvers and bronzes up for grabs in the biggest Olympic swim program in history.

With the addition of the women’s 1500m and men’s 800m freestyle and the 4x100m mixed medley, there were 37 events across nine days, compared to 34 events from Beijing 2008 and Rio 2016, after the introduction of the marathon, and 32 events held at all Games since 1996, when the women’s 4x200m freestyle joined the schedule.

Tokyo was the first Games at which men and women had precisely the same swim events to have a crack at. Had it not been for the new distance freestyle events, which extended the options for freestylers to six (three for ‘sprinters’, three for ‘distance’ crew, if you like) compared to two each for the other stroke specialists, Australia would have been level with the USA on gold count.

Of course, we must count all swim events, however old or new, the lost and reinstated in the mix. What we should avoid is the use of phrases such as “the greatest haul ever…” Or even “greatest since” – or worst since, for that matter, unless the percentages, not the numbers, stack up that way.

The schedule and program today cannot be compared to that of 1956, 1968, 1972, 1984, 1992, nor even 2016. If one swimmer had 2 targets and another 5; if one team had 37 targets and another 12, the resulting medal counts may lend themselves to the word “biggest” but not necessarily “greatest”.

Take the GOAT. Swimming is a sport that would have to introduce a whole new range of events before the measure of Michael Phelps could be written up as having been “matched”, you ,right imagine, and that very act of adding more events would mean that there could be no match unless were to compare a set number of solo and individual events relevant to the Phelpsian symphony, note for note, stroke for stroke, swim for swim.

Red threads, including the specific to the general, are more meaningful.

At 11 gold to the USA and 9 to Australia, we’re looking at a significant shift away from the kind of dominance Americans have come to expect of their swimmers over a 30-year period in which they have topped the medals table at every time of asking. Tokyo was the weakest American showing since Seoul 1988, the last Games at which the GDR’s State Plan 14:25 skewed any semblance of “Fair Play” at the heart of the way we measure success.

Questions and my answers might include:

- Were there cracks in the American armour? Yes

- Was pride challenged and dented? Yes

- Was the slide from outcomes at the previous five Games significant? Yes

- Are there issues with coaches and then connected to leadership culture? Yes (not surface; deeper understanding required)

- Was it a case of “another fine USA triumph”, as penned in some places? No

- Was it the great disappointment expressed and penned in some places? No

The USA – or certainly those within it with a competitive mind geared to sustaining competitive edge – will have been licking wounds and contemplating battle-scar tissue from the moment the medley relays were done on the morning of Sunday August 1.

The best of them will have done so in neither a maudlin nor triumphant spirit. Equilibrium and equanimity are key. With a slight sense of relief (the avoidance of defeat on gold count came down to the last weekend), the best of ’em will have been able to put a finger on “weakness” (relative) before it showed its face; they will also have set their minds to the alchemy of outcome to fuel required all the way to Paris 2024 in a challenged world that may be short on charging points and pit stops and time and heavy on the challenge of choice.

On right now, having started hot on the heels of the Games and the longest single cycle in Olympic history (barring the sum of those that never happened owing to war and boycott), is the International Swimming League, while December brings a World short-course Championships that may struggle to attract the best line-ups, caught as it is in between the need to rest and then refocus and the test of another season of cluttered calendars (Commonwealth Games, European Championships, World Championships among the challenges faced by individuals next year, with no word as yet about what the COVID shunt will mean for the flow in place since 2001 (year 1, Worlds; year 2, regionals; year 3, Worlds; year 4, Olympics … repeat).

In all of that, the ISL finds itself a little more lost than it ought to be. Not, of course with the teams and athletes and coaches and magnates taking part, not diehard fans. But, yes, lost in terms of its potential to grow swimming. How to do that if you fall into the niche and cracks of the rather closed affair season three’s openers have turned out to be.

There are several issues, among them a misunderstanding of where swimming “fits” in the grand scheme of things; how and why it covers sport and whether a model lends itself to being covered by the written media or whether it can be ticked off as “broadcast event – bypass”; what you need to consider if you want swimming to be “bigger”; how the media works, why the presence of the written media is significant and why it is almost entirely absent at the dawn of “pro-swim” in terms of any consistent coverage (league football, basketball etc etc all come hand in hand with an interest and following in the league, its teams and the progress of the season – and their audiences transcend the champion fan).

Then there’s subscription just to see the racing at a time when the pandemic has hit purses far and wide, private and corporate: that may work when it comes to kicking a pig skin up and down a field but is a truly hard sell when it comes to swimming, no matter how much fun, pay, points and passion are involved.

The governance and coaching jobs get more challenging (or perhaps in greater need of clear decisions about what to focus on; the Gandalfian “what to do with the time that is given us”) at a time when professional pay for performance demands a rethink of “how we do things”.

In terms of the Games just ended, the USA must contemplate those questions for what they are and where the sport is as well as in the context of traditions brought to a crashing end in Tokyo.

Relay Review

If there was weakness of an unusual kind in the ranks of the American team, it was in the place where its key rivals on the medals count – Australia and Great Britain – got stronger: relays. Both countries have made relays a great endeavour well beyond practicing takeovers. Go back to the days of Susie O’Neill and we find her talking of staying in constant touch with the sorority likely to make national relay line-ups, bonds built with the steel required for the blade in the battle come the hour. Go to Britain and hear them not just talk of their brotherhood but make it the bond that binds their passion for being the very best they can be at the very moment they must be.

You have to go back to Sydney 2000, when Ian Thorpe included 2 gold and 1 silver in his count of relay prizes to find an Olympics at which an American man was not the most decorated relay medallist in the pool at the Games.

In Tokyo, the man who topped the medals ranks in relays was … James Guy, of Great Britain, with a match of Thorpe’s two gold and a silver, albeit from a count of four relays available and a gold earned in the inaugural mixed event. Aussie ace Emma McKeon, at her third Games but first that delivered solo gold – and then in two events – was top woman, overall and relays.

In relays, the USA was not weak, just weaker than its been for decades relative to its rivals and, according to top man of the meet Caeleb Dressel, in need of being reminded that at their best, they are better than a world record, and therefore probably better than the rest.

Two missed podiums and the weakest relay action by a USA team forever and we arrive at a closing weekend in Tokyo with USA team director Lyndsay Mintenko (nee Benko) gathering Dressel and Co in her arms before they faced the last fight with GBR in the men’s 4x100m medley (and that two years after Britain felled the USA in that event at World titles). Had they not realised that they just needed to swim splits they had all proved themselves capable of before?

As it turned out, they didn’t need to even clock their best splits ever to win and break the World record, Britain, second in a European record, also facing the reality of a ninth day of action that left them nursing the sting of defeat but buoyed for the fight to come by the knowledge that at their best, they, too, had room for improvement of more than a second “just” to repeat the best splits they’d ever done. One day, it will happen and both the USA and Great Britain will race inside the World record, the finishing order down to the day and which team can fire on all four cylinders in the same race.

In Tokyo, the American medley men benefitted from a poor heat that placed them on the wing in a final that made the chase more difficult for Britain than it had been in Gwangju at 2019 World titles. The dynamic of races counts for much, as the USA was reminded in the 4x200m free and, all the more so, in the inaugural mixed medley, both won by Great Britain.

In the curtain-closing medley relays, the USA men withstood their strongest assault since it had taken a World record to keep Australia at bay in shiny suits at Beijing 2008 (2008, 0.70sec gap; 2021, 0.73sec; those two efforts the closest rivals have ever got to Americans that have often dominated with wins of 3 or more seconds) and Australia’s women send that same Mintenko message to their American rivals. Unless you’re all at your very best come the hour, we will beat you.

That’s the fine line the USA swim team has always understood. In Tokyo, it fell the wrong side of the line more often than it usually does.

If relays accounted for a key part in the puzzle, there was another significant shift in the character of American Olympic swim teams: the ability to produce swimmers in the ranks who step up beyond expectation and trials pace to make the medals, even gold, seems to have waned (the percentage of PBs and ‘better than trials’ efforts backs that up). And that just as other teams, Australia and Britain prime examples, have found more swimmers capable of the art of rising to the occasion.

Underpinning the aforementioned fine line are the following facts:

- The maximum number of medals any one swim team could have won in Tokyo was 67, overall, both genders, open water included: that’s 28 solo events, two per nation; two marathon races, two per nation possible at qualification stage); plus seven relays, three each for men and women, plus the new mixed medley challenge.

- Out of their 67 shots at the podium, USA swim teamsters delivered 30 medals, 11 of them gold, 9 silver, 8 bronze.

- That compares to this result at Rio 2016: out of 62 shots at the podium, the USA claimed 33 medals, including 16 gold, 8 silver and 9 bronze.

Percentage wise, that adds up to the following loss of form Rio 2016 to Tokyo 2021 in terms of team strength relative to the opposition:

- Gold count: 2016 – 16/34 = 47% 2021 – 11/37 = 29.7%

- All medals: 2016 – 33/62 = 53.2% 2021 – 30/67 = 44.7%

Not disastrous but the losses are significant, particularly because they buck a long-term trend and swim tradition:

- 2000 – Gold – 43.7% ; overall – 56.9%

- 2004 – Gold – 37.5% ; overall – 48.3%

- 2008 – Gold – 35.3% ; overall – 50.0%

- 2012 – Gold – 47.0% ; overall – 50.0%

- 2016 – Gold – 47.0% ; overall – 53.2%

- 2021 – Gold – 29.7% ; overall – 44.7%

“We got a really, really strong showing with a little less experienced team that we’ve had at the Olympic Games in the past,” according to Greg Meehan, the U.S. women’s head coach. There are reasons to agree with that (the 16 solo medallists from the USA were divided roughly into 8 with plenty of experience and big podiums to their name and 8 with less experience at the Olympic level) and reasons to debate its relevance, in so far as the same thought applied to many other teams, including, among others, Australia and Britain, which claimed gold in the 4x200m free boasting two swimmers on their Olympic debut, one of them just 18, when the downside of the American relay woe in Tokyo included poor performances from some of their more experienced team members.

Then there was Lilly King: bronze then silver, the third place in the 100m breaststroke behind Lydia Jacoby, an ‘inexperienced’ teen on her own team. Beyond the swim, King got a gold of her own that day for the way she handled the celebration of the new queen. Brava!

‘Experience’ is relative and a much a misused phrase: 11 gold medals were won in solo events in Tokyo by swimmers making their Olympic debuts, while Ledecky is part of a club of teens who made their breakthrough with gold in the cauldron of Olympic competition before ever having won any senior medals of significance before nor even raced in elite senior waters at global level.

The USA measures of men included:

- The 400m medley, the first final in Tokyo, produced the only podium with two American men in individual finals.

- American men topped the gold count for their gender, with 8 podium toppers, the relative weakness in their campaign, compared to previous Games, to be found in the measure of minor spoils: two silvers, two bronzes across all events.

- Caeleb Dressel was the American man who stacked up at every time of asking, in each swim he delivered, regardless of whether there was a medal in it for him. Those that did put him aloft the podium: 50m free, gold, Olympic record; 100m free, gold, Olympic record; 100m butterfly, gold, World record; 4x100m free, gold; 4x100m medley, gold, World record. Those five golds stacked up to the top man of the meet, the last gold in the medley relay including a glimpse of the “take that” pride and competitiveness at the heart of the engine of a beast of an athlete who achieved the gold standard, too, when it came to handling expectation, handling himself and paying respect to others, teammates and rivals.

- Dressel’s solo success represented the only swim triple in solo events.

- Dressel was one of three American men to make more than one solo-event podium, along with Bobby Finke and Ryan Murphy, while American women topped that tally of three, courtesy of Katie Ledecky, Hali Flickinger, Regan Smith and Lilly King.

- Bobby Finke’s victories in the inaugural 800m free and in the 1500m free made him the first American to claim a distance freestyle gold since 1984 (George DiCarlo, 400m; Mike O’Brien, 800m) and the first to claim two since 1976 (Brian Goodell, 400m, 1500m)

- American men lost a tradition when they missed the podium in the 4x200m freestyle relay, the result marking not only the first time the USA quartet had not claimed a medal in the long relay but the first time American men had missed the podium in any relay in Olympic history barring, of course, those occasions when they were absent, such as the boycott of Moscow 1980.

- The inaugural 4x100m mixed medley four days after the 4x200m free final marked the second time a relay featuring American men missed the Olympic podium.

- American men missed the podium in four solo events, including both breaststroke finals, the 200m butterfly and the 200m medley, criticism of Michael Andrew and whatever approach he took to his swim goals missing the bigger point and wider picture of the Team USA outcome: he was the best the USA had and no other American made the two individual finals in which Andrew was a medal shot (if he and his entourage got something wrong, they were the best of those who got something wrong, is another way of seeing it …).

Some Swim measures beyond the obvious, all nations:

- With Dressel as king, Australia’s Emma McKeon was the swim queen of the Games and most decorated swimmer overall, with a record seven medals, including gold in the 50 and 100m freestyle, both in Olympic records, and the 4x100m free (world record) and 4x100m medley relays; bronze in the 100m butterfly, 4x200m free and 4x100m mixed medley relay. The count of seven is a swim and all sports record among women, relying in part, of course, on the addition to the schedule of an extra relay.

- Just two individual titles that were retained, Adam Peaty’s dominant display in the 100m breaststroke making him the first British swimmer ever to keep an Olympic swimming crown on head and Katie Ledecky’s historic victory in the 800m freestyle granting her membership of the Triple Crown Club and the second American into that lounge alongside Michael Phelps, who joined founder member Dawn Fraser (Tokyo 1964, 100m free) and Krisztina Egerszegi (1996, 200m back) with victory in the 200m medley at London 2012.

- There were four doubles among women and three among men: McKeon (50, 100m free); Ariarne Titmus (AUS, 200, 400m free); Ledecky (800, 1500m free); You Ohashi (JPN, 200, 400m medley); and Dressel (50, 100m free; 100m ‘fly, the only triple, as mentioned), Finke (800, 1500m free) and Evgeny Rylov (Team Tchaikovsky, 100, 200m backstroke).

- The only solo Olympic swim champion from 2012 to make it back to the podium in 2021 was French sprint ace Florent Manaudou, who claimed silver in the 50m free five years after the same finishing place at Rio 2016, which followed gold at London 2012.

Most Medals

- Women: Emma McKeon (AUS) – four gold, 1 silver, two bronze – 7

- Men: Caeleb Dressel (USA) – five gold – 5

Most decorated relay swimmers:

- Women: Emma McKeon (AUS) – two gold, two bronze – 4

- Men: James Guy (GBR) – two gold, one silver – 3

National Firsts

Among pioneering swim moments in Tokyo were the following first golds in specific events for specific countries:

Women:

- Emma McKeon, in an Olympic record of 23.81 became the first Australian winner of the 50m free and the first to win it inside 24secs

- McKeon, in an Olympic and Oceania record of 51.96 became the first winner inside 52sec

- McKeon became the first Australian to claim the sprint double

- Katie Ledecky, in 8:12.57 for the USA, the first to claim the 800m freestyle title three times, and successively

- Ledecky, in 15:37.34 the first winner of the 1500m freestyle

- Ledecky became the first woman to claim the 800-1500 double

- Kaylee McKeown, in an Olympic record 57.47 the first Australian to win the 100m backstroke crown

- McKeown, in an Olympic record 2:04.68 the first Australian to win the 200m backstroke crown

- McKeon became the first Australian to claim the backstroke double

- Maggie Mac Neil, in an Americas record of 55.59 the first Canadian to win the 100m butterfly title

- Yui Ohashi, in 2:08.52 became the first Japanese woman to win the 200m medley

- Ohashi, in 4:32.08, became the first Japanese woman to win the 400m medley

- Ohashi became the first Japanese swimmer to claim the medley double

- Ana Marcela Cunha became the first Brazilian woman to claim Olympic swim gold with marathon victory over defending champion Sharon van Rouwendaal, of The Netherlands

Men:

- Tom Dean, in 1:44.22 the first British man ever to win the 200m freestyle title; his teammate Duncan Scott’s 1:44.26 for silver making the brace the first British 1-2 on freestyle since London 1908

- Ahmed Hafnaoui, in 3:43.36 the first Tunisian, African and Arab to win the 400m freestyle

- Bobby Finke, in 7:41.87 the first winner, for the USA, of the men’s 800m freestyle

- Finke became the first man to claim the 800-1500m double

- Evgeny Rylov, in a 51.98 European record the first Russian to claim the 100m backstroke title

- Rylov, in an Olympic record of 1:53.27, became the first Russian to claim the backstroke double

- Adam Peaty, in 57.37 over 100m breaststroke the first British swimmer to retain an Olympic crown

- Kristof Milak, in a 1:51.25 Olympic record the first Hungarian winner of the 200m butterfly. Milak left his long-time coach this week in favour of being guided by the mentor to fellow World 200m ‘fly champion Boglarka Kapas.

- Wang Shun, in a 1:55.00 Asian record the first Chinese man to win the 200m medley, the podium completed by Duncan Scott as the first Brit in the medals since 1984, and Jeremy Desplanches the first Swiss man ever to make the top 3 in the event

- Florian Wellbrock became the first German winner of the marathon with a dominant victory over Kristof Rasovszky, of Hungary, and European champion and 2016 1500m Olympic champion Gregorio Paltrinieri.

The Swim Speed Of Victory And Pace Of The Podium

There were many predictions of stunning speed at the Tokyo Olympic Games. Much of it felt far-fetched and more to do with the enthusiasm of the fan and blogger than the realities of preparation in a pandemic, delayed campaigns and the over-worldly nature of life at an Olympics like no other, including a lack of crowd, mandatory mask wearing, life in a bubble and all that came with it. I read predictions stretching to double-digit World-record stats and stuff like a 200m breaststroke podium all under 2:06. None got under 2:06 but the Olympic record took a tumble when Zac Stubblety-Cook claimed gold for Australia in 2:06.38, the first Dolphin win in the event since Ian O’Brien’s world-record triumph at 17 back in the same city at Tokyo 1964.

Reality is actually more thrilling than any impatience for speed ahead of its time, moment and circumstance.

Best be clear: Tokyo was not ‘slow’. Indeed the podiums stacked up like compared to Rio 2016:

- Men: faster wins and faster podiums in 10 of the finals, split seven solos, three relays

- Women: faster wins in 10 of the finals, split seven solos, three relays; faster podiums in 11 events, split 8 solo and 3 relays

And all-time:

- Men: 7 of the 16 comparable finals were won in the fastest winning time ever

- Women: 9 of the comparable finals were won in the fastest winning time ever

One stark feature of the Tokyo 2021 Games, albeit only in a number of events, was the ‘time-lapse’ speed in which titles were won. The starkest examples included:

- Men’s 400m free – Ahmed Hafnaoui’s 3:43.36 victory was a thriller that made history for Tunisia, marked the biggest upset in the event since 1956, Boiteau, his dad’s bonnet and all that … but also marked the slowest win since Atlanta 1996

- Men’s 400m medley – Chase Kalisz’s 4:09.42 victory was a nail biter in which the American broke free, set the pace and hung on for what was the slowest win since Sydney 2000

- Women’s 400m medley – Yui Ohashi’s 4:32.08 victory made her the toast of the host, her’s one of the most heartening tales of perseverance in the pool in Tokyo, the time on the clock marking the slowest win since Athens 2004.

None of which added up to anyone bowing their head: the history of those events above stands out for the outstanding nature, for a variety of reasons, of the pace-setters down the years, Ian Thorpe, Michael Phelps, Ryan Lochte, Ye Shiwen and Katinka Hosszu.

The Fine Line & Some of The Finest Lines:

I (along with others) wrote this kind of line on the eve of the Games : Katie Ledecky Vs Ariarne Titmus – The Heart Of USA Vs AUS Battle In The Tokyo Tank. And so it proved.

As stated, the United States had the edgiest and, in terms of gold count, weakest Olympic Games in the pool since 1988 and the last biggest of all gatherings before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the start of a new era – and relays played a big part in the drop.

If the Britain men’s 4x200m freestyle gold was won in magnificent style and at a place no USA team unassisted by suits has ever swum at, then Britain’s dominant World-record victory in the Mixed Medley relay confirmed the underlying message in that feature on the importance of a Ledecky to the USA’s ability to keep Australia at bay: not even the mighty assistance and multi-gold-winning capabilities of a Caeleb Dressel can be sure to keep the best of the rest at bay, even at a time

The presence of Michael Phelps and then he and Ledecky in Rio as the GOAT’s career came to a majestic close both highlighted the USA’s need for outstanding outliers and masked the vulnerability of the more mortal world-class swimmers that make up the bulk of its team and travel at a more worldly pace the best of the rest of the world sees and thinks “game on”.

Dressel stacked up very well indeed on the score of superhero, while the ranks of the USA swim squads named since Tokyo includes a healthy mixture of established veterans and newcomers. Most of the veterans may find Paris 2024 a stretch too far, even in terms of relays if the USA wants to be ahead of the next wave of ‘elsewhere’ building with a strong sense of “beatable America” in its balance of hope and realistic goal. Some of the newcomers look set to be forces to reckon with come their follow-up Games (or in some cases, their debuts in France should all go well) just three years away.

All of it looks like a finer line for the USA than it has been for a long time. We’re at a potential turn of swim history. If Australia and Britain and Canada and China keep rolling in the way they have been; if Japan recovers from the lost chances of a torn Olympic cycle; and if France builds back better from a Tokyo campaign that delivered just one medal but offered a glimpse of much better to come at a home Games … then the World No 1 swim nation will find the challenge ever tougher.

That’s a lot of ifs, of course. They come with another set of ‘ifs’ at home in the United States, such as:

- ‘if’ the things that have worked so well for the USA down the decades (college and its need to race tough in season while learning the meaning of ‘team’ and ‘dedication;’ and ‘discipline’ and much else, for example) continue to work in the way they have (not guaranteed);

- ‘if’ governance halts the obvious decline in influence of coaches at the decision-making table (the coach voice now is not what it was 5, more so 10, more so 20 years ago, for example – and that matters in key ways leadership figures appear to overlook in their search for an easier, well-paid and fairly comfortable political life in a sports realm due for a cultural shift, one led by changes in the law in the United States that place a needle on the skin of the autonomous bubble of Olympic governance);

- and ‘if’ the pro-swim era strikes the right balance between the need and will to earn and the need and will to work at a rate required to be competitive on what remains the biggest occasion in the sport, one that will remain so as long as representing a nation and bringing home the bacon for it continues to be a key ingredient of passion in Olympic sport.

The Swim Thrill In The Spill Of A Games Like No Other

The Games unfolded against a backdrop of protest in the host country, many citizens understandably concerned not only with the pandemic but the autonomic multi-billion-dollar cost of it all, the delay and then decisions to forgo ticket sales, return money where money was due back and make the Olympic Games the first in history to which spectators were not invited. Indeed, they were barred.

There may be a political cost to the Japanese Government when the country goes to the polls in a national election in November. The incumbent Prime Minister, Yoshihide Suga, has already announced that he will not stand for re-election.

The downside of the Games was not confined to matters unrelated to a bug, masks, feeding slots, isolation, quarantine, confinement corridors, daily tests, having to check in with security guards even if you wanted a coffee from the shop next door to your hotel and the numbing, costly and time-consuming bureaucracy that became a part of the 32nd Olympic experience.

There was also the continued Games colonialism of the broadcaster NBC in return for the dollars that feed many thousands of lifestyles among the sporting blazerati in the autonomous bubble of Olympic governance – there was an obvious upside. No-one asked the athletes and coaches, who, as ever, are not the priority of those who sign contracts that suit themselves better than the best interests of sports and their key stakeholders. Much is made of the return NBC has a right to expect on its investment. But what of the rights of hosts and their taxpayers? What of the rights of the Bank of Mum and Dad that is the biggest investor in Olympic sport – by far?

The Olympic sports economy is subsidised, which keeps the key protagonists in check not cheques, which is why the likes of the ISL is seen as a threat to the status quo, the pro-sports model acceptable if already established (basketball, tennis, golf, etc, all in the Games these days) but painted as somehow harmful to the best interests of sports in which athletes are asking for a fair share of the revenue from the show that would not be there without them.

Of late, I read a commentary penned by a manager, not writer, of a niche swim website. It talked of the days of amateurism as if they belonged to a golden era of sport; it talked about the dangers of professionalism and how that doesn’t fit the Olympic model and spirit. Not once did the writer stop to look in a mirror and ask: so, if we got no revenue for what we do, would we be here? Not once did the writer stop to ask: so, if the Olympic realm was not a humungous multi-billion-dollar industry, would it have survived? Not once was there any semblance of

The Olympic realm has many champions in one-eyed interest, while the best interests of athletes and those they work most closely with to provide us with the kind of spectacular sport we witnessed at the Tokyo Aquatics Centre in late July and early August play second-fiddle to the Dickensian masters sitting at their feast as orphans cry for more.

It needn’t be. There is a much better way – and a more affordable way, one that some within the Olympic sports movement get and work towards in ways that the system allows. The wheels of change, however, turn at the pace of one step forward, one giant hop, skip and jump backwards as those who have been given access to a lifelong lifestyle less ordinary and more lucrative resist the changes that might send them home to work harder for their keep, like athletes, coaches and others must do and do do, day in and day out on their swim quest.

The best thing about the decision to go ahead with the Games in Tokyo was clear: those who had worked for years to get to and perform at the Olympic level were able to be there and give it their best shot. Now that the results are in, that point ought no longer to be lost on anyone: not only did athletes get to have their moment and avoid the feeling of loss that afflicts those affected by boycott to this very day, for example, but the elite end of Olympic sports provided a ray of hope in a time of darkness and lost hope and will have helped rekindle the love of sport in many youngsters and motivate a good many of them to make it back to the swim, the run, the cycle and so on after a period in which regular exercise under professional supervision and in a team environment has been out of bounds and the doors of facilities locked.

The Top Treasure Hunters

Top of the Tokyo treasure hunters were Emma McKeon and Caeleb Dressel, the former tipped to do well but going beyond for her first two solo titles atop a record seven medals in all, the latter more than living up to his billing as the ‘new Phelps’, ‘the latest Spitz or Biondi’ etc by being himself, by writing his very own lines and name into the history books as a winner of five golds, two World-records victories and two Olympic-record victories in the mix.

Dressel – who survived ferocious swims from Aussie defender Kyle Chalmers to win 47.02 to 47.08 in a 100m free final from which they both merged heads held high; and from Kristof Milak in the 100 butterfly, a World record 49.45 required to keep a 49.68 European standards at bay from the swiftest 200m ‘flyer in history, a young Hungarian who left Tokyo talking about conquests and goals to come – confirmed what coaching gurus like Bill Sweetenham have long taught those willing to listen. As the Australian once said to me: “The Olympic Games is like no other environment in swimming … nothing comes close; you enter a cauldron and regardless of the form guide and what any swimming may be capable of, only those who can handle the environment emerge with gold round their neck”.

Hark Dressel, who turned the 50m free battle into a trouncing (his 21.07 over Florent Manaudou’s 21.55 represented the second-biggest gap between gold and silver in Tokyo relative to distance after the stunning 2.48sec by which Milak won the 200m butterfly … the American said in Tokyo against a backdrop of press conferences at which mention of ‘mental health’ was never too far away:

“I tried to convince myself that Worlds was the same, and it’s the same competition, but it’s a lot different here [at the Olympics]. It’s a different kind of pressure, and I’m aware of that now and I can stop lying to myself. It means something different. It only happens every four years for a reason, and it’s 20-something seconds or 40-something seconds. You have to be so perfect in that moment, especially if you have another year, a five-year buildup or a 24-year buildup, whatever you want to call it. There’s so much pressure on one moment. Your whole life boils down to one moment that can take 20 or 40 seconds. How crazy is that?”

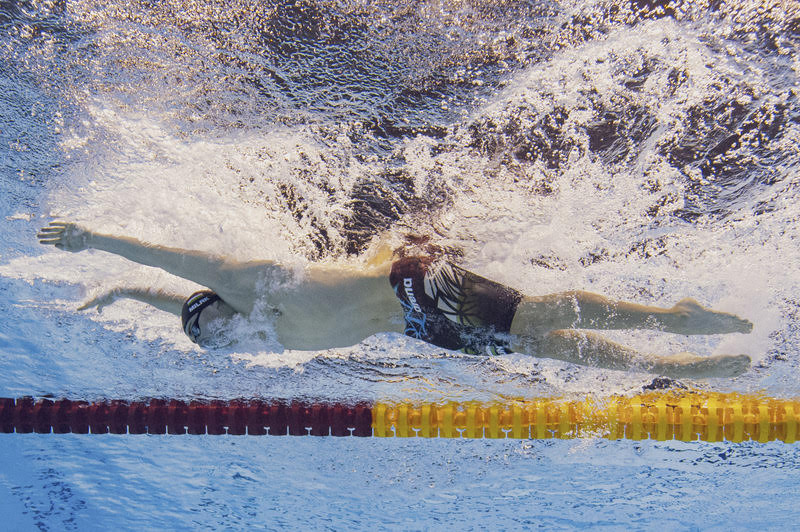

Caeleb Dressel – photo by Patrick B. Kraemer

The sentiment will surely have been reinforced by an appearance on ISL duty in Naples that attracted almost no mainstream publicity of late and, compared to the vast amounts of coverage of his Olympic glory should have reminded the League, the athletes and the sport of swimming, including those ploughing ahead with a World Cup series that creates not a single ripple in the vast ocean of world sport, that a great deal of work needs to be put into clearing out and cleaning up a competition calendar that contributes got the alienation of the wider audience out there waiting for meaningful engagement of the kind they sense, feel and sign up to when the glare of an Olympic Games tunes them in to the pool.

Where to start with that exercise of decluttering a chaotic calendar that even those who love swimming fail to fathom and end up showing no interest in? As Dressel states, “… it means something different”. So, make it the centre of the universe it has always been (while working to change the culture and governance structures of a movement that sometimes seems better suited to the 1930s than the 2020s).

Take the Games and build back, placing your World Championships and regional showcases where they fit and bringing the League on board as the full-cycle constant in a regular, condensed slot of its own that fans and the new fans in waiting can look forward to at the same time of year, year in and year out. Tennis, golf, F1, football … etc… think about it: they all have a home on the sporting calendar that comes around like the seasons, is expected, anticipated, covered and cherished.

Swimming, meanwhile, does not flow in the same orderly fashion. It’s as if a firm has been hired to dump a load of rubble in the stream with each passing year, COVID challenges and delays only serving to highlight and exacerbate the problem. The swim calendar needs revamping, the sport needs signposts that can be understood by any passer-by, not just the die-hard fan who delights at working out a puzzle that has nothing to do with how sports become popular beyond their own backyard (pool).

Fine Lines from the Swim Podiums

Women:

- Emma McKeon, Sarah Sjostrom, Pernille Blume, Siobhan Haughey and Cate Campbell: each of their stories was different, every one of them stacked with material worthy of a feature in its own right. Cate Campbell’s story has an edge on them all because of the outcome of Rio 2016 … five years on, there she was, on the 100m podium and bringing the Dolphins home to gold in World record time in the 4x100m free and gold in the 4x100m medley to close the meet. The slo-mo of her reaction at the last golden touch on the last day in the last race of the Games was a treasure to cherish and place on its own plight in the pantheon of her achievements.

- Sarah Sjostrom: silver in the dash represented a sensational prize just months after she broke her elbow in a fall on the ice back home in Sweden. That scuppered her chances of defending the 100m butterfly crown but the elbow injury had less impact on her sprint freestyle … and she made it count.

- Pernille Blume: a title lost but a hug from soon-to-be fiance Florent Manaudou added to a line about keeping success in the family. In 2012, when Manaudou claimed the 50m free title, he made himself and. Older sister Laure, the 2004 Olympic champ over 400m freestyle, the first solo-event gold medallist siblings ever in the Games pool. In Tokyo, it was silver for him (50 free) and bronze for his wife-to-be, who looks back on Rio to find the gold that completes the family set: brother, sister and sister-in-law-to-be now account for three gold, four silver and two bronze medals in the Olympic pool

- Ariarne Titmus: she did it. Felled the giant in the 400m and then wiped them all out in the 200m, both performances stellar not just in speed but in tactical approach and in the way she stuck to her own race plan while being aware of and resounding to the actual race underway, the moves of the great swimmer in the next lane. Titmus also took silver with a fine challenge over 800m but that’s where we turn to the extraordinary achievement of Katie Ledecky.

- Katie Ledecky: Imagine taking your first Olympic solo silver in a string of golds in your first race of the Games knowing that battle is among the most anticipated of the whole Olympics. Then imagine finishing 5th in your second defence of a crown on your way to final number three. It’s like being floored twice in the first two rounds and then being expected to get up and face the next 10 rounds in a pit at the centre of the known sporting universe, super troopers beaming down from the heavens like a sun in the desert. Ledecky got up, brushed herself down and took on the 1500m knowing it would not be her best ever. It wasn’t. It mattered not a jot. It was gold, the rains broke, the temperature cooled for the last of Ledecky’s battles at her third soaring Games. Technically, tactically, mind-over-matterly, she nailed it, Titmus’ terrific effort close but never making it feel as though the American was in serious danger. The 800m left just the 50m to go to complete a set of thrilling, story-line stacked women’s freestyle races.

- Kaylee McKeown. A sensational double with an emotional edge, McKeown dedicating her success to her late dad, Sholto, who passed away in August 2020 after a two-year battle with brain cancer. Kylie Masse was closest in both races for a Maple double delight backed up when she led the backstroke specialists in the closing 4x100m medley to help Canada to bronze. Emily Seebohm’s bronze in the 200m and heats swim in the 4x100m medley on the way to Australia claiming gold, McKeown on backstroke, wrote a great line in the swim history book: Seebohm made the podium at every Olympic Games 2008 to 2021, via 2012 and 2016. Four successive Games, three gold, three silver, one bronze, the 200m back completing the set of colours.

- Lydia Jacoby. Right time, right place, great swim – and all the way from Alaska. Hearts melted. Lilly King, defender, took bronze – and a gold for her gracious response: beaming smile on face she leapt across to Jacoby’s lane, raised the teenager’s arm with one hand and pointed at her with the other as if to say: ‘it’s passed – here’s the new champ’. Long live the old one and her attitude and outlook with it. It played a part in the next line, too …

- Tatjana Schoenmaker. 2:18.95, the one World-record win among women in solo events and part of a package of impressive swims and cool handling, round by round, from the South African 200m champion who’d taken silver in the 100m. King and teammate Annie Lazor followed and when the fight was over, they joined Schoenmaker and her teammate Kaylene Corbett in a huddle, a sorority of swim sisters celebrating the pure joy of the moment, the notion of rivalry left behind them in the wash of history.

- Maggie Mac Neil. What a great race, 0.13sec splitting all medals, the gold gone in an Americas record 55.59, 0.05sec ahead of Zhang Yufei of China. Mac Neil was also born in China. Her victory sparked an outcry in China’s domestic media and social media platform Weibo over the country’s now-scrapped one-child policy. As a baby, the Olympic champ-to-be was abandoned by her biological parents in February 2000. A year later she was adopted by a Canadian couple from London (Ontario) together with her younger sister. A new life in Canada led to the joyous moment we witnessed in Tokyo. The stuff of dreams that transcend the Olympic kind.

- Zhang Yufei: close in the 100m, she made the 200m her own, her win a world textile best the speed of which was concealed only by a 2:01 World record from a time of shiny suits. Victory was part of a collection of medals that made Zhang China’s No1 in Tokyo with two gold (200 ‘fly and 4×200 free) and two silver (100 ‘fly and 4x100m mixed medley)

- Yui Ohashi: medley double. A first for her, for Japan and in the depth a story of swim perseverance second to none at a home Games.

- 4x100m freestyle: Australia nailed it with a sledgehammer of 3:29.69 World record; Canada toppled the USA for silver – the first time the North Americans had ever finished in that order.

- 4x200m freestyle: China won through the even, consistent speed delivered by all four cylinders for a 7:40.33 World record; Ledecky was left with too much to do but a 1:53.76 split also got the Americans under the previous World mark; and Australia made it three under the elder mark with an Oceania record of 7:41.29 that, good as it was, left questions about coaching decisions that placed fastest first, slowest last and altered the dynamic of a potential win.

- 4x100m medley: a 3:51.60 Olympic record brought a fantastic Australian women’s team campaign to a close ahead 0.13sec ahead of a USA women’s team that took most podium prizes but succumbed to the Dolphins on gold count. In third, Canadian women completed a fine Tokyo campaign, Penny Oleksiak bringing business to a close an arm-swing shy of the Americans for her third medal of the Games, after silver in the 4×1§00m free and bronze in the 200m free, and her seventh Olympic career medal, after four podiums in Rio topped by victory in the 100m free.

Men:

- Not easy to win a dash race by the margin than might leave your rivals feeling better about themselves in a race of 200m upwards but at 21.07 Caeleb Dressel left the race of tight margins t the rest, Florent Manaudou and Bruno Fratus the sprinter left to celebrate being the closest to the class apart. Silver made Manaudou the second man in history to make three successive 50m Olympic podiums, the first having been Gary Hall Jr, with silver in 1996, shared gold with teammate Anthony Ervin in 2000, and then a gold of his own in 2004. Ervin was back in the final in 2012 and then, aged 35 in 2016, became the oldest Olympic swim champion ever when he reclaimed the 50m crown 16 years after he had first worn the prize at the age of 19.

- Kyle Chalmers. The teen Olympic champion of Rio 2016, he fell 0.06sec shy of retaining the crown in a ferocious battle with Caeleb Dressel that more than lived up to its billing as a battle of sprint giants.

- Tom Dean and Duncan Scott in the 200m freestyle, the first Brit 1-2 since 1908, Dean’s win a candidate for best Olympic debut alongside those listed below… the prize ultimately going to Kristof Milak, of Hungary.

- Ahmed Hafnaoui‘s lane 8 smoker of a 400m free – he struck from go and made hay while others were either away (defender Mack Horton) or shy of the best they had proved they could be. It was the slowest 400m win since Danyon Loader’s victory for New Zealand in 1996 but the way the Tunisian went about his business, length after length feeling like a new drive towards a goal that only he, perhaps, had believed possible before the claxon called them to the water, helped turn his historic first for Tunisia into one of the most memorable moments of the Games. I disagree with the notion that his was the breakthrough performance in the pool … anyone who follows French swimming will know that Hafnaoui did not “come from nowhere”, while the pace of his win tells us that it also relied on others missing their mark 21 years after an Australian called Ian Thorpe claimed gold at a home Games in Sydney in a World record of 3:40.59, aged 17.

- Bobby Finke – a distance double that the USA had waited almost 40 years for. Last-length fury was the theme … more on that if you click on the event coverage links below but suffice it to say that we had never seen the like … as our headline noted: Distance Double For Bobby Finke & The Fury Of Last-Lap Beyond Phelps, Scott, Biedermann & Zhang.

- Evgeny Rylov, the 100m backstroke champion by the smallest of winning margins over teammate Kliment Kolesnikov and then the double champion of his discipline with an Olympic-record win 0.7sec faster than the time in which he claimed bronze in Rio five years earlier. In the midst of controversy raised by defeated double defender Ryan Murphy, Rylov handled himself with composure and grace. Murphy, meanwhile, came in for some stick: he unleashed his feelings in the mixed zone straight after the 200m back swim and in word and timing it sounded for all the world as if Rylov was his target when it came to questioning the right of Russians to be in Tokyo because of their nation’s undoubted dabbling with doping and the crisis of the past seven years, including the deliberate obfuscation that landed Russia with a whole nation penalty for the second successive Olympic cycle. Murphy’s frustration may stem from things unseen and unreported but doing the rounds in the sport: in 2018, a swimmer who would become a member of the 2021 “ROC” Tokyo team was involved in a doping inquiry, one that led to no case being opened. That swimmer was not Rylov but in a sport where the cases of Sun Yang and Yulia Efimova belong to a catalogue of in transparency and different ‘deals’ for different swimmers barred for very similar misdemeanours, trust runs low, skepticism high.

- Adam Peaty – a case of imperfect conditions leaving him shy of what he is capable of on the clock but still sporting a title retained in one of the most dominant displays by a swimmer who has set a pace well ahead of the curve of his rivals, beyond even the dominance of Dressel and to a place that makes him the biggest pace revolution in breaststroke swimming in modern history by virtue of the fact that the gap between breaststroke speed and the pace of the World records over 100m on other strokes is, courtesy of the six times World champion, now significantly smaller than its ever been in history.

- Zac Stubblety-Cook – smart swim – one of the smartest performances of the week, in fact. Full stop.

- Kristof Milak – thunderous. At 1:51.25, his 200m butterfly victory was the biggest win of the week in Tokyo, making his the biggest Olympic debut among several candidates for that crown. It was backed up by a magnificent 100m of 49.68 adrift Dressel’s 49.45 World record. Think back to Rio 2016 and one might have imagined that Phelps’ 100 and 200m records might survive one cycle but were likely to be challenged in the not too distant … but both standards all but ripped to shreds? Surely not. And yet, they have been.

- Wang Shun and Duncan Scott – what a battle – and one of contrasting experience: for Wang it was big 200IM race Number Umpteen; for Scott, it was big race Number 2, 3 at most if you count the Commonwealth Games. More to come.

- Chase Kalisz held off Jay Litherland in the 400Im in a time that belonged to that club of time-lapse victories, a leap back before a time of Phelps required to find a win slower. Slower than heats, it was a fine battle nonetheless, Aussie Brendon Smith making hisOlympic debut shine with a podium prize.

- 4x100m free: The Americans stood tall: three 47s and a 46 split. Job done. Italy had four 47s and with that managed to keep Australia at bay despite a roaring 46.44 swim of the race from Kyle Chalmers.

- 4x200m free: Great Britain produced my choice of relay win of the week, their 6:58.58 a World textile record that dominated, Scott blazing home in 1:43.45.

- 4x100m medley: American pride took a pounding throughout the week but the closing relay and a World record of 3:26.78, Great Britain challenging on a European mark of 3:27.51, had all the stuff that makes swim racing gladiatorial and thrilling. A pity the quartets were not in adjoining lanes. Otherwise, a climax fitting for a phenomenal week of challenges overcome and hard work rolled out in spectacular fashion. Like the tradition of USA unbeaten record upheld, that medley relay duel and story will not end there …

Mixed:

- 4x100m medley: Great Britain plotted and planned and called in experts to calculate every conceivable variation of line-ups, home and abroad, to come up with “our best quartet”. That turned out to be the winning quartet immortalised in the history book as the first champions of the mixed medley: Kathleen Dawson, Adam Peaty, James Guy and Anna Hopkin. They set a World record of 3:37.58, China more than a second black, Australia a hand finger further adrift.

- For Guy, it was part of the best collection of relay medals in town: two gold (4x200m free) and a silver (4×100 men’s medley), a tally no other matched. Guy is the most decorated Britain team relay swimmer in history, his tally including: 5 Olympic podiums, six World-Championship podiums and ten European podiums since 2015, the year he claimed the World 200m freestyle title.

State of Swimming’s Tokyo 2020ne Finals & other coverage:

WOMEN:

W50fr – Emma McKeon 23.81 OR Gold Bolsters Best Olympic Campaign For Aussies; Sjöström & Blume Seal Podium

W100Fr – Emma McKeon Goes Solo To Gold In First Olympic Sub-52 (51.96) Ahead Of Siobhan Haughey & Cate Campbell

W200Fr – Ariarne Titmus Punches Green-&-Gold Double Ahead Of Haughey Hong Kong High

W400Fr: Ariarne Titmus The Terminator Pays Plaudits To Pioneer Pacesetter Katie Ledecky At The Changing of the Guard

W800Fr – Katie Ledecky Defeats Her Inner Balrog To Become Fourth Member Of Triple-Crown Club 8:12 To 8:13 Over Titmus

W1500mFr – Tears Of Joy & Relief As Katie Ledecky Punches Pioneering Mind-Over-Matter Gold In Gender-Parity Party In The Pool

Marathon – Brazil’s Ana Cunha Takes Marathon Gold Ahead of Defender Van Rouwendaal & Lee At The Third Time Of Asking Since 2008

W100Bk – Kaylee McKeown Rattles WR As Aussie Pioneer Champion In First Olympic Sub-58

W200bk – Kaylee McKeown Goes Back-To-Back Titles Ahead Of Masse As Seebohm Bows Out With A Bronze

W100Br – Alaskan Hearts Melt As Lydia Jacoby Takes The Crown From Rio Queen King, Schoenmaker In The Middle

W200br – Tatjana Schoenmaker Strikes African Gold In 2:18.95 World Record … King & Lazor Follow

W100 Butterfly – Maggie Mac Neil Flies To Canada’s First Olympic Butterfly Crown in 55.59

W200Fly: Zhang Yufei Takes Pace Of Four Lengths Fly Below 2:04 For First Time (No Shiny Buoy)

W200IM – Yui Ohashi At The Double As The Hero Of A Home Games In The Pool

W400IM – Yui Ohashi The Toast Of The Host Nation With First Japanese Long Medley Gold

Relays

W4x200Fr – China Lead Rush Under World Record Ahead Of USA & An Aussie Conundrum

MEN:

M50Fr – Caeleb Dressel Dashes To Gold No4 In 21.07 Olympic Record Ahead Of Manaudou & Fratus

M100Fr – Caeleb Dressel vs Kyle Chalmers To The American By 0.06sec

M200Fr – Tom Dean & Duncan Scott Deliver First Britain 1-2 Punch, Gold & Silver Split By 0.04sec

M400 Free – Ayoub Hafnaoui Delivers Biggest 8-Length Upset Since Boiteaux’s Dad & His Beret Jumped In At Helsinki 1952

M800Fr – Bobby Finke Fires A 26sec Stun Gun Past Three Favourites Down Last Lap Of First Olympic 16-Lengther In History

M1500fr – Distance Double For Bobby Finke & The Fury Of Last-Lap Beyond Phelps, Scott, Biedermann & Zhang

Marathon – Florian Wellbrock Crushes Rivals For Magnificent Mind-The-Gap Marathon Gold, A First For Germany

M100 Back – Evgeny Rylov 51.98ER Ends 29-Year American Bull Run As Kliment Kolesnikov Makes It A 1-2 For Team Tchaikovsky (& A Russian First … Shhhh)

M200bk – Evgeny Rylov Takes Down U.S. Bull Run With 1:53.29 OR Win Over Ryan Murphy & Luke Greenbank

Cold War Returns To The Olympic Pool As Murphy Unleashes Team Tchaikovsky Elephant In Room After Rylov Win

M100br – Adam Peaty Powers To 57.3 Triumph As First British Swimmer To Keep An Olympic Crown – Opens Valve On Emotions

M200br – Roo Zac Stubblety-Cook Boxes Clever On Way To 1st Aussie Title Since 1964 As Kamminga Takes 2nd Silver

M100 Butterfly – Caeleb Dressel Chased To 49.45 World Record By 49.68 Euro Mark As Krístof Mílak Makes It Two In Sub-50 Textile Club

M200 Butterfly – Kristof Milak Makes Magyar Swim History With Dominant 1:51.25 Olympic Record Victory

M200IM – Wang Shun Holds Off Scott & Desplanches With Puzzling Phelpsian Turn Of Speed

M400 Medley: When They Chased Chase Kalisz Down Only To Find He’d Done Enough For Olympic Gold on 4:09

Relays

USA 4×100 Medley Streak & GBR Ambition Live To Fight Another Day As Americans Go 3:26.78 WR

MIXED: inaugural 4x100m medley

Great Britain Throw Down Mixed medley 3:38.75 ER Gauntlet Just Shy Of China’s Global Mark

The Swim Song Of Unsung Heroes & A Glimpse Of Performance Culture Through The Stories Of GBR’s Golden 4×200 Relay

Tom Dean – Mum’s The Word On A Golden Double Built On Graft, Polish & World-Class Steer

The Guys and Gals Behind James, Biggest Hauler Of Great Britain Relay Honours In History

Post-Party Dancing

Tokyo Swim coverage Pre-Games:

Katie Ledecky Vs Ariarne Titmus – The Heart Of USA Va AUS Battle In The Tokyo Tank

What We Will Miss: Planet Phelps & The Pantheon Built By Bob & The GOAT 2000-2016

What We Won’t Miss: Sun Yang & An Entourage That Still Has Questions To Answer Over 2014 Doping Positive

Thanks for reading and sharing and liking and following our SOS coverage. In the coming months, we will run some guest posts from time to time during this author’s sabbatical from regular swim coverage.

Best wishes for a fine season and rest of year ahead – Craig – craig.lord@stateofswimming.com