Shane Gould & The Five-Medal Feat Never Matched In The 50 Years Since Her Olympic Epic At Munich 1972

Shane Gould claimed the first of three golds and five solo medals on this day 50 years ago in Munich at the 1972 Olympic Games, the feat of the “Goldfisch aus Australien” still unmatched to this day.

Michael Wenden, the double Olympic champion of 1968, summed it all up so well when he said:

“Shane was like a high-decibel concert that had such an impact, it left your ears ringing. But it left you still humming the tunes long after it came to an end”.

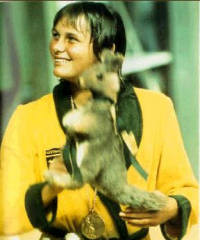

Mike Wenden. Image: Shane Gould in the Australia national-team suit of Munich 1972

How right he was.

Munich 1972 was also the Games at which Mark Spitz soared to a record seven golds, his tally including three relays. Gould raced in the 4x100m free relays in which Australia finished last in the final, while the Australians, Olympic championships in both the 4×100 free and medley today, did not reach the 4x100m medley final back in 1972.

Gould began her ascendancy across the Southern skies of Australia with an 8:58.1 world record over 800m freestyle. It was the first of 11 global standards that she would set over a period of two years and eight days that marked the greatest whirlwind career in swimming history, one topped by five individual medals at the Olympic Games in Munich, 1972. No female swimmer has matched that feat since, while Michael Phelps, with five solo golds among his eight victories at Beijing 2008, remains the only man to have reached five podiums in individual events at a single Olympics.

Shane Gould – A Shooting Star Bound For Olympic Immortality In Munich

Shane Elizabeth Gould was born in Sydney as the second daughter (after sister Lynette) of Shirley and Ron on the first day of racing (and the day after the Opening Ceremony) at the Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games, November 23. As Dawn Fraser arrived at the start of legend, so did Gould.

Fraser, Gould, Freddie Lane, Fanny Durack, the first female Olympic swimming champion, and Ian Thorpe were among the first Inductees Into the new Swimming Australia Hall Of Fame, the honour unveiled today at an Awards Ceremony in Sydney. Fraser and Gould were both there in person and received a a rousing reception.

Gould moved to Fiji with her family when 18 months old. By the time she was six, she was already a good swimmer developing a feel for water through fun and strength built climbing trees at the top end of an active childhood. She attended primary school at St. Peters Lutheran College, Brisbane, where a sporting house is named after her, and secondary school at Turramurra High School, Sydney, where a sporting house is also named after her and fellow Olympic champion from Munich 1972, Gail Neall (400m medley).

London in spring 1971 was the first we saw of Shane Gould, golden contender, outside Australia. It was Crystal Palace, Coca-Cola sponsored swimming in those days and Gould grabbed the headlines by equalling the standard of an Olympic legend: at 58.9sec over 100m freestyle, the 14-year-old drew level with the mark established by fellow Australian Dawn Fraser in 1964, the year she founded the triple Olympic crown club (100m freestyle, Olympic gold, 1956, 1960 and 1964).

Gould’s match marked the first of her 11 world records. She delivered it in a session that also saw teammate Karen Moras clock 4:22.6 to take down the 400m freestyle world record.

Two days later, Gould, coached at the Ryde programme of Forbes and Ursula Carlile, shaved 0.2sec off the 200m free world record that had stood to another triple Olympic champion, Debbie Meyer (USA, 200, 400, 800m free gold, Mexico 1968) at 2:06.7 since 1968.

- Forbes Carlile (3 June 1921 – 2 August 2016): A Personal Tribute From Shane Gould

- Australian Forbes Carlile Passes Away At 95: Swimming Mourns A Coaching Pioneer

In July 1971, at the Santa Clara meet in California, Gould cracked Moras’ standard over 400m with a 4:21.2 effort but she was not done yet. Back home in Sydney shortly after her 15th birthday, Gould became the first women to race inside 9mins over 800m, her 8:58.1 on December 3 a warm-up for an historic world mark 9 days later.

On December 12, 1972, Gould axed 19.3sec off the 1500m world mark that had stood to Meyer since 1969, the Australian’s 17:00.6 making her the first women in the modern era to hold all world freestyle marks from 100m to 1500m simultaneously. The only other woman to have achieved that was American Helene Madison (1931-33); she and Gould are the only others and in prevailing context are likely to remain so for the rest of time, the likelihood of a Sarah Sjostrom or Emma McKeon and a Katie Ledecky getting the better of each other at the extremes of the distance spectrum remote to say the very least.

Several months later at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, Gould – dubbed “Die Goldfisch Aus Australien” by the German media and the focus of a US women’s team that took to wearing t-shirts sporting the words “All that Glitters (sic) is not Gould”.

Strength in numbers. How to deal with that? Gould sat down and thought about it before hitting on the move that would make the call room a little easier for her and a little more troubling for the rest. Years later, Gould told me: “I didn’t want to have to keep looking them all in the eyes so I took my nail file along with me so that I could be distracted by sharpening my nails while we were waiting.” Sort of Shere Gould, an aquatic Khan to be wary of.

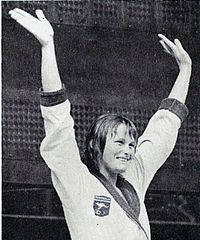

It all worked out rather well. Gould claimed three gold (200m, 400m free, 200m medley, all in world-record times, of 2:03.56, 4:19.04 and 2:23.07 respectively), a silver (800m free) and a bronze (100m free), a five-solo-medals tally at a single Games that has never been surpassed among women in Olympic waters. Gould remains the most successful Australian swimmer ever at a single Games in solo racing.

In February 1973, Gould became the first women to race below 17mins over 1500m with a 16:56.90 world record in Adelaide. That, as things turned out, would be her last entry in the elite record books. Soon after, she opted out of the fast lane just as the first World Championships loomed together with a woeful era of systematic doping and almost two decades of dominance by GDR women.

Beyond the ebb and flow of years that included motherhood and four children, Gould was to be found back in the swim towards the end of the 90s, and in April 2003, swimming in the 45-49 year bracket, she set a world masters record of 2.38.13 over 200m medley.

The 1990s brought a resurgence of recognition for Gould: the Olympic Order was awarded to her in 1994, a year later she was officially recognised as a “Legend of Australian Sport”, and three years on was granted the title of “Living National Treasure”. In 2000 she was as Olympic Torch Bearer at the Opening Ceremony for the Olympic Games in Sydney.

Gould tells her story in her own words in her autobiography, Tumble Turns.

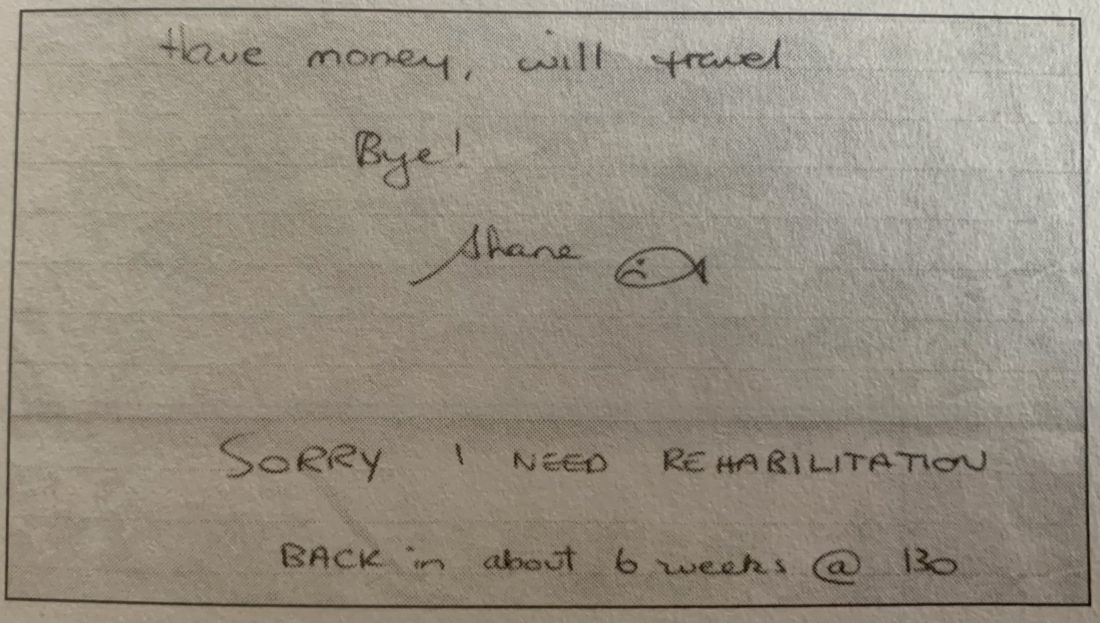

In 1973, keen to find out who she was and wanted to be, Gould left the note to the right (courtesy of Shane Gould, Tumble Turns) for her parents. She would not return to elite-level swimming in her youth. On the trail of life, she married Neil Innes at 18, became a Christian, and lived on a working farm near Margaret River in Western Australia’s South West, developing fine horsemanship skills along the way. Gould farmed and taught horse-riding and surfing. The couple have four children and three grandchildren. Shane’s marriage to Innes ended after 22 years, coinciding with a return to public life. In 2007 she married Milton Nelms, ‘the water whisperer’, and the couple spend much of their time in Tasmania when not travelling to promote water safety, swimming as a life-saving and enhancing skill and working with the Swedish Center For Aquatic Research, organisers of the World Aquatics Development Conference. More at the Shane Gould website.

The honours have spilled beyond the pool and sport: in 2003, Gould received the Centenary Medal for Contribution to Australian Society and in 2006 was inducted into International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame. Her honours also include: Best Sportswoman in the World (1971); ABC Sportswoman of the Year (1971); ABC Sportswoman of the Year (1972); Australian of the Year (1972); Member of the Order of the British Empire (1981); Sport Australia Hall of Fame (1985); Olympic Order (1994); Olympic Torch bearer (2000) Australian Sports Medal (2000); Centenary Medal (2001); and Gould is recognised as an official “Australian National Living Treasure”. There was also this: In 1993, the State Transit Authority named a RiverCat ferry after Gould.

Among other projects that Gould is involved in these days are the Fiji Swims; her own foundation; patronage of the Devil Island Project building free range extensive enclosures for the endangered Tasmanian Devil in Bicheno on the east coast of Tasmania); while she is a key supporter for marine education and a campaign to create more aquatic reserves around the coast of Tasmania.

In 2018, Gould won the fifth season of Australian Survivor, becoming the oldest winner of any Survivor franchise. By then, she had graduated with a Masters in Environmental Management, with a Human Geography focus, from the University of Tasmania, just a part of a lifetime of learning that culminated in her becoming Dr. Shane Gould. Like her medals and records, it wasn’t a case of ‘honorary’ but earned through study and academic achievement.

On this day 50 years ago, Gould claimed the first of her three Olympic gold medals, each of them coupled to a World record: the first prize, as a pioneer of pace over 200m medley in Munich, showed the versatility of the Australian with a heightened sense of ‘feel’ for water. Here’s how the eight days of racing at the 1972 Olympic Games granted Gould sporting immortality:

Day By Day To A Date With Olympic Immortality

Day 1: 200m Medley

The heats passed with no-one surpassing the Olympic record of 2:24.7 set by American Claudia Kolb for gold in 1968 (Kolb’s World record stood at 2:23.5, from Olympic trials in 1968). Gould qualified for the final out in lane two; an outside chance, a good warm-up for her freestyle events, perhaps? Gould was more versatile than many had yet come to appreciate.

200m Individual Medley Date: August 28, 1972 Athletes: 44 Nations: 26

1 AUS 2:23.07wr Shane Gould

2 GDR 2:23.59 Kornelia Ender

3 USA 2:24.06 Lynn Vidali

4 USA 2:24.55 Jennifer Bartz

5 CAN 2:24.83 Leslie Cliff

6 GDR 2:25.90 Evelyn Stolze

7 JPN 2:26.35 Yoshimi Nishigawa

8 USA 2:27.42 Carolyn Wood

In the final, Gould and Lynn Vidali (USA), the fastest qualifier, turned together ‘fly to back on 31.07, with 13-year-old Kornelia Ender (GDR) on 31.45. Vidali took command of the race on backstroke, turning in 1:06.74, followed by Ender, 1:07.60, and Gould, 1:08.46. The Australian edged back into golden contention on breaststroke, Vidali’s lead cut to 1:07sec over Gould as she turned in 1:50.00, the Australian on 1:51.07, Ender now fourth on 1:52.03 behind Jennifer Bartz (USA), on 1:51.27.

The young East German teenager destined for spectacular progress 1973-1976 then put in an extraordinary split of 31.56 on freestyle but Gould’s 32.00sec finish for the World record of 2:23.07 was enough for the first of her three golds. Ender claimed silver in a European record, 0.52sec behind the champion, while Vidali hung on for bronze ahead of Bartz.

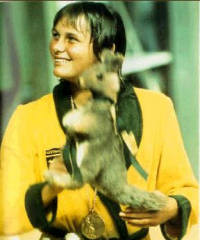

On the way to the podium, Gould had a toy kangaroo thrust in her hands by a celebrating Dawn Fraser. The images that followed were among the most iconic of Munich 1972.

Six months after the Games, Ender set a world record of 2:23.01 at the start of a phenomenal run on the world record books. An extraordinary talent before doctors and coaches in the GDR started to administer steroids to athletes under State Plan 14:25, a government-led doping programme, Ender would most likely have won medals off her own steam but it is unlikely that she would have been so dominant.

Her four gold medals in Montreal 1976 might have been five but for the fact that the 200m medley was dropped from the Olympic programme in 1976 and 1980. On June 5, 1976, Ender set a world record of 2:17.14. In Munich, her last 50m of the 200m medley suggested that she might have been a medal, even title, contender in the 100m freestyle but two others had been selected and the full might of the GDR medals machine was yet to take flight.

Day 2 – 100m Freestyle

In Munich, Shane Gould raced 4.2km in 12 races over eight days. Her coaches, Forbes and Ursula Carlile, believed she could handle the pressure and workload. Head coach Don Talbot, however, recommended that she shed the 800m from her programme. Forbes Carlile would not hear of it, while Australian team selectors added Ursula to the two-person coaching staff for the specific purpose of looking after the prodigy.

On the same day she raced 200m medley heats and final for a first gold and World record, the Australian swam heats and semi-finals of the 100m free. In the third heat, Dawn Fraser’s 59.5 Olympic record was improved 0.03sec by Magdolna Patoh (HUN). Three heats later, Gould clocked 59.44. In the evening semis, Shirley Babashoff (USA) improved the mark to a 59.05, with Gould taking the second semi in 59.20.

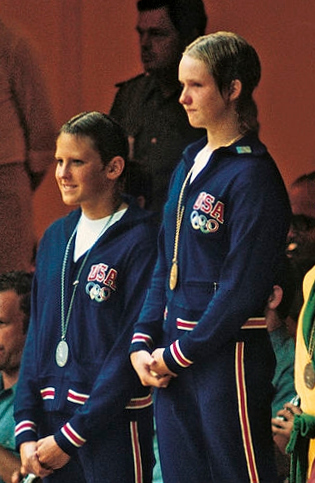

100m Freestyle Date: August 29, 1972 Athletes: 46 Nations: 23

1 Sandra Neilson USA 58.59or

2 Shirley Babashoff USA 59.02

3 Shane Gould AUS 59.06

4 GDR 59.21 Gabriele Wetzko

5 FRG 59.73 Heidemarie Reineck

6 GDR 59.91 Andrea Eife

7 HUN 1:00.02 Magdolna Patoh

8 NED 1:00.09 Enith Brigitha

In the final, the signal sounded but Babashoff got left on her blocks. Teammate Sandy Neilson was the pure sprinter in the field and turned first in 28.46, with Enith Brigitha (NED) second in 28.71 and a pack of four, including Gould, following within 0.25sec. Babashoff was still trying to make up for her poor start, on 29.12, with Gabriele Wetzko (GDR) last in 29.18.

Neilson could not be caught on the way home and took the crown in 58.59, just 0.09sec shy of Gould’s world record. The Australian looked as though she would take silver until the closing five metres, when Babashoff roared home. The scoreboard confirmed that the American had clinched silver in 59.02, 0.04sec ahead of Gould, with Wetzko having made up ground in similar fashion to Babashoff, for fourth place in 59.21.

The top two, both schoolgirls from Southern California, had very different fates after the Games. Neilson did not make it to Montreal four years on, while Babashoff claimed silver medals behind the first East German products of State Research Plan 14:25. The American might well have been the most decorated female swimmer in history in 1976 but she returned home with one gold, gained in what is arguably the greatest American relay swim ever witnessed, ahead of the GDR in the 4x100m freestyle.

The fight for Olympic acknowledgement, recognition and reconciliation for the sporting crime of the century goes on: it unfolded on IOC watch, the IOC’s accredited laboratory was at the heart of the deception and its secrets but Olympic bosses continue to turn a wilful blind eye to the damage done to women’s sport and the Olympic Movement to this day.

After Montreal, Babashoff quit swimming, while Neilson went on to race as a master in the 1980s and swam inside the minute in her 40s.

Day 3 – 400m Freestyle

The Olympic record fell in the first and fourth heats of the 400m freestyle: first to Jenny Wylie (USA) in 4:27.53, then to Novella Calligaris (ITA) in 4:24.14. Gould progressed in fifth, on 4:28.46, with Shirley Babashoff (USA) last through, on 4:31.98. They would all pick up the pace in the final but only one would move the clock below the 4:20 mark for the first time.

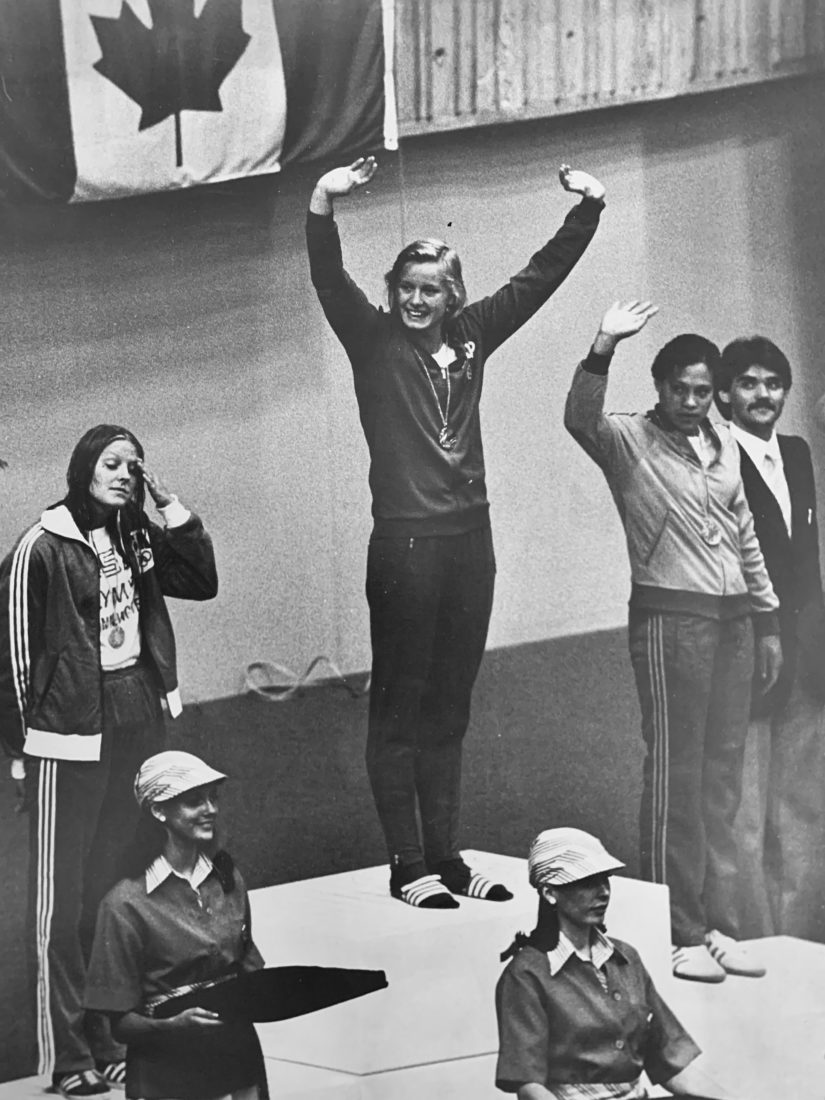

400m Freestyle Date: August 30, 1972 Athletes: 29 Nations: 17

1 AUS 4:19.04wr Shane Gould

2 ITA 4:22.44 Novella Calligaris

3 GDR 4:23.11 Gudrun Wegner

4 USA 4:23.59 Shirley Babashoff

5 USA 4:24.07 Jenny Wylie

6 USA 4:24.22 Keena Rothhammer

7 NED 4:29.70 Hansje Bunschoten

8 NED 4:31.51 Anke Rijnders

In the final, Gould roared away from her rivals from the outset, turning first in 1:01.50, 2:07.04 (1:05.54) and 3:13.55 (1:06.51) before claiming the crown in 4:19.04 (1:05.49), a world record and the first sub-4:20 effort.

The silver went to Calligaris, on 4:22.44, a European record, and bronze to Gudrun Wegner (GDR) ahead of Babashoff, while Keena Rothhammer (USA), who had tried to stay as close to Gould as she could until halfway, with splits of 1:02.57 and 2:08.97, found the pace too hard and faded to sixth. She would have her moment come the 800m.

Day 5 – 200m Freestyle

In heats of the 200m, the Olympic record fell three times, to Americans Ann Marshall, in 2:08.12, and Keena Rothhammer, in 2:07.48, and then to Andrea Eife (GDR) in 2:07.05. The World record had been set at 2:05.21 by Shirley Babashoff at U.S. Olympic Trials. All medal winners would race inside that in the final.

200m Freestyle Date: September 1, 1972 Athletes: 33 Nations: 17

1 AUS 2:03.56wr Shane Gould

2 USA 2:04.33 Shirley Babashoff

3 USA 2:04.92 Keena Rothhammer

4 USA 2:05.45 Ann Marshall

5 GDR 2:06.27 Andrea Eife

6 NED 2:08.40 Hansje Bunschoten

7 NED 2:09.41 Anke Rijnders

8 GDR 2:11.70 Karin Tuelling

Gould set a pace that rivals struggled with, turning first at the 50m and 100m in 29.23 and 1:00.04 (only 0.04sec slower than the time in which the solo 100m title had been won in 1968). Rothhammer and Babashoff, the third American in the final to have turned up in a t-shirt declaring “All that Glitters is Not Gould”, went through in 1:01.41 and 1:01.44, Marshall on 1:01.45 and Eife on 1:01.75.

By the last turn, Gould, on 1:32.39, still had a lead of 0.90sec over Rothhammer and 0.91sec over Babashoff. Down the last length Babashoff swam the fastest split, of 31.03, but a 31.27 from Gould delivered a third gold and a third world record, in 2:03.56. Babashoff fell 0.77sec shy but claimed silver ahead of Rothhammer, Marshall within a stroke of her teammates just off the podium.

Day 7 – 800m Freestyle

By the time Shane Gould rose to her blocks for the final of the 800m freestyle in Munich, she had raced a total distance of 3.4km, won three gold medals in World-record times, in the 200m and 400m freestyle and the 200m medley, and claimed bronze in the 100m freestyle. Her performance had come close to proving USA team t-shirts wrong: “All that Glitters Is Not Gould”. Keena Rothhammer (USA) had also had a busy week, finishing sixth in the 400m and third in the 200m, behind Gould, the champion, in both races.

In the 800m heats, Novella Calligaris (ITA), silver medallist in the 400m, set an Olympic record of 9:02.96. In the next heat, Rothhammer clocked 8:59.69. Gould and Jo Harshberger (USA), who had set a world record of 8:53.83 at USA trials, were also through to the final.

800m Freestyle Date: September 3, 1972 Athletes: 36 Nations: 19

1 Keena Rothhammer USA 8:53.68wr

2 Shane Gould AUS 8:56.39

3 Novella Calligaris ITA 8:57.46

4 Ann Simmons USA 8:57.62

5 Gudrun Wegner GDR 8:58.89

6 Jo Ann Harshberger USA 9:01.21

7 Hansje Bunschoten NED 9:16.69

8 Narelle Moras AUS 9:19.06

In the final the day after heats, Calligaris led the way at 100m, on 1:04.15, with Gould and her three American shadows, Harshberger, Ann Simmons and Rothhammer within 0.4sec of each other. At 200m, the Italian was still ahead, on 2:11.01, Gould on 2:11.66, with Rothhammer the last of the Americans through, in 2:12.72. Calligaris led at 300m on 3:18.65, Gould on 3:19.18, with Simmons and Rothhammer also below 3:20 and Harshberger 0.19sec the wrong side of the mark and starting to show signs of struggling.

By 400m, the pressure was building, Calligaris turning in 4:26.67, Simmons on 4:27.28, Gould on 4:27.34, Rotthammer on 4:27.41, and Gudrun Wegner (GDR) starting to make a move, on 4:27.90. It was then that Rothhammer shifted gear. In the next 100m, she drew level with the leader, Calligaris turning 0.05sec ahead of the American at 500m, on 5:34.51. Gould was just 0.79sec away and Simmons a further 0.33sec adrift, Wegner 0.1sec behind her.

Rothhammer maintained her increased pace as the pack began to feel the pain. By 600m, she was the clear leader, on 6:40.58, Calligaris hanging on ahead of the rest in 6:42.22, 0.29sec ahead of Gould, with Simmons and Wegner almost a second off that pace. The order in which they turned with 100m to go would not alter, Rothhammer on 7:47.04 to Gould’s 7:50.25 and Calligaris 0.08sec back. With a final 100m of 1:06.64, Rothhammer claimed the crown in a world record of 8:53.68. Gould had little trouble taking silver, the 100m world record holder stroking out the fastest homecoming split, of 1:06.14, ahead of Calligaris, who held off a fast finish from Simmons to take bronze by 0.16sec.

All eight finalists had raced their first and last Olympic 800m final. In 1973, Gould, 16, announced her retirement and never made the inaugural World Championships, at which Calligaris claimed the 800m crown ahead of Harshberger and Wegner, while Rothhammer won the 200m crown and finished second in the 400m, with Calligaris third.

Tribute To Forbes Carlile

Gould’s coach Forbes Carlile passed away aged 95 on the eve of racing sat the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. At the SwimVortex website that was forced to close because of a FINA campaign to “discredit” its work, Shane penned a moving tribute to Forbes, in which she concluded:

“I am grateful to have had the opportunity to know him, be the beneficiary of his knowledge, admire his advocacy for coaches, drug free swimming, daily school physical education and other campaigns. His curiosity about how people could perform in water, with a guileless approach, made him a very interesting person and I will miss him.”

Shane Gould – image, Forbes Carlile, courtesy of Forbes

Our SOS 50th anniversary trip down memory lane to Munich 1972:

- Mark Spitz & The 50th Anniversary Of Seven Golden Masterstrokes To Olympic Immortality

- When Roland Matthes, ‘Rolls Royce Of Backstroke’, Cruised Towards An Olympic Double-Double Never Repeated In 50 Years Since Munich 1972

- When Gunnar Larsson Got Gold 4:31.981 To 4:31.983 Over Tim McKee In Munich 400 Medley That Stopped Swim Clock At 0.01 For Next 50 Years

- Golden World-Record Wins For Karen Moe & Gail Neall In Munich 50 Years Ago This Day

- When Brad Cooper Got Gold & Rick DeMont Paid A Price For The Failures Of U.S. Officials

- When Melissa Belote Bagged Three Backstroke Golds At Munich 1972 – The 1st Won This Day 50 Years Ago

- The Legend, The Lore, The Hidden Tragedy In American Olympic 4×100 Medley Gold This Day 50 Years Ago At Munich 1972

- Iron Mike Burton & The Historic Defence Of The Olympic 1500m Free Crown As Swimming Ended At Munich 1972 This Day 50 Years Ago