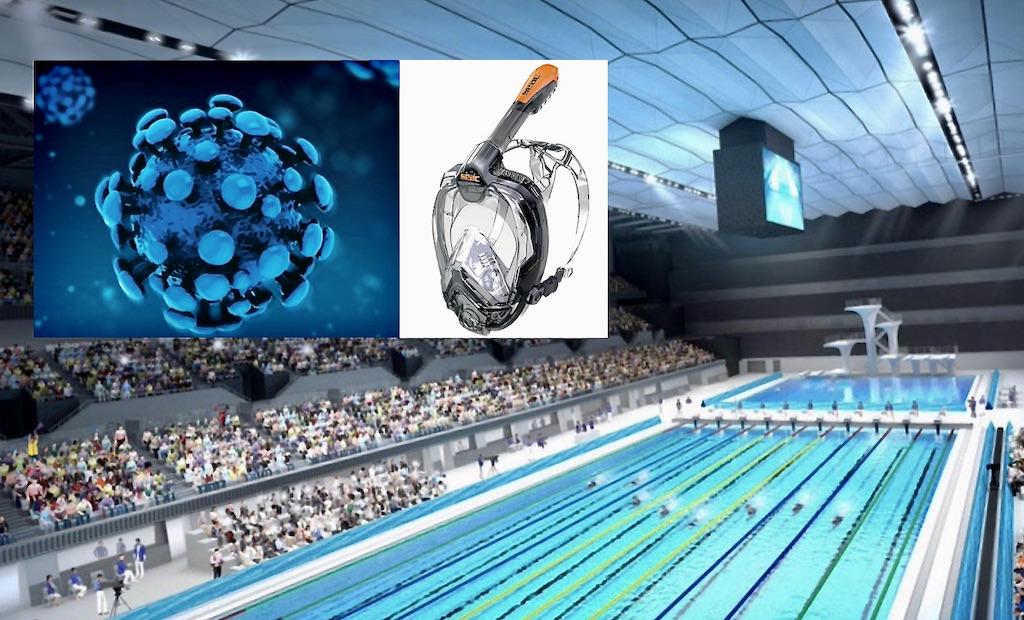

Olympic Swimmers ‘Must’ Wear Full-Face Scuba Mask & Snorkel In Tokyo 2020 Warm-Up Pool To Mitigate Covid Risks

In an Olympic first and sign of the times in a global pandemic, swimmers are to be asked to wear full-face scuba mask and snorkel during warm-up and swim-down at the Covid-delayed Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games to mitigate the risk of coronavirus infection.

Worried over the implications for athletes, sources close to FINA have unmasked a confidential version of the “Technical Playbook” issued by the Tokyo organising committee, to National Olympic Committees and the international regulator for swimming.

Among additional instructions in the Technical Playbook for all swimming teams bound for Tokyo for the Games that get underway on July 23 is a requirement for “every swimmer to be provided with a full-face scuba mask”. Moreover, each athlete will be “responsible for the care and cleaning of the equipment to ensure safety for all at all times.”

The Playbook is one of several such documents that have been issued by organisers, including one that tells audiences in venues to Clap But Don’t Sing as a way of containing the risk of virus spread.

One leading coach contacted by SOS said he hoped the full-face scuba mask would not be a requirement in Tokyo, adding: “Look, it’s April 1 and we’ve got nearly four months to sort this out. We’re talking to others teams and we’ll be trying to cut this off at the pass. We don’t think it’s necessary, nor practical and we don’t want not affecting performances.”

NB: The day now long – the reference to April 1 in the quote above gives the game away … so, for the record – April Fools 🙂

According to concerned sources who point to the fact that chlorine kills coronavirus and treated pools are among the safest environments, organisers ask for understanding and compliance with the new and “unusual but necessary” rule. An explanatory note in the Playbook states:

“We asked ourselves if a full-face scuba mask and snorkel would alleviate the concerns we have about the numbers of athletes who will warm up in the main competition pool and the preparation pool. Would masks help slow the spread of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19? We concluded ‘Yes’. Full face mask and snorkel, combined with other preventive measures, such as frequent hand-washing and physical distancing, lane control and following general equipment hygiene protocol can would offer an extra layer of protection for swimmers in the same way that N95 masks will for all attending the Games.”

One source, a performance director for a leading swimming nation who preferred not to be named, told SOS: “This sounds like a step too far. The swimmers will be tested regularly, will be living in bubbles; many will have been fully vaccinated; and lane controls will be in place. Those are the same sorts of protocols as we’ve been operating for our squads during the past year, without a single infection. We’re talking thousands of swims over many months.” The source added:

“Warm-up and swim down are important parts of the performance picture. Swimmers should not be asked to put on equipment that might impact their swimming and ask them to swim with a technique they’re not used to right on the edge of Olympic racing. I’ve talked to a few colleagues around the world and we all think this goes too far and should be stopped.”

The Playbook provides scant instruction when it comes to the technical specification of masks that would be required. Moreover, there are no details when it comes to who would supply a full-face scuba mask and snorkel for each of the 800-plus swimmers expected in Tokyo for the Games.

In 2009 at the Rome World Championships at the height of the shiny suits crisis, FINA instructed suit makers to provide used bodysuits on their way too being banned to swimmers who could either not afford them or had no access to them in an effort to level the field at a time when non-textile apparel was clearly conveying different ‘benefits’ to swimmers of different build and fitness.

FINA leaders are believed to have held talks with two possible manufacturers of the kind of full-face scuba mask and snorkel Tokyo organisers are calling for swimmers to wear in warm up and swim down at the Olympic Games.

More on this breaking story and reaction from swimmers and coaches later in the day.

Meanwhile…

A whirlwind history of goggles

The first known goggles are believed to have been invented in Persia in the 14th Century. Originally made from polished tortoise shells, for transparency, they were used by pearl divers.

Later, Polynesian skin divers developed downward-only wooden goggles with deep frames that trapped air harnessing the pressure of water against the downward movement of the dive. Good for the down, not for the up.

By the early 20th century, industrial and technical developments brought on the age of the “modern goggle”, worn by swimmers crossing the English/French Channel from 1911 onwards. Thomas ‘Bill’ Burgess is credited with being the first person to use goggles to cross the channel and whilst this is strictly true, he did not actually wear swimming goggles. Instead he used motorcycle goggles that were not full waterproof and required regular emptying.

In 1916 a patent was given for the production of swimming goggles, but there is no evidence that they were ever manufactured. In 1928, when Gertrude Erdele beat the boys on the clock to become the first woman and fastest ever swimmer to cross the channel crossing – and the first toe use freestyle diving it – she too wore motorcycle goggles, though sealed with paraffin to ensure they were watertight.

During the 1950s open water swimmers including Florence Chadwick used rubber goggles with double lenses. These goggles were large and a bit ungainly but protected the swimmer from saltwater and improved visibility in the sea.

The adoption of goggles in competition was delayed by a rule in the 1960s that disqualified any who used any such equipment in racing at a time when some had and some did not. 1969 saw the revolutionising of swimming goggles as Tony Godfrey began manufacturing the ‘Godfrey Goggle’. Godfrey tested several plastics before opting for polycarbonate in his designs: light, thin, hard wearing and shatter resistant.

In 1972, Scot David Wilkie, of Britain, became the first Olympian to compete wearing both goggles and a swimming hat. The rest is history, too – just more known among all of you.

One quirk in the stream of development was related to Open Water swimming. In 2016, a pair of goggles that impair the vision of the swimmer to replicate open-water conditions was in the making, a patent application suggested.

There was no company or institution assigned to the patent application cited in the Politics and Government Week in an article supplied by VerticalNews cites the ‘inventors’ as saying: “The embodiments herein relate generally to athletic accessories, and more particularly, to a swim goggles for improving swimming technique.

“Swimming in open water proves to be a difficult skill to learn. Visibility in the water is limited, and the swimmer must use the technique of sighting to know his or her direction. However, most swimmers learn and practice swimming in a swimming pool. In this environment, the swimmer has clear water to see in, lanes to stay in, and lines to guide them. This prevents them from efficiently learning the technique of sighting, which is a critical aspect of open water swimming.

“Therefore, what is needed are swim goggles comprising a mechanism that blocks a portion of the lenses to mimic the field of vision available to a swimmer when swimming in open waters.”