Memories Of The Tokyo Olympic Games In 1964 – Dawn Fraser’s Triple, A Royal Pardon & All That

The Olympic Games will get underway in Tokyo next weekend after a delay of a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Japanese capital first hosted the world’s biggest multi-sports event in 1964, when the Opening Ceremony and lighting of the flame took place own October 10. Ahead of Tokyo 2021 coverage, we look back 57 years to some of the highlights of a pioneering party in the pool.

The first Tokyo Olympic Games the premier multi-sports showcase to Asia for the first time and delivered standout lines in swimming history. At the helm of them all was Dawn Fraser‘s victory over 100m freestyle, a third consecutive triumph that delivered founder membership of the triple crown club for the Australian sprinter. Fifty Seven years on, the club has just two other ticket holders, Hungarian Krisztina Egerszegi (200m backstroke, 1988, 1992, 1996) and Michael Phelps (200m medley, 2004, 2008, 2012, with 2016 making the American the founder member off the quadruple crown club; and 200m butterfly, 2004, 2008, 2016).

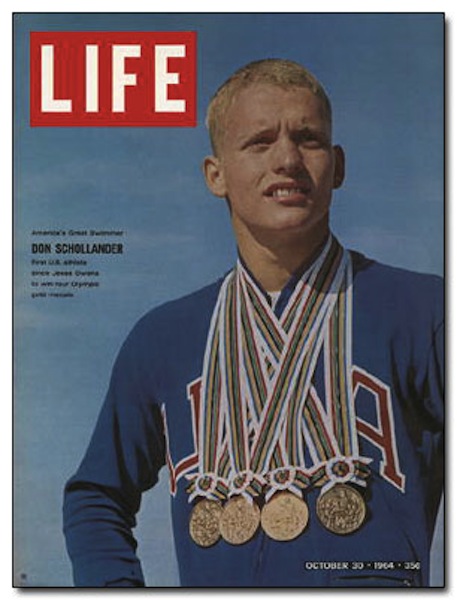

The Tokyo Games, the first to be fully televised, also witnessed a pioneering achievement among men in the pool: American Don Schollander became the first swimmer ever to win four gold medals at one Olympics. Such success landed him on the cover of Time Life.

The opening ceremony on October 10 was followed by the first swimming events the next day. Forty two nations sent swimmers to the a meet stretched over eight days between October 11 and 18. By the close of business, 13 world records had fallen, nine of them to men. The USA topped the medals table with 13 gold and eight of each of the other colours, Australia next with four gold, a silver and four bronze, the Soviet Union third with a golds, a silver and two bronzes.

Pioneering Moments In Games History

Fraser’s big moment unfolded on day 3 of racing, when made in three in a row by holding off Sharon Stouder, a 15-year-old American who won three gold medals, over 100m butterfly (1:04.7, world record) and in world-record breaking 4x100m freestyle (4:03.8) and medley (4:33.9) relays. The women’s events marked the advent of breaststroke legend Galina Prozumenshikova (URS) and a pioneer of multi-skills and multi-eventing, Donna de Varona (USA). Schollander’s victories unfolded in the 100m and 400m freestyle and his leading role in two relays contributed to a dominant American performance that reaped 29 medals.

Of the 42 nations represented at the domed “temple of swimming” National Gymnasium Pool, 41 were represented by men and 27 by women. Iran, South Korea and Thailand made their debuts in Olympic waters at a time when the competition programme was expanding, too. Of the 18 events, 10 were open to men, eight to women. The price of adding a 200m backstroke, a 400m medley and a 4x100m freestyle relay to the men’s programme was the loss of the 100m backstroke. Women raced the 400m medley for the first time at the Olympics.

Dawn Fraser Returns To Tokyo And The Scene Of Victory, Scorn & Emperor’s Pardon

Dawn Fraser, the Australian pioneer of sprint swimming, returned to Japan on October 9, 2014, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics at which she claimed an historic third victory in the 100m freestyle – and then got slapped with a 10-year ban by her national swim federation.

After her success in the pool, Fraser was arrested by Japanese police for attempting to take a flag to keep as a souvenir following a party on the last day of the Olympics.

At 77 and an official “Australian National Living Treasure”, Fraser said that she would “think twice about souvenir-ing a flag”. Fraser added:

“The flag incident was an over-reaction by swimming officials considering I had been given exemption for a week from the Olympic team when it happened.”

Dawn Fraser – image, with Aussie kids in the swim, having fun and learning awareness and safety – photo by Deli Carr, courtesy of Swimming Australia

Dawn Fraser – Games Legend

Born on September 4, 1937, Fraser became the first woman to race inside a minute for the 100m freestyle with a 59.9 effort on October 27, 1962. Winner of the 100m at three Games, the Balmain Bullet might have made it four but for the high-handed bureaucracy of the Australian Amateur Swimming Union in response to the swimmer’s high jinks at the 1964 Olympic Games.

Fraser won her first 100m crown in front of a cheering home crowd in Melbourne, beating teammate Lorraine Crapp by 0.3sec in a world record of 1:02.0, Australia celebrating the sweep as bronze went to Faith Leech.

In Rome four years later, she became the first woman to retain the title – doing so in 1:01.2 some three metres ahead of American Chris Von Salza – then set an Olympic record of 1:00.6 leading off an Australian freestyle relay that included Ilsa Konrads, Crapp and Alva Colquoun that won the silver medal in 4:11.3 behind a world record of 4:08.9, which went to the USA quartet.

![Faith Leech, right, with Dawn Fraser and Lorraine Crapp [courtesy: ES Archive]](http://www.swimvortex.com/wp-content/uploads/FaithleechDawnFraserLorrainecrappbio-250x159.jpg)

On October 23, 1962, Fraser clocked 1:00.0 over 110yd in Melbourne and made history four days later with a 59.9sec effort to qualify for the Commonwealth Games in Perth. There, on November 24, she reduced the mark to 59.5. On the last day of February, the 29th, in leap-year 1964, Fraser swam the last of her 10 100m world records, spanning eight years, in 58.9.

A couple of weeks later, Fraser was driving home from a social event at a football club with her mother, sister and a friend when her car skidded and collided with a parked truck. Mrs. Fraser was killed, Dawn’s sister was knocked unconscious and Fraser herself spent six weeks in plaster while a chipped vertebra mended itself.

Incredibly, Fraser was back in shape seven months later and her sporting immortality was confirmed on October 13, when she claimed the Tokyo Olympic crown in 59.5, 0.4sec ahead of the second woman to break a minute, Sharon Stouder of the USA, a result described in the US as “Stouder’s silver behind Old Ma Fraser”, who was 27 by then.

Coached by Harry Gallagher in Sydney, Fraser was the youngest of eight children born into a working-class household in Balmain, then an industrial suburb of Sydney. She was 18 when, on February 21, 1956, she shaved 0.1sec off Dutchwoman Willie Den Ouden’s 20-year-old 100m freestyle record with a 1:04.5. The same year saw Cockie Gastelaars (NED) lower the mark to 1:04.2 and 1:04.0, Fraser to 1:03.3, and then Lorraine Crapp to 1:03.2 and a then stunning 1:02.4.

At the Melbourne Games on December 1, Fraser’s 1:02.0 world record victory marked her second global mark over 100m in what would become a record-breaking run of two world records and 15 years at the helm of pace. The 58.9 with which she closed her account was equalled by fellow Australian Shane Gould in London, April 1971 on her way to writing another outstanding line in history: Gould’s collection of five solo podium places, topped by three golds, each won in a World record, remains a record to this day.

The night before Fraser’s 1956 final, and her first international outing, the champion-to-be had a nightmare, which she described in her autobiography, Below The Surface:

“The gun went off but I had honey on my feet and it was hard to pull them away from the starting block, I finally fought free and dived high. … the water wasn’t water, it was spaghetti.”

The real race, in real water, saw Fraser and Crapp battle stroke-for-stroke well ahead of a pack from which Faith Leech emerged as bronze medal winner to give Australia a clean sweep. Fraser celebrated by borrowing a ladder from a TV crew, climbing into the stands to hug her parents and dedicate her win to her late brother Don, the man who introduced her to swimming.

Eight years on, Fraser was named Australian of the Year, but just days after she had enjoyed a lap of honour in a car around Melbourne racecourse, she received a 10-year suspension by the AASU (later, and too late for a comeback, reduced to four years), preventing her from defending her crown at a 1968 Olympic Games that saw the 100m won in 1:00.0.

Her misdemeanors: parading at the Opening Ceremony in Tokyo against orders; attempting to steal a flag in a midnight raid at the entrance of the Emperor’s Palace. For the latter, she was arrested and charged but not only did the Emperor pardon her, he gave her the flag as a gift.

At the time, she was accused of swimming a moat to steal the flag. Years later, she told this author:

“I did not swim the moat, get it right. I just would never have done that – and I didn’t do. We got up to all sorts of tricks … but a lot of things they said were just not true.

Fraser’s return to Tokyo 50 years after one of the most controversial lines in swim history unfolded in a week that saw the leading name of this era in the sport, Michael Phelps, barred for six months and removed from the USA world-championships team for 2015 after an admission of drink driving. After he retired after another soaring Olympic campaign at Rio 2016, Phelps spoke out about the mental-health issues he suffered during his career as a result of the pressure he felt during the most extraordinary Olympic bull run and career there ever was.

Games Relay First For Clark

One among the count of world records set at the Tokyo 1964 Olympics wrote two new lines in swimming history: Stephen Clark (USA), who had failed to make the US team for the 100m freestyle, made history by becoming the first swimmer in Olympic waters to set a world record (52.9, matching the mark of Frenchman Alain Gottvalles) leading off a relay. That effort in the 4x100m freestyle gave Clark the freestyle berth in the winning USA medley relay and stopped Schollander from winning a fifth gold medal (he did not race in the rounds, nor were medals granted to relay heats swimmers in those days).

Tokyo was a pioneering Games for swimming on several levels. Among firsts was the use of automatic timing in Olympic swimming. The system used was developed by a team at the University of Michigan and had been first tested at the Commonwealth Games in Perth, Western Australia, in 1962. It was still in test mode in Japan but marked the first challenge to the human-eye and thumb on stopwatch when it came to close calls and medal decisions.

Controversy followed the 100m freestyle in which 0.1sec split Schollander (53.4) and Bobby McGregor (GBR) for gold and silver. It was the bronze that caused a fuss: the time of 54.0sec was shared by Hans-Joachim Klein (GER), and American Gary Ilman. Judges turned to the automatic system and found that Klein’s time was neither a tenth nor even a hundredth of a second faster than Ilman’s: it came down to a thousandth. They deemed that sufficient evidence to declare Klein the sole winner of the bronze medal.

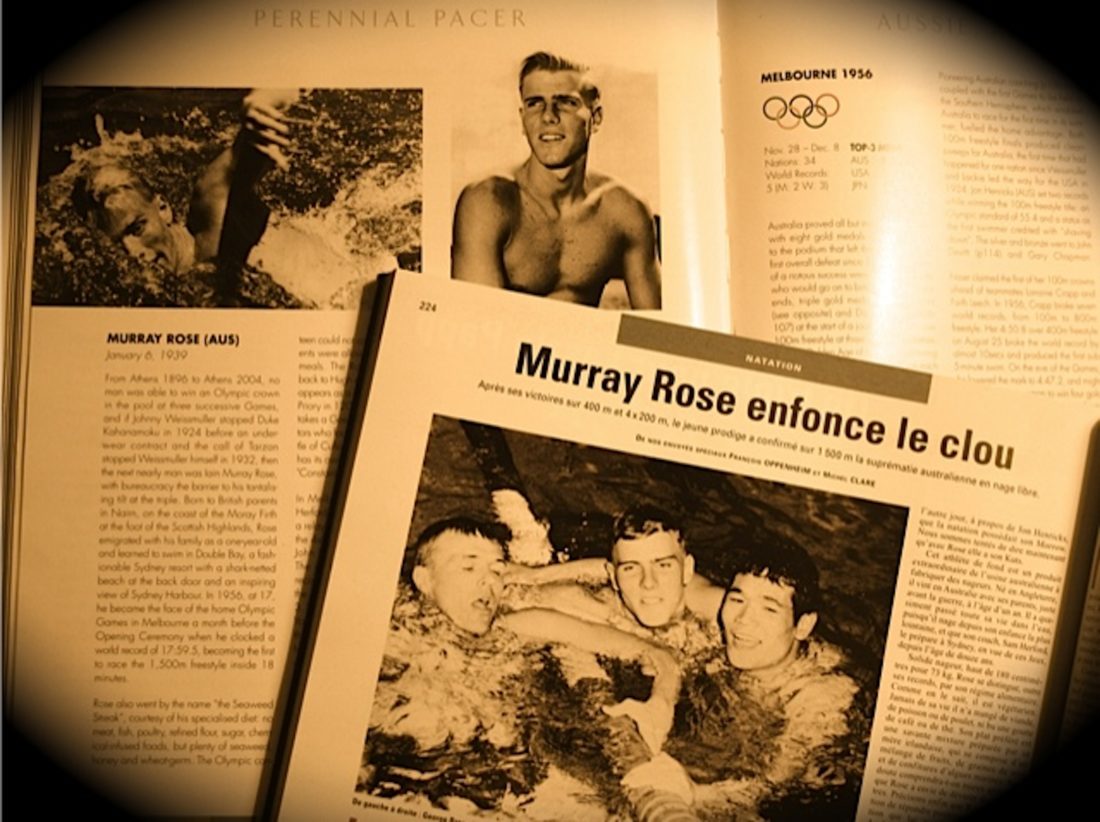

Beyond Schollander & in the absence of Rose

Meantime, Schollander [ragout, right: L’Equipe’s Les Jeux Olympiques], the first man under 2 minutes over 200m freestyle (an even that made its Olympic debut in 1968) dominated the 400m free in a world record of 4:12.2 and brought home both USA freestyle quartets to world records of 3:32.2 (4x100m) and 7:52.1 (4x200m). An American sweep of freestyle events was halted by Robert Windle (AUS), who claimed the 1,500m title in an Olympic record of 17:01.7.

That time was an Olympic record 0.01sec inside the standard in which Murray Rose had established a world record on August 2 that year, 10 weeks before the Tokyo Olympics. Rose, champion in 1956 and silver medal winner in 1960, was not selected, however, because he did not return home to Australia from the United States for trials in February, 1964 [Photo Montage: FINA Aquatics; L’Equipe – Les Jeux Olympiques].

A month after Rose set his last world record, Roy Saari (USA) became the first man under 17mins with a 16:58.7 effort at trials in New York. Like Schollander, he had had a target of four gold medals, but in Tokyo, suffering from a heavy cold, he finished 4th over 400m and raced 30sec slower for 7th place over 30 laps. His sole gold came his way as a member of the 4x200m relay, and he claimed silver in the inaugural 400m medley behind teammate Richard Roth, who had suffered an acute attack of appendicitis three days before his race. Roth, 17, refused to be operated on and raced to a world record of 4:45.4.

The 200m backstroke in Tokyo was publicised as an inaugural event. In fact, the event was making its comeback after a long absence. Ernst Hoppenberg (GER) won the crown in 1900 before the big sleep. Its reintroduction saw Jed Graeflead an American clean-sweep in a world record of 2:10.3, 0.1 ahead of Gary Dilley and Robert Bennett. Backstroke sprinter Thompson Mann was excluded from solo events: he became the first man under a minute over 100m in Tokyo, at 59.6, leading the USA medley relay to a world-record victory in 3:58.4, the first sub-4-minute effort. The 100m returned to the programme in 1968.

Among upsets in Tokyo was the victory of Ian O’Brien (AUS) in the 200m breaststroke. He moved to Sydney when his father died in 1961 to swim for Terry Gathercole, the retired world record holder who had become a coach. In 1962 he won three Commonwealth Games gold medals but his times did not place him in the frame for Tokyo gold. With eight world records to his name, Chet Jestremski (USA) was the man to beat. And beaten he was, into third by O’Brien’s world record of 2:27.8 and Gyorgy Prokopenko (URS), just 0.4sec outside gold and 1.4sec ahead of the American.

The 200m butterfly title was a runaway victory for Australian Kevin Berry (AUS). In days when swimmers had to supplement their incomes, Berry washed dishes at a Sydney steak house where the Australian Olympic Committee held a reception for the team bound for Tokyo: he changed into his blazer for the bash, and then slipped back into his overalls to wash the dishes. Years later, Berry was head of media operations at the Perth 1991 world titles. What made him good on the big occasion as a swimmer was still on show: all big events throw up problems/glitches, the best immediate response the one Berry always had – what can we do to set it right? (as opposed to, who is to blame, followed by much time wasted and no speedy solution to whatever the problem happens to be).

Gold Gone But Another One On The Way

Swimming history, meanwhile, is stacked with those tipped for gold before falling shy. In the case of Virginia Duenkel,her miss in the event that had her name on the gold medal before the race, was not the end of the story.

The final of the 100m backstroke, in which she entered as world record holder at 1:08.3, was never going to be an easy affair: it contained six past and present world record holders over metres and yards swims. Duenkel was leading until 10m to go, when she made the mistake of looking to see where her rivals were. All three medal winners raced below the world record, the title going to Cathy Ferguson (USA) in 1:07.7, with Christine “Kiki” Caron (FRA) claiming a European record of 1:07.9, and Duenkel third in 1:08.0.

Four days later, Duenkel led an American clean sweep in an Olympic record of 4:43.3 in a 400m freestyle featuring Fraser in 4th just 0.4sec shy of the podium in the fastest eight laps of her career, at 27 years of age. That marked her last Olympic appearance before she was barred by Australian swimming for 10 years [ragout: L’Equipe’s Les Jeux Olympiques].

Prozumenshikova started something big when, at 15, she was the first Soviet swimmer to win an Olympic title. Her 2:46.4 (Olympic record) victory by 1.2sec over 14-year-old American medley star in the making Claudia Kolb (USA), was followed by bronze medals in 1968 and 1972 (the latter under her married name of Stepanova and racing as a mother). The generation she enthused won all six medals over 200m at the 1976 and 1980 Olympic Games. Prozumenshikova, also winner of silver medals over 100m in 1968 and 1972, and the first woman to reach the breaststroke podium at three Games, remains the only woman to have won five Olympic medals in the stroke. She broke the 200m world record five times and the 100m once.

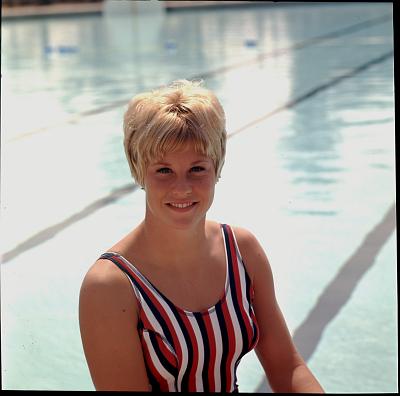

Pioneer of Medley and More – Donna de Varona

Donna Elizabeth de Varona was the sport’s pin-up girl of the 1960s. One of the most photographed women athletes of her age, DeVarona was a star of US nationwide swim suit adverts and cover girl for Life and Time magazines, the Saturday Evening Post and twice for Sports Illustrated. Four years after her Olympic debut in Rome at 13 (when she swam the heats of the 4x100m freestyle relay), DeVarona raced in a class of her own to win the inaugural 400m medley (5:18.7) and with teammates Sharon Stouder, Pokey Watson and Kathleen Ellis set a world-record (4:03.8) to win the 4x100m freestyle relay.

Those efforts led to deVarona being feted as America’s Outstanding Woman Athlete and Outstanding American Female Swimmer, and San Francisco’s Outstanding Woman of the Year.

Between 1960 and 1964 DeVarona was the best all-rounder in the world: she set a record six world records in the 400m medley (5:36.5, 1960, down to 5:14.9, 1964), held the world 100m backstroke record (1:08.9, 1963), and was a member of three world-record breaking relays in 1964, two for Santa Clara SC (4:08.5 over 4x100m freestyle and 4:38.1 over 4x100m medley) and one for the USA at the Tokyo Games.

Domestically, DeVarona won 37 individual national championship medals on backstroke, butterfly and freestyle, including 18 golds and three national high-point awards.

Born in San Diego, California, De Varona went on to become an accomplished broadcaster and after-dinner speaker, has travelled the world campaigning for women in sport and co-founded the Women’s Sports Foundation.

At a dinner in 2007, De Varona said: “100 years of women in swimming. Our history is rich not only for the world records and Olympic medals won but for the men and women who have through their dedication inspired excellence, forged social change, fought for fairness, and created a network of individuals worldwide who are dedicated to making a difference in a world constantly seeking common ground.

“Time, place and circumstance are the gifts to our talents. Great coaching and the opportunity to share the water with others who are as passionate and dedicated has made water sports a cornerstone for all the world and especially the Olympics. NBC would have a very difficult time with those ratings if the Games didn’t start out with swimming. Those of us who have made it to the top of the victory stand know that we didn’t do it alone. A rival is just as important as a coach. However, when the fierce days of competition are over, it is the friendships forged through mutual respect that count the most.”

Donna de Varona

A fine message just as relevant as we approach Tokyo 2021 as it has ever been.