Kliment Kolesnikov Tops 100m Russian Rockets With 47.31 Record Blast

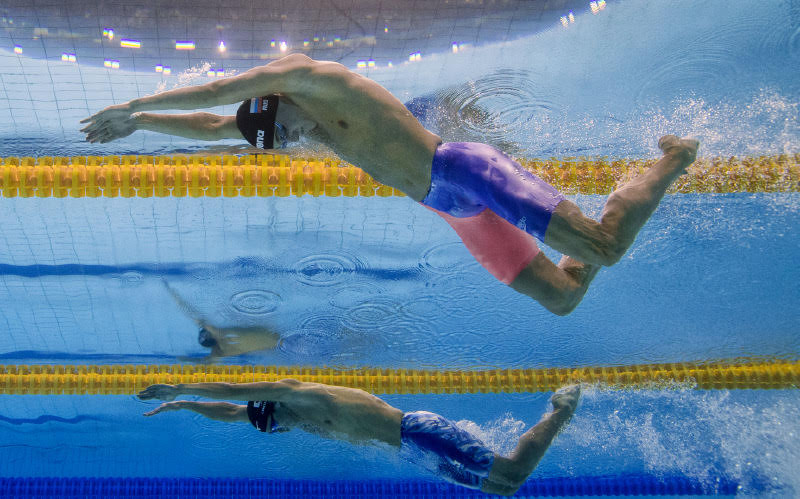

Russian rockets were at the ready today in Kazan for solo and relay action at the Tokyo Olympics come July, the best burners on Kliment Kolesnikov, a 47.31 Russian-record victory elevating him to 5th all-time in textile and 10th all suits. In textile, Kolesnikov is the fastest European in history.

The speed didn’t stop there: next home was previous record holder Andrei Minakov, on 47.77 for Tokyo ticket No2, the door to the podium slammed shut by Vladislav Grinev in 47.89, compared to the Russian record he held at 47.43 until today.

In the battle for 4x100m berths came Vladimir Morozov, 48.18, Alexander Shscegolev, 48.24, and Ivan Giryov, 48.34. The quartet plus reserves have the potential to make the Olympic podium – and if they do, the IOC flag will fly up the pole, the Russian one destined to stay folded in a cupboard this year, courtesy of the doping crisis that has engulfed Russian sport in recent years.

The splits compared:

- 22.55 – 24.76 – 47.31 – Kliment Kolesnikov today

- 22.29 – 24.67 – 46.96 – Caeleb Dressel – World title, 2019

- 22.79 – 24.29 – 47.08 – Kyle Chalmers – World silver, 2019

Equilibrium counts.

The European record survived the day: it stands yet at 47.12 to France’s 2008 Olympic champion Alain Bernard. He clocked that for silver at the Rome 2009 shiny suits circus but had gone faster at French nationals month earlier. His 46.94 on that occasion was discounted, however, because Bernard wore a 100% non-textile suit that FINA described as “unapproved” in a series of flip-flop decisions that made the 2009 season a farce, and not only a French one.

The top one doesn’t count… it was in an “unapproved suit… ” ha! so that makes Bernard’s 47.12 the European record for silver behind Cieklo at Rome 2009

Kolesnikov is World No1 for 2021, though the trials of the main contenders, including Olympic champion Kyle Chalmers of Australia and World champion Caeleb Dressel of the United States, are yet to unfold.

Kolesnikov led the Russian relay to gold with a sizzling 48.04 split at the Youth Olympics in 2018. The freestyle potential of a backstroke force gathering momentum was clear. It was not until semis yesterday that Kolesnikov hinted at the progress made: 47.60, fourth best Russian time ever.

Today, the all-time textile list looks like this:

46.96 Dressel, Caeleb, USA World Champion 2019

47.04 McEvoy, Cameron, AUS World silver 2015

47.08 Chalmers, Kyle, AUS Olympic champion 2016

47.10 Magnussen, James, AUS Olympic silver 2012

47.31 Kolesnikov, Kliment, RUS

47.39 Held, Ryan J, USA

47.43 Grinev, Vladislav, RUS

47.52 Adrian, Nathan, USA Olympic champion 2012

47.57 Minakov, Andrei, RUS

47.61 Rooney, Maxime, USA

Dressel and Chalmers lead the betting on who might emerge the Tokyo blue-ribband champion – and the wagers are heavily on a sub-47 finish not only for the winner. In the heat of the moment, anything can happen, Olympic history screams from its Heights.

Kolesnikov is a reach away from the very best of ’em – and at 47.31, he has just swum faster than any Olympic champion in history barring the shiny suits moment of Beijing 2008, when Alain Bernard, of France, stopped the clock in 47.21.

Chalmers claimed gold in a dominant 47.58 in 2016, the time a World Junior Record, while Nathan Adrian‘s 2012 victory took 47.52, 0.01sec ahead of Aussie James Magnussen. The last Russian to win the Olympic 100m crown was Alex Popov, on 48.74 back in 1996, when he became the first man since Johnny Weissmuller in 1928 to retain the 100m crown. Since then, that club of few has grown by just one man: Pieter van den Hoogeband, in 2004.

No predictions here but the 2019 World Championship podium indicates the Tokyo travel of direction:

Caeleb Dressel – 46.96; Kyle Chalmers – 47.08; the bronze to Vladislav Grinev in 47.82, scope for anyone on 47.5, let alone 47.3 to muscle in on the medals. There’s crystal-ball glazing of a sub-47 podium. There may be rain, there may be sun that day, too.

As things stand this day, the Russian relay has a good shot at the medals in IOC colours – and could also challenge for gold on the day.

From The Craig Lord Archive – April 2017

Meeting Kliment Kolesnikov For The First Time…

It may be tempting to think of Kliment Kolesnikov‘s best backstroke efforts of 54.03 over 100m and 1:55.49 over 200m – the latter the third in the world so far this year and a world junior record – as the results of a boy physically developed beyond his age.

I met the young speedster this weekend at the Energy Standard Cup in Lignano along the coast from Venice and can reveal the good or bad news, depending on the angle you approach it at: the idea of a man in boy’s bathers is wishful thinking. He’s a (tall) strip of a kid with a schoolboy smile and an awful lot of muscle to put on bones yet.

Kolesnikov stands 194cm tall and weighs in at 78kg. He’s a strip of a swimmer compared to the likes of double Olympic champion of 2016 Ryan Murphy, of whom the same could have been said a few seasons back through a selfie timewarp.

The American and the Russian were born in July, five years and a week apart. Just shy of his 17th birthday, Murphy broke 2mins for the first time with a 1:59.79. At almost precisely the same age, we find Kolesnikov on 1:55.49.

Stunning speed. Watching him shift smoothly up the pool here in Lignano on a day of 1:58.81 over 200m backstroke in the morning, 54.59 in the 100m back later the same day and then a 22.57 lifetime best by almost half a second in the 50m free, you’re left in no doubt that we’re looking at one of those who may well fit the forecast of Milorad Cavic, Serbia’s Olympic and Worlds medallist, when he told juniors from Russia, Ukraine, Spain and Germany that “… yes, we will have Olympic champions here tonight but in the future”.

There’ll be a longer wait before we see Kolesnikov reach potential, his backstroke speed drawing the eye, his freestyle dash today evoking memories of Alex Popov, the double-double Olympic freestyle sprint champion of 1992 and 1996 who started out on his back, rolled over and never looked back.

Kolesnikov cites the 200m free (best time: about 1:50, he says) among his aims. He stands out in the crowd of talented youth taking part in a fun, team-based event here in Lignano at a pool where the roof, mercifully for those gathered below rafters rattling to the roar and charge of it all, is supported by massive timbers.

Treating Kolesnikov as a tree among many in the woods of world-class juniors is not an easy task – but it is essential, says Energy head coach James Gibson. This is where the Russian belongs and needs to be, with his clubmates, schoolmates, age peers from several countries, forming friendships, building two-way respect, starting out on a long journey with feet firmly on the ground.

Dynamics warp with time and experience. Kolesnikov’s curve is about to get steeper: he will warm-up at the European Junior Championships in Netanya, Israel, from June 28 to July 2 before turning 17 a week later and then heading off to Budapest for the his World-Championships debut for Russia.

Easy does it, says Gibson, the 2003 world 50m breaststroke champion who guided Florent Manaudou to Olympic gold in the freestyle dash at London 2012 early in his coaching career. Gibson then left Marseilles for Loughborough and steered Fran Halsall to the Commonwealth and European crowns and a world-textile best in 2014 and three more continental golds in 2016, and this season includes in his Energy squad Ben Proud, the Brit who blasted a 21.32 last month.

Gibson now has a third sprinter in the realm of “fastest two ever” when it comes to dashing efforts in textile suits. Kolesnikov may one day join that club.

Look back at Manaudou at 17. Where do we find him that year and the next? Not on freestyle but backstroke: 26.80 and then at World juniors a 26.42 in the dash and 56.50 at European junior championships in his 18th year. Same the year after. It was not until his approach to 20, with a 22.69, that we find Florent sprinting up the 50 free ranks two seasons out from making self and sister Laure the first siblings in swim history to claim Olympic gold in solo events in the pool.

A quiet moment with his mates on camp in Lignano at 16 and Kolesnikov clocks 22.57 and wanders through to the warm-down area for a chat with Moscow mentor Dimitry Lazarev, a good name if you happen to be the coach to a swimmer in professional partnership at the heart of a generation that will be looked to for the resurrection of Russia’s reputation in the realm of clean sport. Much more on that and the work underway in the week ahead.

Kolesnikov is home from home in Lignano. He’s been here many times before, on training camps and competitions since before he turned teen. He first came here when he was six years old long before the training started.

His speedy efforts at Russian nationals in Moscow last month followed a camp with Energy here in Lignano back in March. Says Kolesnikov: “I worked very hard in the training on the camp. We work for two weeks very [intensively].”

He recognises there’s a lot more of that to come. Asked about the meat to be put on bone, he smiled broadly and said:

“Yes, I don’t have a lot of muscle. My father was like me. At 17 he was the tallest man in his class but very thin.”

Strength gains are just a part of what the future holds but Kolesnikov emphasises his proprieties as “technique and endurance”, saying:

“When I was young (laughter); I’m still young but before I was 10 years old, my father taught me technique in swimming and that helped a lot and I am now very good with technique.”

That and his long years in the pool (“my father taught me to swim when I was three”) show. Kolesnikov is efficient and smooth, the skills all the more obvious when he slows down to warm down and goes through a series of drills, including a broken backstroke swim in which each arm rotation involves a deliberate arm bend and stretch of the tricep before he extends ahead of each pull.

Natural speed is with him but Kolesnikov wants it to be there when he finishes races, too. He says:

“We’re working on my aerobics and the things that you need at the end of the race, the longer distance work and endurance I need.”

Talk of Popov or anything of the kind is premature as Kolesnikov approaches a summer that will shape his first experience of global senior waters when the going is at its fastest.

Says Gibson:

“We have to remember he’s a 16-year-old school boy. He needs to be a part of the club program, keep his feet on the ground and be surrounded by his peers. It’s critical that the level he’s working at is the correct one for his stage of development, including making sure his focus is also on his schoolwork and that his family gets the support it needs.”

Kolesnikov’s father was a talented athlete, too, but his son says that “at 17 he went away from sport and swimming because he didn’t realise what he could have achieved. He didn’t have an people who could tell him what he needed to do.” Kliment is surrounded by such people – and peers he works alongside and jokes around with on the deck in between races. He says:

“Yes, I’m very lucky. All the people around me help me and my teammates.”

Lazarev is following Gibson’s advice on training cycles and more but the guidance from the head coach extends to care and culture, complete with exposure to the likes of Cavic, Evgeny Korotyshkin, Peter Mankoc and others from the stable of ADN Swim Project athletes serving as mentors to the next wave.

This week marks the arrival of Chad Le Clos at Energy’s base in Turkey at the start of summer preparation for the world titles. The club now has bases in Moscow and Kiev, too, its spectrum of preparation from developers to the Olympic, World, continental and regional champions on its books.

The juniors attending events such as the Cup this weekend “were exposed to the seniors, to learning and they gain perspective … that’s an important part of the process, too”, says Gibson.

In his days at Marseilles, Gibson would walk his swimmers up to the top of a hill overlooking the bay and ask them what it was that they wanted to achieve. The mantra he expected to hear and what he wanted his charges to repeat to themselves over and over was “to be the very best I can be”.

“We can ask no more,” says Gibson, thinking laterally along a wide spectrum of building blocks that underpin outcomes in pool and on clock when the big lights are on. “

So, what is Kolesnikov like? Says Gibson:

“He’s a team player. He’s got great discipline. He’s a young lad, he’s grounded and he’s very clear about what he wants: he wants to be the best swimmer in the world. He’s excelled on backstroke but he’s doing freestyle, medleys, developing his all-round skills. We don’t want to limit him by a narrow focus of one stroke at this stage in his development.”

Especially not when you have a boy going 2:00.27 over 200m medley, as the 16-year-old did today in Lignano to enter the top 30 rankings in the world so far this year.

This summer in Netanya and Budapest, Kolesnikov will race as a boy among boys and a boy among men. By the time the world gathers for pre-Olympic season worlds in 2019, he will be approaching what may be his first Olympic season – and by Tokyo 2020 he will be the same age that Popov was when he gave a hint of things to come in the summer of 1991 on his way to breaking the American sprint lock of Matt Biondi and Tom Jager with a stunning Olympic debut and double in Barcelona.

Impossible to say what the program will be by then. No guarantees on any front, either, though the runes read well.

Back to Kazan, April 2021 …

Olympic & World Champions Weigh Each Other Up

Not much had separated Olympic champion Dmitry Balandin, of Kazhakstan, and World champion and one of the other Russian rockets bound for Tokyo honours, Anton Chupkov, in the semis, Kirill Prigoda right there with them: 2:08.42 2:08.54, 2:08.84, in that order.

The final didn’t change much, except that Anton Chupkov got to the wall first, in 2:08.31, Dmitry Balandin on 2:08.85, with Kirill Prigoda third in 2:09.77, just ahead of 19-year-old Alexander Zhigalov, on 2:10.28.

All a far cry from the drama in Tokyo today, when Shoma Sato took down the Asian record with a 2:06.40. The Olympic Games will be a different kind of battle.

Joining the Russian rockets heading to Japan this summer is another 19-year-old: Aleksandr Egorov will make his Olympic debut in a debut Olympic event this July after winning the 800m freestyle crown in 7:48.25.

Two Ilya’s followed. On 7:53.92, Ilya Druzhinin took the second ticket to a Tokyo Games at which Russian athletes must compete as neutrals because of Russia’s penalty in a doping crisis of its own making. The podium was completed by Ilya Sibirtsev in 7:55.48.

There were no tickets to Tokyo in the women’s 200m butterfly, Svetlana Chimova the champion anew on 2:08.98, ahead of Alexandra Sabitova, 2:10.37 and Anastasia Markova, 2:10.93.

In semi-finals, 100m champion and World 200m champion Evgeny Rylov rumbled out a 1:55.34 to take lane 4 for the final of the 200m backstroke in a fashion that leaves his rivals in no doubt: they’re be battling for the minor spoils.