Katie Ledecky & A Legend’s Perspective In The Space Between Loss, Loss, Gain, Retain

The exacting standards of Kathleen Genevieve Ledecky and where they led her and her sport to in a time of pandemic and heightened empathy and perspective at the Tokyo Olympic Games offered us two overriding narratives: there was the surface story of the most decorated distance freestyler in history racing a rollercoaster to two golds, two silvers, one missed podium among two lost titles, two historic firsts, over 800 and 1500m, and all the determinations and courage all of that took atop the bigger work of many years; and then, in the depths, a tale of great expectations and how those impact even the superheroes who seem to be the very breeze in the sails of success.

Perspective is what Ledecky called for after losing two crowns on her way to becoming the most decorated woman swimmer in Olympic history, with six golds and seven medals in all in solo events.

Deeper understanding. Yes, there was Ariarne Titmus, Emma McKeon, Caeleb Dressel, Adam Peaty et al, all with rich stories and twists in tales of towering determination, discipline and dedication. They drew the eye with pantheon-rattling achievements that helped draw others to their own new heights and provided us with some of the highlights of the Games across all sports. Without detracting from any of that, where would we alight if we were to teleport ourselves forward to 2040 and search for the story that reflected the age, the hour, the specific circumstances and challenges of a COVID-delayed Olympics?

Ledecky is where we might stop to sup a cup of 2021 vintage.

There was the heat of the moment, of course: loss, loss, gain, retain. Spectacular stuff. The rich vein of deeper understanding was provided, however, by the brackets in between loss (pain and pressure), loss (perspective), gain (relief, redemption, resilience and maturity), retain (legend and lore, sporting immortality sealed).

The Four Podiums (& One ‘Miss’) Of Katie Ledecky in Tokyo:

- 400m freestyle: Ariarne Titmus The Terminator Pays Plaudits To Pioneer Pacesetter Katie Ledecky At The Changing of the Guard Silver

- 200m freestyle: Ariarne Titmus Punches Green-&-Gold Double Ahead Of Haughey Hong Kong High Fifth

- 1500m freestyle – Tears Of Joy & Relief As Katie Ledecky Punches Pioneering Mind-Over-Matter Gold In Gender-Parity Party In The Pool Gold

- 4x200m freestyle – China Lead Rush Under World Record Ahead Of USA & An Aussie Conundrum Silver

- 800m freestyle – Katie Ledecky Defeats Her Inner Balrog To Become Fourth Member Of Triple-Crown Club 8:12 To 8:13 Over Titmus Gold

That took the count of Olympic prizes in the outstanding pantheon of Katie Ledecky to 10 podiums, seven gold, three silver – all freestyle, over three Games, six of them in solo events. More records for a record book that already boasted her name with a string of entries before the tales of Tokyo unfolded.

At the peak of Olympian Heights, the Games are gladiatorial and have often been far more about victor vs vanquished, winner vs loser, steely grit vs ‘bottled it’, thumbs up vs thumbs down, and so on, than the universality of “it’s the taking part that counts”. Ledecky has never been about “taking part”. She’s been a pioneering powerhouse of the pool and it is because she remained just that after feeling the sting of defeat in Tokyo that there is much-needed room to talk about the issues she raised at a time when the term “mental health” is a vogue suffering from under- and over-use.

During the Games, the instant take on the broader view of Ledecky’s achievement, was best reflected in the work of Beth Harris and Paul Newberry, at The Associated Press: where others could not (too short on time, space, knowledge, perspective, too heavy on bitter criticism or flattery too flowery and fawning) they reported the facts, her words and painted the clearest snapshot of the moment in a way that reminded us that while a picture can be worth a thousand words, it may also leave a false impression (in the gaps between smile, nonchalance, the fade of a frown and the roll of a tear is a world of complexity when it comes to the champion capable of parking a battle on the way to winning a war).

Exacting standards: in sport, providence is the art of living every day with all you do dedicated to getting the parts of highly complex sums and variables as right as you can, day in, day out so that when you come to put all your best habits together in one decisive week of honouring the myriad dress rehearsals aimed at a moment some years, months and then weeks later you might pack a punch that none of the others living such a life less ordinary can withstand.

That is, of course, until, despite your best efforts, you’re not you, or you’re not quite the you you were, or someone else becomes the you beyond you at your best, the chronology of swimming stacked with the stuff. All three of those things applied to Ledecky across the spectrum of her events and experiences in Tokyo.

Regardless of the outcome of providence prepared for (as opposed to the protection of divinity), perspective and perseverance are required. Katie Ledecky was brimming with both in Tokyo, where she spoke eloquently and at times more emotionally than we’ve ever seen her address the media before. The perspective was, hopefully, helpful to all: an Olympic champion at 15 back in 2012, at 24 she was able to speak for the first time in public about feeling the weight of expectation and the pressure that comes with living out her biggest challenges in the full glare of a watching world, some of it waiting for her to stumble, if only to prove that, like them, she’s human after all.

- Final 1: Titmus, tales of a debilitating, chance-rocking shoulder injury having turned out to be more tactic than truth, claws back and overhauls her in the last 100m of the 400m for “upset” gold and “upset” silver on 3:56 and 3:57. They’re fast enough to make the medals among men overt 400 at any time up to any including Munich 1972; and would both have been a stroke or so away from Ron McKeon, Emma’s dad, when he came home 8th in the 1984 final for Australia at Los Angeles, a Games before sub-3:50 eight-length swimming because a reality for men.

- Final 2: Titmus races smart yet again, delivers a knockout blow to rivals and, in keeping the 200m a place of triumph for those coming down in distance over those working up to it (with tremendous Asian-record efforts, Siobhan Haughey claimed silver in both the 100 and 200m) takes another title from Ledecky, over 200m, the American in fifth but focusing on what for her is the bigger fish to fry later in the same session…

- Final 3: the 200m final parked but doubtless with her yet, somewhere in the depths of brain and braun, Ledecky races 1500m at a pace more than a second per 100m slower than her blockbuster World record but that’s good enough for the inaugural women’s 1500m crown to be added to her pantheon. Tears flow. It’s a pivotal moment in the American’s meet.

- Final 4: All the podium inside World record over 4x200m freestyle, China with the edge, Ledecky and Titmus celebrating their third medals of the Games, the Americans taking silver, the Australians a bronze that might have been better on a different day and with a different coach call.

- Final 5: Katie Ledecky saves her best for last, an 8:12 win (after 8:15 in 2012 and a stunning 8:04 World mark in 2016) making her the fourth member of the triple-crown club after Fraser, Egerszegi and Phelps. Titmus is close, on a Commonwealth standard of 8:13.

With that 800m victory, Ledecky seals her place in the pantheon as the most decorated freestyle swimmer in history, with 10 Olympic podiums, six of them in solo events. That took Ledecky one medal beyond the nine freestyle podiums earned by Australia’s Ian Thorpe in 2000 and 2004. Of the 28 medals won by Michael Phelps, 10 were won in freestyle events, eight of those in relays, as opposed to Thorpe’s split of 5 solo medals, including a range of 100, 200 and 400m, and 4 relays.

Some records among greats of women’s freestyle remain beyond Ledecky, including the record medal-winning range of Shane Gould, the Australian who in 1972 claimed a medal in all distances from 100 to 800m, the 200 and 400m delivering gold in World-record time. Gould also claimed gold in the 200m medley in a global standard, for five solo medals at one Games, a feat that no other woman has ever matched, Phelps the only other swimmer to have achieved the feat, having done so in 2008 when he claimed record 8 golds in Beijing. Gould is also the last woman to hold all World records from 100m to 1500m simultaneously (or, indeed, without it being simultaneous).

Sport is like that: even the likes of Gould, Phelps and Ledecky have had some of their record achievements overhauled and while it seems spectacularly unlikely, there will be a day when a swimmer surpasses those 23 golds atop 28 medals, Phelps believes. Few back him on that, so extraordinary and so far beyond next best are those sums.

Even the greats say it: all greatest things come to an end. Sport makes it a matter of when, not if.

The Numbers Game(s)

In Tokyo, Ledecky moved up to all-time No 27 among all sports, all-time, both genders, on the ranking of the biggest Olympic medal haulers in history, with 10 medals overall, the total tally the overriding measure. Such lists rely on relays and are far from imperfect when it comes to measuring the swimmers who made the most impact regardless of which country they came from and independent of the strength of their nation in the pool. In swimming, Ledecky is now queen of the Olympic medals table, having overtaken Hungarian legend Krisztina Egerszegi, who claimed 5 golds atop 7 solo medals in her career. Ledecky is also No 2 overall, all swimmers, behind teammate Michael Phelps:

Men:

| 1 | Michael Phelps – USA 2004-08-12-16 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| 2 | Mark Spitz – USA 1968-72 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 3 | Alex Popov – RUS – 1992-96-2000 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 4 | Roland Matthes – GDR* – 1968-72-76 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 5 | Tamás Darnyi – HUN – 1988-92 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 6 | Kosuke Kitajima – JPN – 2004-08 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

Women

| 1 | Katie Ledecky – USA 2012-16-21 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 2 | Krisztina Egerszegi – HUN 1988-92-96 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 3 | Inge de Bruijn – NED 2000-04 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 4 | Janet Evans USA – 1988-92 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 5 | Yana Klochkova – 2000-04 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 6 | Shane Gould – 1972 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

- – * – Roland Matthes is included in these lists, while other GDR swimmers are not, including Kristin Otto, winner of four solo golds at Seoul, 1988, owing to statements from witnesses and parties involved in the GDR’s State Plan 14:25 systematic doping program that confirmed that Matthes’ coach Marlies Grohe-Geissler had refused to comply with the drugs regime, on grounds that her charge needed no assistance beyond his natural talent and hard work. She was the only coach who had been allowed to do so without being dismissed, according to Dr Helge Pfeiffer, one of the senior sports scientists who worked in the system knowing that doping was a part of the regime.

Mental Health Awareness Among Athletes

The how and in what circumstances is the prevailing and next big question. It is important to note, when reflecting on the Tokyo 2020ne story of Katie Ledecky that she was asked about mental health issues in the context of Simone Biles, the ace gymnast and her Team USA mate. Ledecky did not suggest that she, herself, had been labouring under the strain of mental-health issues but she did make the link between aspects of performance sport that can contribute to ill-health and a lack of mental well-being.

Like Michael Phelps and many other Olympic champions for whom resilience and long years of coping with ‘practice makes perfect’ becomes their daily bread, Ledecky stands out as an example of a great athlete who made it all look so easy. It wasn’t. It never is.

Gold tends to mask the toll being taken in the depths of experience, one swimmers have either never raised at all or have done so only after retiring or, of late, when gold eludes them; and in explaining their emotions they provided insight into the pressures they have endured in a realm where ‘resilience’, ‘being tough’, ‘never give up’ are among mantras helpful when all is well, potentially devastating, even catastrophic, when things go wrong.

It is rare to see things go very wrong (well beyond any finishing position or a time on a clock) on the big occasions. Indeed, on the likes of Ledecky heights, we’re looking at a supreme example of being very well prepared for success in an extremely challenging environment recognised by most of the world as race day, from which they can all walk away from entertained and unscathed come what may, while the athlete, the coach and the parent may for many years to come tow the low of a gold missed by 0.01; a podium by 0.1; a final by a margin unimaginable before the clock stopped.

There are many measures and variables to take account of in sport. Take this aspect of long-term preparation. When asked how she copes with the kind of multi-event program that has become one of the hallmarks of her career, Ledecky said:

“I try to take it one race at a time. I don’t think too far ahead and when one race is done, it’s kinda done and the focus goes to the next one. After the first race, I shift my mindset to the second race almost immediately. That happens whether the first race goes to plan or not. I have to move on from it really quickly and approach the second race like it’s my first of that day and my only race of that day.”

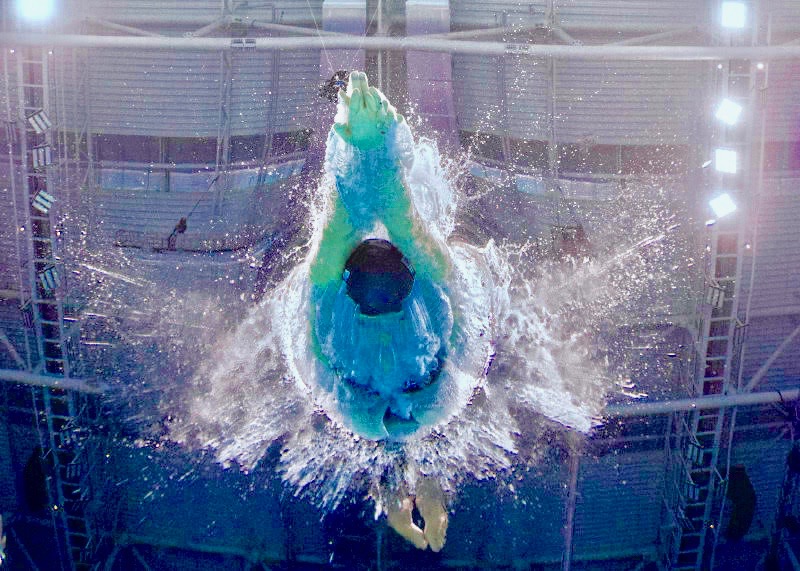

Katie Ledecky – by Patrick B. Kraemer

Imagine, then, the mental strength, as well as physical fortitude, required to suffer two defeats in the heat of pivotal and gladiatorial battle at the heart of a bigger ‘war’ that is one of the focus points of coverage broadcast and print around the world, and then parking it in order to ascend to the top of the Olympic podium not once but twice to bring a third Olympic campaign to a glorious end. Evidence of mental health gone right; gone wrong; at risk? All of that. Regardless of the result. Awareness counts, awareness of what cannot be seen unless a physical breakdown happens before our very eyes – and those are rare, the recent events surrounding Naomi Osaka a clear case in point. Here’s a news report discussing those events, a video chosen because it does not only focus on the reaction of the athlete but on the figures around the athlete, agent, reporter and then commentator and newscaster. I leave you to form your own opinion of what we learn – and what we do not learn – from this:

In the swimming realm, Phelps was hardly the first swimmer, let alone high achiever, to raise the issue of mental health. He might have been motivated and even inspired by the challenges of Grant Hackett, Ian Thorpe, Gemma Spofforth (who tells her own story of struggle with mental health in her book Dealing With It, on which she worked with this author), and others who had previously spoken out on the issue from their own personal perspectives and experiences.

Then the is the story of Sippy Woodhead. It’s among those that has sat there on the swimming shelf for decades waiting for federations, coaches, athletes and parents to pay heed to and find perspective in the lessons of a past too often ignored by those who had governed the sport and those who have found life easier by looking the other way on a whole kaleidoscope of issues.

During the Tokyo Games, a Team USA graphic on the great swimmer, noted the numbers: 28 medals, 23 golds, the size of his limbs, the weight he could squat and press, his age when he first raced at a Games and when he broke his first World record (and they got that wrong)… and on and on. Despite all the messages Phelps has been putting out, despite the Games being an opportune moment to speed that word, the graphic made absolutely no mention of mental health and athlete welfare.

Phelps does – and will continue to do so. He is now playing a significant part in spreading the word. His profile has helped raise awareness of the challenges and pressures felt by athletes who go and grow from pre-teen talent to Olympic podium in something of a bubble of specific existence, circumstance and dedication way beyond what the vast majority of people of the same age ever experience.

The mental-health messages of Phelps and his former teammate Allison Schmitt, also coached by Bob Bowman, are less well known outside the United States but at home they have contributed to an atmosphere in which more athletes feel comfortable about speaking openly on the pressures and challenges they face.

We will hear more on that in a book currently being penned by Karen Crouse, a writer who, sadly, we can no longer read in the New York Times after she resigned in the wake of issues with her employer over the Phelps project. Crouse, at least for now, is the latest in a string of fine mainstream media writers who are no longer covering swimming on a regular basis, if at all. The upside is that the work with Phelps promises to be a fine and instructive read.

Against that backdrop, we saw Ledecky in a new light in Tokyo. Her story highlights the blur, the grey zone, the fine line – depending on how you see it – between mental strength and mental health in a sporting life less ordinary, the challenges often specific to the realm and role required, expected and actually lived.

The women’s 1500m, first swum a little shy of 1500m by men not in a pool but out at sea in one stretch back in 1896, was the key to unlocking gender parity of events in the pool for the first time in Olympic history at Tokyo 2021. Ledecky is now the forever pioneer of the 30-length race for women, her achievement to be celebrated as long as there’s us and water and pools to swim in and folk who see the gold in the red thread of swimming history, tradition and innovation and understand that being able to do today the yesterday times of a Kahanamoku or a Fraser is irrelevant. A key part of what makes it all so thrilling is that Weissmuller and Gould came along, Spitz and Evans, Thorpe and Adlington, Phelps and Ledecky, Milak and Titmus … and so it goes.

Perspective spilled well beyond the water when Ledecky spoke at the Games. Swim status, empathy and bright mind in tow, she had been out in the world to meet children hospitalised with life-threatening illness; veterans maimed and patched back up again after battle.

She referred to the kind of stuff that makes a swimming race, even many more and most of them delivering gold in Olympic and global waters for a swimmer so good that she can stomach her first two solo-event defeats in the full glare of a watching world, super-troupers and Olympic Flames burning, cameras whirring in a crowd-less venue. It might all have felt like ‘lights on, no-one home’ were it not for the excellence, spills and thrills unfolding in the lanes among stepper-uppers and those who have stepped up beyond and, as Ledecky showed, can still knock ’em over when travelling almost 20sec slower than the pioneering pace that may well outlive her days in the fast lane and the careers of generations to come, too.

Ledecky sees the downside of her own exacting standards and excellence. Faster, Stronger, Higher. There always comes a moment when fastest, strongest, highest runs out of time.

“It’s a real blessing – and a curse,” she said with a chuckle at her post-1500m press conference.

After the 400m silver and a fifth place in the 200m, Ledecky had risen to the challenge of champions but before the status got to show its face, we heard along the way such questions as “did you feel crushed”; “did you think you might not cope”; “how do you feel about silver”; “did your world crash”? And so on.

Perspective was her plea to it all. Said Ledecky:

“I’d much rather people be concerned about people who are really truly struggling. It’s a true privilege to be at an Olympics – let alone an Olympics in the middle of a pandemic. So many people around the world are going through a lot of hard things. I’m just so lucky to be here.”

Katie Ledecky – Photo by Patrick B. Kraemer

Mental health was among contenders for gold at the Games in Tokyo, star gymnast Simone Biles and tennis ace Naomi Osaka among those who spoke out about being worn down, and even out, by the stresses and strains of a specific dilemma: pursuing a life of excellence in the realm of world-class performance that supports a sportainment industry worth billions but is in its infancy when it comes to athlete welfare and prevention of bad and harmful practice.

We’ve heard Dean Boxall, high-performance coach to Titmus, talk of insisting on athletes taking responsibility and “owning it” once they’ve declared “Olympic gold” to be their goal. I haven’t asked him if he applies the same principle to himself when it comes to a coaching responsibility that spills well beyond “Olympic gold” but, while I haven’t heard anyone else ask him that question either, I assume he gets the point and takes it seriously.

Not all coaches in history have. Not all parents in history have, either, nor federations, nor others.

In decades gone by, the equivalent of Rio (a second Games) would have been it for Ledecky, if she got a second shot at all (think Debbie Meyer), and we would never have known her as an athlete beyond her teens. Now we do and like many others athletes on a learning curve in their 20s and even 30s these days, Ledecky, the mature athlete, is what swimming needs more of.

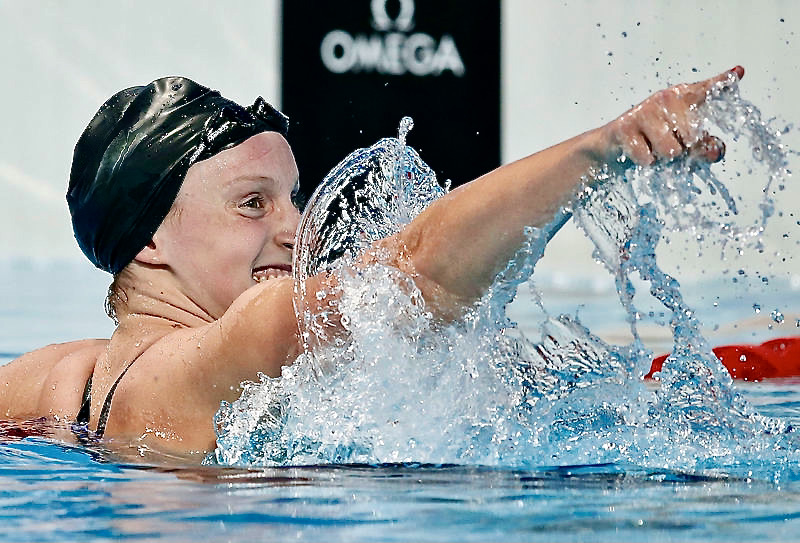

She had missed the podium for the first time in her Olympic career going into the 1500m final. After 30 gruelling lengths down which the American’s performance was much more ‘just do what you know you’re capable of even on an off day’ than about the dominance she has delivered in the past, Ledecky stared up at the scoreboard, registered the familiar “1” and felt a surge of emotion too strong to leave locked in.

She tumbled over the lane rope to give her runner-up teammate, Erica Sullivan, a heartfelt hug, then let out an uncharacteristic scream toward her American teammates in the spectatorless stands. The tears started to flow, a flood threatening, so Ledecky pulled her goggles over her eyes before leaving the pool, not yet ready to reveal the side of her she was about to speak about to the media in a temporary building a short walk away, through daylight absent in the venue.

Her voice choked with emotion, Ledecky struggled to hold back the tears as she spoke of her family and then answered a question about ‘winning and losing’ and what the difference meant to her. If there was a mental-health issue in play it was not the result or her form or the result of others that Ledecky was concerned about. Pleading for we, the observers, to find the perspective that reached for, she said:

“After the 200, I knew I had to turn the page very quickly. In the warm-down pool I was thinking of my family. Kind of each stroke I was thinking of my grandparents. They’re the toughest four people I know and that’s what helped me get through that.”

“I think people may be feel bad for me that I’m not winning everything and whatever, but I want people to be more concerned about other things going on in the world, people that are truly suffering. I’m just proud to bring home a gold medal to Team USA. I’m always striving to be my best, to be better than I have been. But it’s not easy when your times are world records in some events.

“You can’t just keep dropping time every single swim. I’ve really learned a lot over the years. The times might not be my best times, but I’m still really happy that I have a gold medal around my neck right now.”

Katie Ledecky – by Patrick B. Kraemer

That word came up again.

Perspective. No longer able to hold back the tears and tremor in her voices, Ledecky recalled some of those she’d met along the way: children hospitalised with grave illnesses; soldiers who’d suffered horrific injuries in battle. She said:

“How their eyes light up when they see the gold medal. That means more to me than anything, that ability to put a smile on their faces. I just really wanted to get a gold medal to have that opportunity again.”

Katie Ledecky – Photo by Patrick B. Kraemer

Ledecky – Paris 2024 Here We Come

Access to “again” means doing what she loves to do – and what she knows to hold hand with pressure, stress, judgment, expectation and a range of other things that constitute a thumbs down if she lets them. Of course, Ledecky has enough medals to take on the trail of inspiration and motivation to come but she’s not done yet. In Tokyo she said that, all being well, she would train on and seek a place on Team USA for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games at the age of 27. Los Angeles and a 2028 home Games at 31 might be a stretch for the distance queen but she’s not ruling it out:

“I’m still young. Twenty four is not that old. People are sticking around in this sport into their 30s. I still love this sport. I love it more and more every year. I feel I’m going to give every ounce I have to this sport. I love the training, I love the day to day. I’m just going to keep doing it until I feel like it’s time. Obviously, the Olympics in 2028 are in L.A. so that’s kind of out there and appealing also.”

Katie Ledecky – photo – queen of the Olympic medallists in the pool – by Patrick B. Kraemer

The competitive urge remains strong and the presence of Titmus may even drive Ledecky to more moments of soaring excellence in the pool. As she put it in Tokyo with a nod to having a rival capable of getting a hand to the wall ahead of her: “She [Titmus] swam so fast at her (Australian Olympic) Trials and I was a little off at my Trials and it really pushed me to work hard for that period in between Trials and here. I wanted to deliver. I wanted to have that great race that we had in the 400 (freestyle). I wanted to be up there with her and give her a great race.

“I think we’ve really pushed each other, not just this week but over the past five years in training. Just knowing that we’re both out there working hard and trying to get to this point and get to these races.”

Online Mental Health Resources – English language

Focus on Athletes and Sport

Mental Health – The Athlete’s Journey

The NCAA Sport Science Institute – Mental Health Educational Resources

Mental Health in Athletes: 45 Resources to Help You Cope (Online MSW Programs)

“Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps, NBA player Kevin Love, tennis champion Serena Williams and UCLA gymnast Katelyn Ohashi have captivated sports fans with their athletic abilities. They are also among the sports figures who have spoken openly about challenges with mental health. Elite athletes in the spotlight for mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders and PTSD, give a voice to others who quietly face the same struggles and remind everyone that even those who perform seemingly superhuman feats struggle sometimes and need support.”

MSW

Google Scholar links to mental health resources with a specific emphasis on athletes and sport

Focus on coaches and coaching

Mind – Support for coaches and physical activity providers

Mental Health in Sport – Coaching Association of Canada

UK Coaching – Mental Health Awareness for Sport and Physical Activity+

A Balance Of Mindset And Mental Health

General

USA – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

AUS – Mental Health Australia

GBR – NHS and charity resources