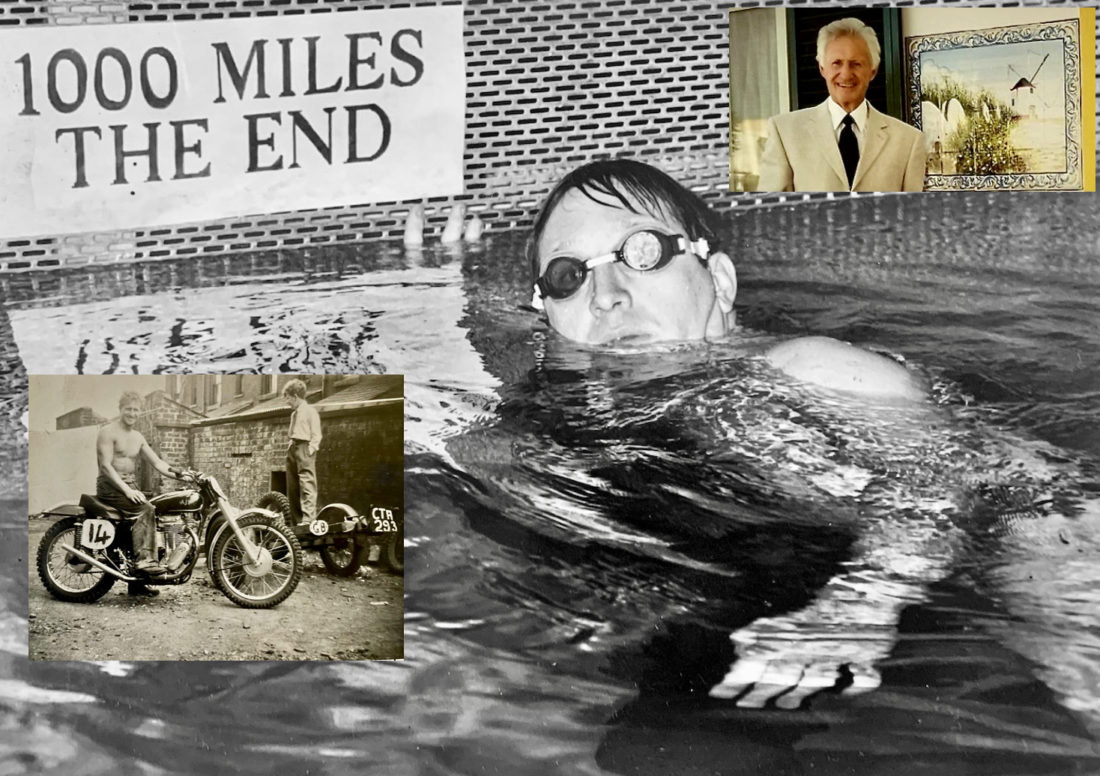

In Mourning For Our Swim Teacher, Coach, Mentor, Husband, Dad & Granddad, Wally Lord (January 2, 1935 – May 19, 2021)

The saddest of days and the hardest of words to write: Wally Lord, the man who taught my sister and me to swim, has swum his last lap in this life. He also happens to be our father; he gave us life and our love and understanding of water, our sense of fair play. He was our feet on the ground; our whistle on the deck; the daily bread of our formative years and an anchor of perspective and good humour throughout a life stretching across nine decades, from the restrictions and rations of the war-torn 1930s to the confinements of a pandemic and ailment of the past two years.

He will be sorely missed, not least by our mother, his sweetheart since they met 70 years ago. He was 86 years, 138 days and a few hours old at his passing – and he used his days well for as long as he was able. What follows is a ripple of the swimming context of a long life well lived.

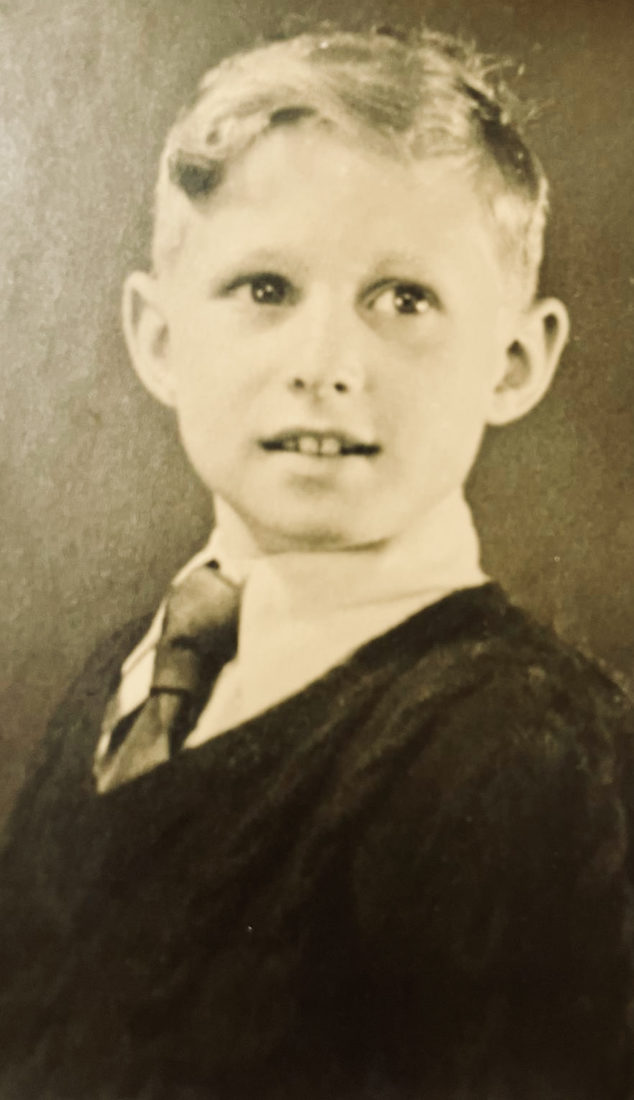

Born in the damp and smoggy industrial north-west of England on the cusp of the Second World War, he developed a chesty cough as a child and a doctor recommended to my grandparents that they take their son to learn to swim because swimming was a cure of cures, a medicine for life.

So it proved. Swimming also became his anchor, his passion, his fitness and a professional pursuit that stretched from baths management to teaching, life-saving, water-polo, coaching and helping others bring out the best in themselves.

He spent the bulk of his life infecting people with enthusiasm, insisting on honesty, knocking bureaucracy, amateurism and other forms of pettiness apt to hold folk back, imparting his knowledge of swimming skills to generations and showing them what they could be beyond what they thought they could be. He believed that hard work and “fun” were good companions and that the discipline, dedication and determination he came to better understand during military service in the Royal Air Force could be put to use in sport not only to help young people be the best they could be at their chosen activity but be the best they could be in life at large.

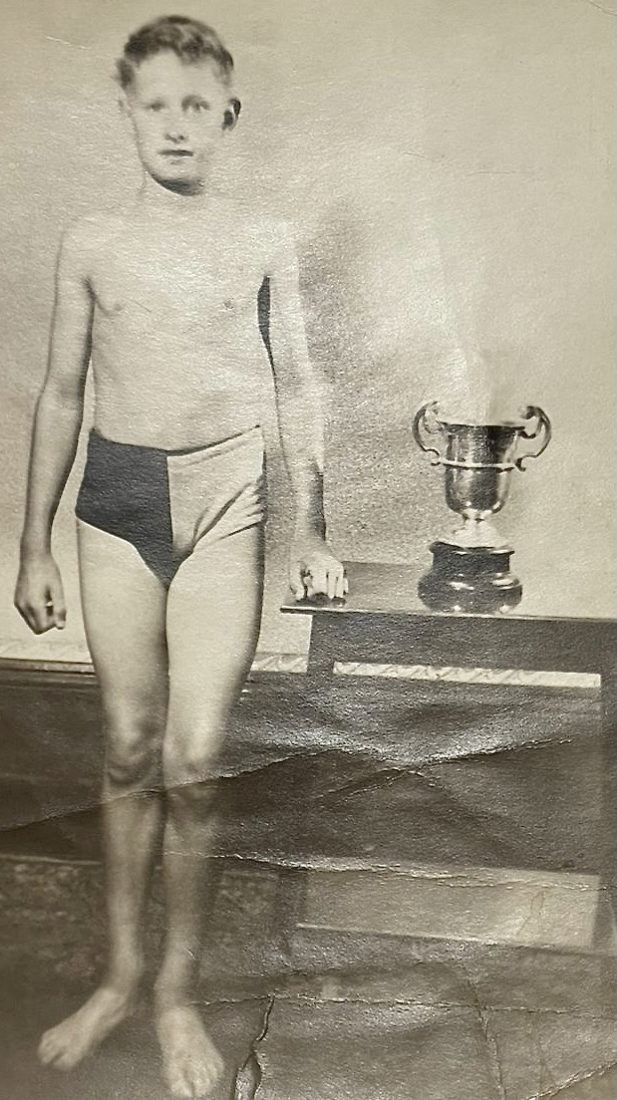

After learning to swim, he joined the local Radcliffe Swimming Club. Aged 12, he won his first regional-championship trophy, racing in woollen trunks that soaked up the element and served as a friend to drag in the days when a suit was the very foe of streamlining, angles of buoyancy and at-oneness-with-water.

A schools champion in the North-West, he was also keeper for Radcliffe Football Club for a few seasons and trained to be a King’s Scout in the reign of King George V. The award and rank of King’s Scout was given to senior scouts “who prove themselves able and willing to serve the King, should their service at any time be required by him.”

The lesson of ‘what you put in, you get out’ learned in the pool, was reinforced in the scouts by the need for dedication and discipline, as well as a requirement to pass three efficiency tests in the following skills: Ambulance, Marksman, Bugler, Seaman, Cyclist, Signaller.

He passed and was selected to be a King’s Scout at the 7th World Scout Jamboree in Bad Ischl in Upper Austria between August 3 to 12, 1951. All King’s Scouts received a personal message from the King, signed by his facsimile signature. Dad’s was signed by King George VI, who passed away in in 1952, after which Queen Elizabeth II, the reigning Monarch, ascended the throne. That timing meant that our dad remains one of the last King’s Scouts before the honour became “Queen’s Scout”.

More than 60 countries took part in the 1951 Jamboree, the glimpse of cultures, the sound of languages, the friendships formed sparking curiosity and wanderlust in a boy who would spend almost all the days of his life rarely sitting still.

The end of school at the turn of the 1950s meant work for most. What to do? Apprenticeships offered pathways into trades and professions and his father (our grandfather), the foreman at the town’s paper mill, suggested he try out at various places to see “what you fancy”. A trial at a joiner’s firm was up first. It was short-lived and marked by two notable episodes. The North is known for rattling the naivety out of the native fairly early on.

On his first day of making tea and running errands, he was sent for “a long stand” at the local hardware wholesale store: he asked, got a nod and then he stood a very long time indeed before realising the joke was on him and it was time to go home. Unintentionally, he repaid the joiner in kind when it came to time wasting. He was asked to nail planks to a series of beams on a housing project. When he was done, the foreman called him down to the ground floor, shook his hand, said ‘well done, brilliant’ before pointing up to a ceiling pitted with hundreds of nails just the wrong side of the beams they were intended for.

It wasn’t for him. He liked to know how things worked and if they didn’t why and how he might fix them. He rebuilt and fixed his own motorbikes and would later build a pocket bike from scratch for my sister and me to buzz around on as kids. Mechanical engineering became his subject and that pursuit was nurtured during his National Service in the Royal Air Force.

Soon after arriving at the RAF base he’d been assigned to at Middle Wallop in Hampshire, his squadron was told to be outside the medical centre the following dawn. There’d be some travel and they all needed vaccinating against the likes of Smallpox (at a time of mass outbreak), Diphtheria, Tetanus and Yellow Fever. Early on in the current pandemic, he retold a story I’d heard several times down the years.

“The door of this long shed-of-a-building opened and we were just fed through, a jab in one arm, move along, a jab in the other, bend over for a different jab, then swig this down with some water and so it went on. You then had to walk to the other end of the shed and through a door and there they all were: piles of bodies of the blokes who passed out from it all.” A pause of northern-comic proportion followed, as was often the case with dad, before he said: “They were alright: there wasn’t one of ’em missing for dinner.”

There was “one of ’em missing” one morning at dawn-bugle roll call. In fact, there was a whole bed missing from the dorm. It – and the sleeper in it – had been carefully lifted out of one window, its legs tied to the wall with ropes secured though two windows at a height of several feet off the ground. Thankfully the sleeper’s alarm at waking didn’t shake him out of bed. He was helped down; no-one admitted to it; the entire squadron paid a price.

Dad would never say if he’d had a hand in it. His discharge papers, which mum has to this day, suggest he’d either been blameless or had learned valuable lessons at Middle Wallop. A commendation includes the line: “Conduct – Exemplary”.

The RAF nurtured two callings in him: his love of engines and his love of fitness and physical education. They would both play an important role in the pathway of his life, most of which was spent with the woman who would become his wife for 63 years.

At the time he got his call up, dad had his eye on two girls, one at the swim club, the other in the next town, both called Joan. The other would become our mother and during his years at the RAF he would send love letters home along the length of the used ticker tape ‘borrowed’ or discarded by communications operations and the air-traffic-control tower he would sometimes work in.

“He was a devil,” mum recalls. “He’d write the whole thing from the very inside outwards so you had to unravel the whole tape to be able to read it. Some of ’em were yards and yards long.” Apart from the odd weekend home, they rarely met during those years, much spare time taken up by fixing bikes, “messing in engines” and military swimming competitions held in pools and sometimes lakes the length and breadth of Britain.

Towards the end of his RAF service, dad made a mistake, one that meant that my sister would be born and I would be here to write this: he sent a ticker tape love letter to the wrong Joan, who noticed it wasn’t meant for her. And that was the end of that. One girlfriend it would be.

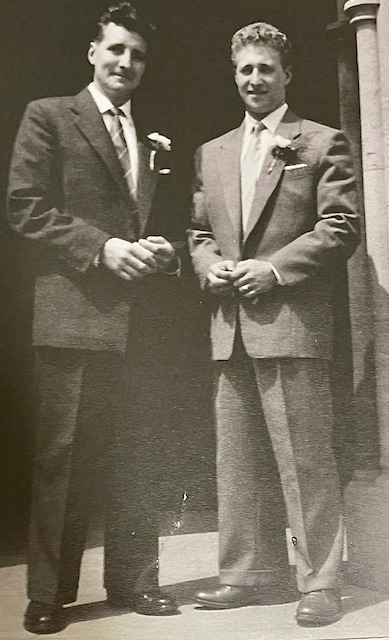

It would be the one whose green beret he’d pinched while showing off by swinging Tarzan-like from a rope tied to the rafters of a bridge and leaping several metres down to the river below. A time of swallows, amazons – and, as ever with boys, peacocks. Our mum-to-be had been given the beret along with a matching coat as part of a Catholic tradition of getting something new for Whitsun. The eyes had it – and seven years after they’d first gone out dancing on a date, when dad was 16 and mum 15, they got married. It was 1958, by which time, dad had furthered his career in mechanical engineering.

An apprenticeship included a spree in Germany, where he trained alongside others in some of the first work and education exchanges between Britain and Germany in the wake of World War II. The experience would reap dividends in the years ahead when he came to apply his interest in and love of innovation to his work in sport.

A Dad Is Born

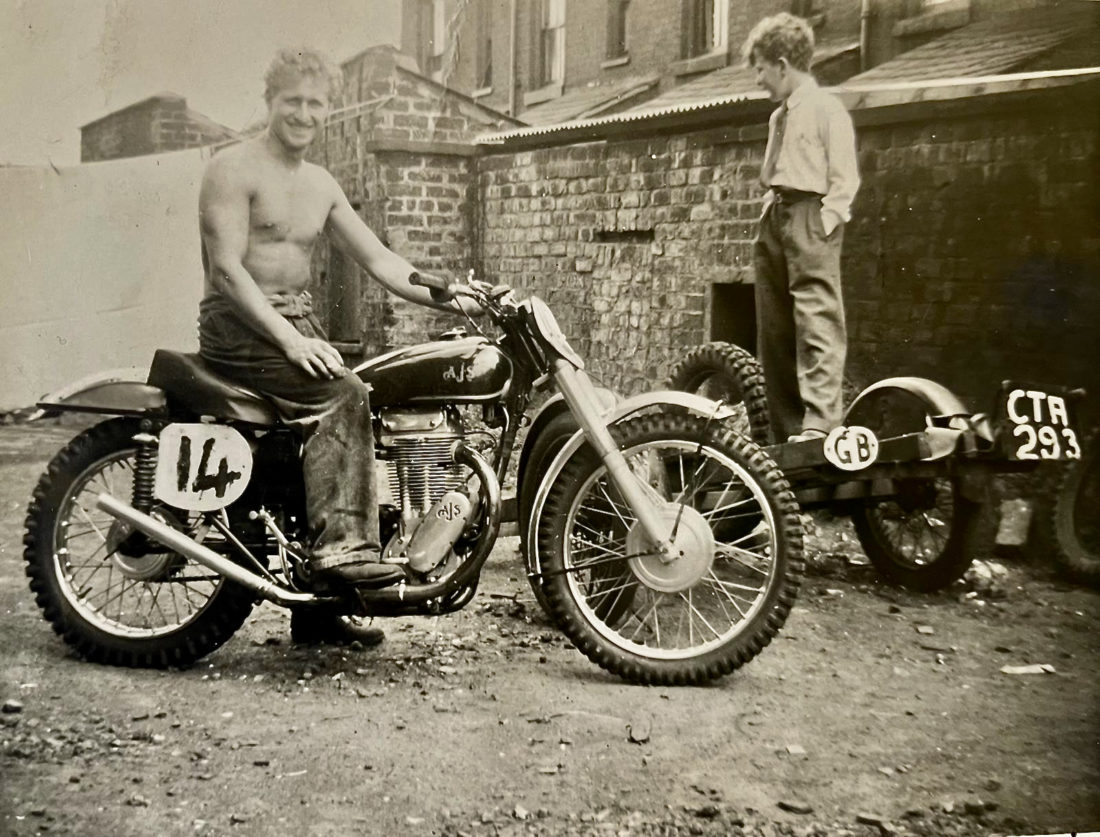

On return home, he set up a business running his own garage, fixing cars and building bikes. That’s where he was to be found when my sister Deborah was born in 1960 and when I followed in 1962. He took up scrambling, bought a trailer and tuned his own bikes ready to race. He competed in Isle of Man TT (Tourist Trophy) races, among many others, and met Steve McQueen as the American made his way to Erfurt for the 1964 ISTD.

All the while, he served as an assistant teacher and coach at Radcliffe Swimming Club alongside the volunteer head coach Billy Pearce Snr. It would not be long before water became a greater passion than oil.

At the club, Pearce’s son, also Billy and bound for a working life as a policeman who for many years specialised as a frogman, and several other big blokes who trained in the pool, played water polo and enjoyed a pint or two together afterwards. They needed a goal, it seemed to my dad.

Coach To A Crossing: Swimming The English Channel In World-Record Time & A Change Of Stream

In the early sixties, he persuaded his squad of men to take on open water, with races in lake, up canal and out at sea in places like Morecambe Bay, where the challenge of chilly waters is matched by tides fit to fool any but the most experienced of boatmen guiding swimmers: depending on what time of day and the weather, among other factors, the fastest course was often the longest route, the smart swimmer the one who swam out and got swept back in, not left fighting against the current as exhaustion set in towards the end of the fight.

The goal that tempted the men into such waters was the English Channel. On Sunday, June 17, the team was made up of Billy Pearce, Arthur Marshall, Dave Dewsbury, Tony Heaton, Stuart Pickup, and John Stanistreet endured atrocious weather and accompanying swell, conditions that added an extra eight weary miles to their ordeal, to set a World record relay time of 9 hours and 29 minutes. Reserve swimmer Barrie Middleton was not called upon to swim but his role in preparation and support forever made him a member of that team.

In its report of the achievement, the local Bury Times reported Heaton as saying:

“We are naturally thrilled that all the training we have done since Christmas has been worth doing, but this is something we could not have done without Wally Lord [trainer] and Bill Pearce Sr [manager]. Wally has pushed us to the limit at times and we have sat down and wondered whether it was all worth it. Now we are sure it was.”

Tony Heaton – image – The World-Record Breaking English Channel Team From Radcliffe Swimming Club – cutting courtesy Bury Times

The report also read:

Triumphing over a choppy sea and an almost unbroken blanket of heavy fog, the Radcliffe Swimming Club long distance team slashed 29 minutes off the English Channel relay world record.

Despite the difficult weather conditions that added an extra eight weary miles to their ordeal, the team completed the challenge in nine hours and 29 minutes on Sunday.

But for the fog and their wide deviation from the shortest route, the lads would almost certainly have beaten the world record by two hours and experts described their performance as “magnificent”.

For much of the swim, the team were surrounded by a drama they knew nothing about, as two lifeboats and an RAF rescue helicopter searched the water on Sunday morning, following reports of distress calls.

It was, in fact, team members cheering on their teammate Arthur Marshall over the loud hailer as he raced towards the Kent coast.

The team only learned of the search and radio newsflashes that had raised anxiety among friends and family once their escort boat drew into Folkestone harbour.

News of their record-breaking time came through on television that evening and was greeted with huge cheers from the crowds gathered at the Swan Hotel in Stand Lane.

The Mayor, Cllr J Lomax, said: “I am delighted with their success, particularly as everyone was so upset by early news that the team might be in difficulty in the channel.”

Fifty five years later, the swim remains the 79th fastest time out of 1,097 relay swims ever undertaken across the Channel.

All those years later, too, Billy Pearce recalls:

“Wally’s RAF service really improved his fitness for P.E instruction and that combined with his thirst for knowing how mechanics worked and how you might improve things and make them better and faster helped make him the terrific coach he was. He applied it to equipment he’d build for us to train with and he observed what the water was doing and how that affected how we swam. He was streets ahead of anyone around where we were: he taught us about acclimatising for different conditions, had us sitting in cold baths, got us doing weight training to improve strength, cross-training with running and other sports at a time when those kind of things were not a part of swimming in general. If he’d been an American, they’d have picked him up as a feted coach.”

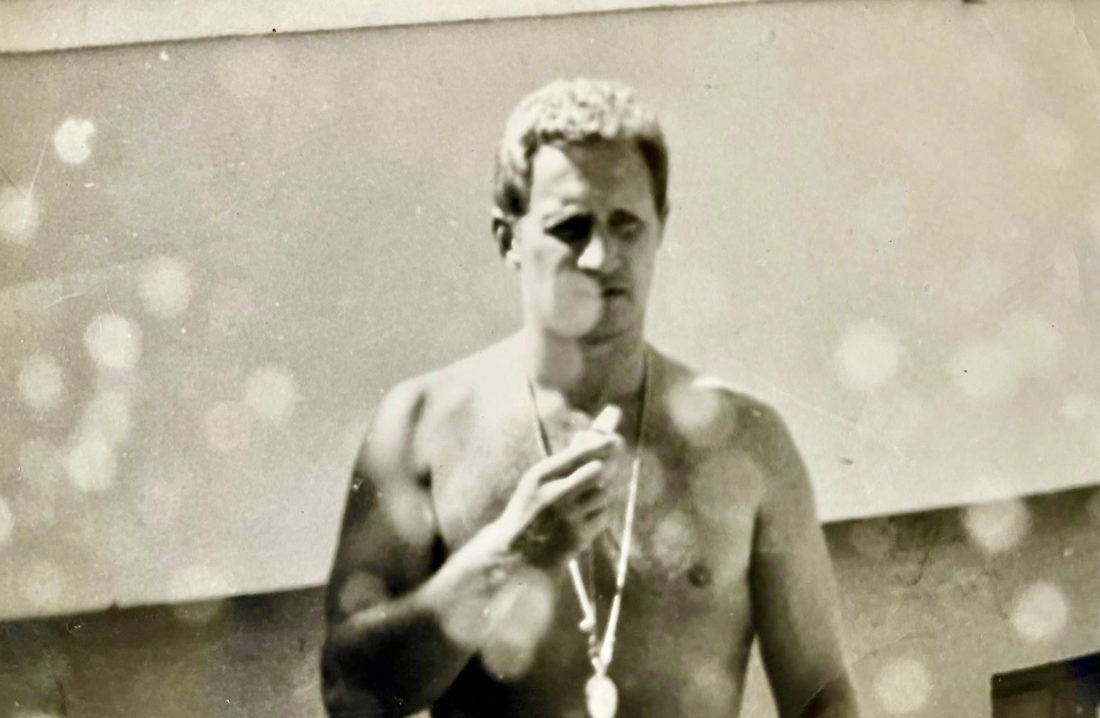

Billy Pearce – image: Wally Lord in his 20s, his scrambling hobby taking over the backyard

Being an innovator isn’t all plain sailing, especially without a budget. Our mother came home from shopping one day to find water running down the stairs in the house. The bath had been filled with cold water and the big blokes had been instructed to take turns at seeing how long they could stand it with no grease on. They were all thrown out and the coach shown a red card.

Through the years, dad would build his own dryland equipment, including swim benches and pully systems when programs simply didn’t have the money to pay for the commercial product. He had whole squads make their own paddles from balsam wood, with large elastic strips cut from tubing (and even pant elastic) stretched and overlapping across the paddle and secured four carved-out grooves.

Pace clocks were painted on wooden boards and fitted with kitchen clock mechanisms that turned the hand-made hands that set the time for swimmers to go after stop. If, in the welter of excuses that can float across the water in the midst of a hard set, there was a complaint of “can’t see the numbers” or “can’t tell which hand is which”, he’d come back the next day with a bigger, better, brighter version and a sign saying “no excuses – get the work done”. Sessions were very rarely called off. If the water was too cold or the treatment of it unsafe, he would find instant ways to improvise: we’d be off on a run, in a gym or gathered around benches for talks and demonstrations about skills, techniques, the way of water.

After the Channel campaign, he craved more of the coaching and less of the garage. A couple of years on, he applied for a baths management position at Maidstone Baths, got the job and our days in the north were done, beyond the family connections that remain to this day and forever more.

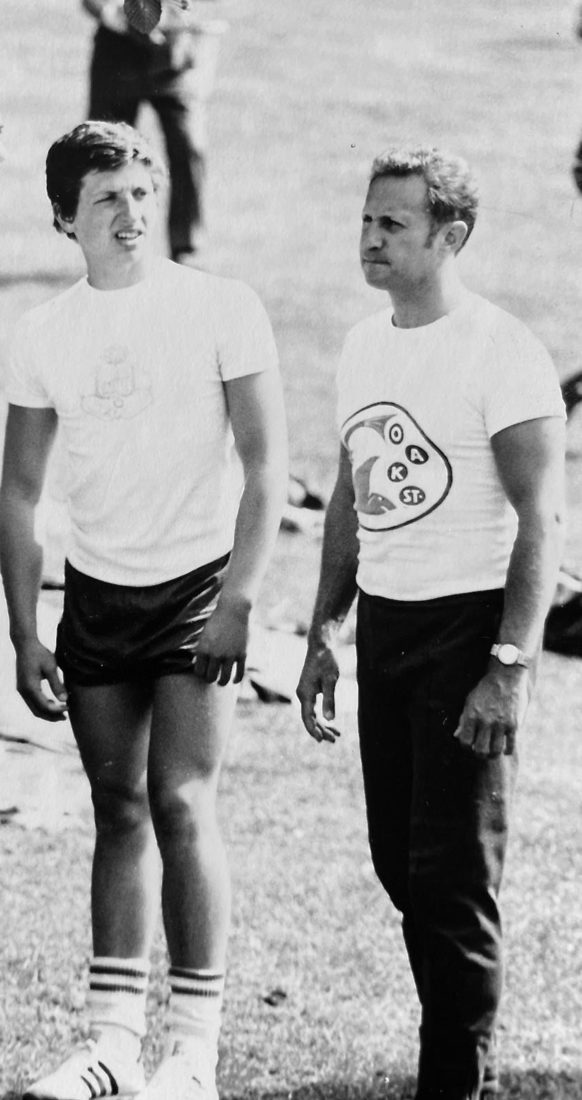

It was a time of learning and soaking up knowledge for dad, who joined national coaching courses such as that he was on in Loughborough when the picture to the right was snapped. He gained his senior coaching qualifications and read everything “important” he could get his hands on. The works of Doc Counsilman, Forbes Carlile part of his font of knowledge and library of learning. Later there were works from Bill Sweetenham, Cecil Colwin and others, book ends for his appetite to know more about the art of getting young folk to be the best they could be, through swimming but in life, too.

He had an office at a Public Baths in Maidstone. It was stacked with swimming magazines that arrived from far flung places around the world like treasure chests loaded with words and pictures I would wallow in. The place still had the baths section where folks would turn to not for a swim but to wash and wallow, carbolic soap at hand to scour their skin before a Turkish Bath would turn them as pink as the soap. There was a pool, too, of course, one with what seemed to me to be very high walls, off which the wash was like an ocean wave. The changing rooms were cubicles all around the tiled, mosaic deck.

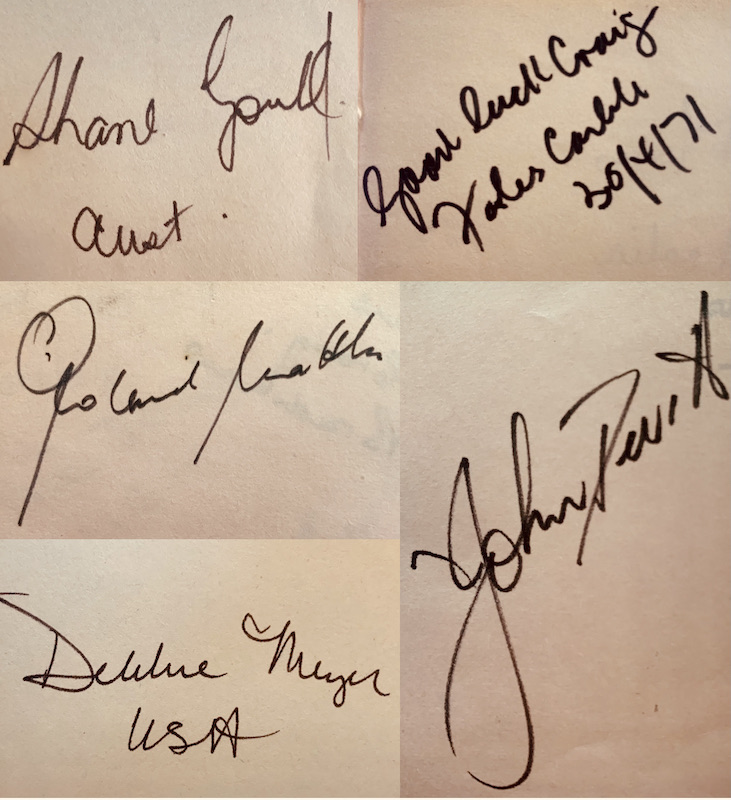

It was while we lived in Maidstone that dad heard the Australian and American national teams, along with many other international squads, were coming to Crystal Palace in London to race at the Coca-Cola Meet. He would never miss such chances and I was lucky enough to go along with him to see Shane Gould match Dawn Fraser‘s 100m freestyle World record; set the World 200m freestyle record; meet Forbes Carlile; have a giant (to the 8-year-old me) called Roland Matthes lift me high into the air and swing me round; fill the autograph book my mum had bought me especially for two big days out so that I collect all those names I’d read about in the magazines from Down Under, from across The Pond and Channel.

The book is graced with the signatures of Australians Gould, John Devitt, Karen Moras, Debra Cain, Americans Debbie Meyer, Ross Wales, Alice Jones, Germany’s Jutta Weber, Hakon Iversen of Norway, the entire British team, including Kev Burns, Canadians Bryon MacDonald, Donna-Marie Gurr, Angela Loughlan, who was coached by Nick Thierry, the founder of Swim and SwimNews and father of World Rankings with whom and for whom I would one day work. There were notes from Americans Rick and Lynn Collela, and, among many other ‘best wishes’ a “Good Luck, Craig” note from Forbes Carlile, who I would not meet again until a few decades on as a journalist but whose works I knew of through the books and lore that dad handed on like a constant flow of gifts.

All of those folk, fast, impressive and some flawed, and many others dad would speak to his swimmers about. He sought to make them understand what it took and how they, too, “with two arms and two legs, a heart, a pair of lungs and a mind to get the work done” could and would go further than they might have imagined, in the pool and in life, at whatever level, Olympic to local club and community. He knew it because he’d done it himself.

In Kent, he founded the Mote Park Swimming Club, which later became assimilated into Maidstone Swimming Club, which had been formed in 1844, is recognised as England’s oldest competitive swimming club yet, but in the late 1960s had got stuck in a rut and needed a competitive jolt. The club is now based at Mote Park in a leisure centre built long after dad had whisked us all of on a life-changing adventure.

A Lusitanian Love Affair

He had two job offers: one was to run a Baths and its swim program in East Kilbride in South Lanarkshire and in 1947 designated Scotland’s first ‘new town’. The other was to head south to Lisbon in Portugal to be head coach at one of the country’s top three clubs, Algés e Dafundo. You can read more on aspects of that journey from my perspective in this reminiscence.

The memories of the people we met, the friends we made are far too many to recall here but they add up to a Lusitanian love affair. Portugal was, remains and will always be a home from home for our family. We spent just under a decade there. For me and my sister, those were formative years: we learned the language not just of words but the weather of its humanity, its heart and soul, its way of being, its nature, food and the culture of a country that went from dictatorship to freedom on one fine day, April 25, 1974, as described in my memory of Algés.

There were many swimming journeys the length and breadth of Portugal, in the old Algés club bus, on which I learned the Portuguese of Portugal, complete with folkloric songs, some with lyrics best not repeated. For my dad, and mostly my sister, who made many a touring team on her way to representing Great Britain at the World Student Games, the European competition circuit of meets in Germany, France, Spain and Switzerland, such as the Geneva International – all still up and running – took them far and wide on many occasions with Portuguese squads. His swimmers raced onto scores of national teams, including the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal, at which he served as a team coach and got to witness the first wave of the GDR women’s Olympic dominance at first hand. The memories and souvenirs he brought home live on in and with us.

After Algés, dad accepted a job offer to lead the swim program in Oporto in the north of the country and Paulo Frischknecht joined us there to prepare for a 1976 season in which he would make the Olympic squad for Montreal at the age of 15 a month before becoming the first Portuguese swimmer ever to make a European Junior-Championship podium, with silver in the 100m freestyle, 0.12sec shy of gold. Paulo would go on to race at the 1980 Games in Moscow and would later become president of the Portuguese Swimming Federation and the first Portuguese member of the FINA Bureau, for a short time before petty politics of precisely the kind my dad so hated, saw Portugal shoot itself in the foot. Paulo served as the Director of LEN, the European aquatics federation and is now Chairman of the Board at the Portuguese Sports Foundation and a Member of the National Sports Council.

Dad’s move north further sharpened the competitive edge in Portugal, where a few programs competed for just about all the prizes and honours going. During his years in Portugal, dad raised the game for all those programs on a number of levels: work ethic, workload, working as a team all for one and one for all. Other clubs would send people along to watch and learn from “O Mister” (The Mr. said ‘Meeschter’), which is the name they called him by, so much so that shouting out ‘dad!’ from the end of a lane during a set often went unheard, his ear only tuned in to “Mister!”.

The Porto program, where dad coached Teresa Figueiras, to this day the Portuguese swimmer with the record of having broken more national swim records (263) than any other Portuguese swimmer, was linked to the FC Porto, where crowds would gather on a Wednesday each week as “superstar” players arrived to collect their weekly wages. There were no barriers and the fans would cheer as each player arrived, leaning in to touch an arm, a shoulder, shake a hand if they were lucky. There was a touch of worship and religious ritual about it all. The money generated by football would feed into the rest of the club and support myriad other sports, swimming included.

The friends we made then, remain friends forever. Special mention in Oporto is reserved for Antonio and Leonor Feio, who embraced our family, took us to landscapes and restaurants and experiences off the beaten track and deep into the heart of the north of Portugal. To this day, all these years on, we feel at home in Portugal, a part of us having never left.

Antonio and Leonor’s daughter Isabel swam in the youth lanes alongside me and the likes of the twin sisters of Paula Andrade (RIP), Teresa and Joanna, Paula Santana, Vasco Sousa, Jose and Rui Borges, who would all become national team coaches (Rui will serve as head coach at Tokyo 2020 should the Games go ahead in July this year after the delay caused by the Covid-19 pandemic).

Scotland Calling – The Next Chapter For Dad

Post-Portugal, we headed to Aberdeen, where the city wanted a swim squad to be proud of. It got one. Heading from a Portuguese summer to a Scottish winter was something of a cultural shock but then the good folk of Grampian did much to make the climate warm-hearted.

We trained out of several pools, including Bon Accord Baths – the link to a piece I wrote about the pool with a few tales from the trail. Dad had an artistic eye; he liked to draw and sketch and paint and he created the logo for the new City of Aberdeen Swimming Club. The program prospered due the work of all, including parent and board and council backing for a focus on squads at various levels, including those at the top end of performance.

Dad’s work there helped to put Aberdeen on the Scottish Swimming map: indeed, the British one, when the team finished second on points at the National Club Championships. Top of the heap among the many who made Scotland and also Great Britain teams was Neil Cochran, who at the 1984 Olympic Games earned two bronze medals, in the 200m medley and the 4x200m freestyle with GBR mates. There were also Commonwealth bronze medals for Scotland in the 4x200m free (1982) and 200m medley (1986), gold in the 200IM at the Universiade in 1987 and silver with GBR mates in the 4x100m medley at the European Championships the same year. I like to think all that pace-setting I did in training contributed … but Neil and his work with dad get at least 99.9 of the badge of merit :).

When it was time for Neil to move on to college in the United States, dad helped in the process, delighted that such talent would be moving on and up. Dad’s work with Neil, as well as my sister, Mike Peyrebrune, Duncan Cruickshank, Allie Hamilton and others, earned him a place in the British Swimming Coaches Hall of Fame.

It was during his time in Aberdeen that Wally Lord was asked to run a swim clinic for FINA in Tanzania. He arrived to find a pool, of sorts, but with water deep green in colour and not in any fit state to ask swimmers, unless for the scaly, big-toothed predator type, to swim in. He spent his time showing the locals how to treat the water in a safe way so that swimmers could swim. On the third day, the water finally cleared and many hundreds of people came from far and wide to wonder at the sparkling pool that was once a swamp that confirmed the worst fears of those whose best advice to their children was ‘never go in the water’. Dad treasured his days in Africa, where his brother George lived for many years (when we lived in Kent, my parents once got a note from customs saying that a lion cub had been delivered as a birthday present for me. I was very keen but, sadly, the cub was sent off to a zoo).

There are too many memories of the fun and motivation dad brought to the job with him each day with a strict edge of discipline he asked to be a daily habit for any who walked through the doors of the pools he worked in.

On hearing of dad’s passing, Duncan Cruickshank, who represented Scotland in distance freestyle at the 1982 and 1986 Commonwealth Games and went off to college in the U.S., where he has made a life for himself ever since, sent a note that conjured up a lot of fine memories:

“What an influence on my life he was. What a man. Crazy, brilliant, fun. Without his driving me to be a better swimmer (and human) I would probably be in Aberdeen still as a homebody. I remember fondly a trip to Germany, the van ride, his long jokes and laugh … Thank you Wally Lord for having made me who I am. He pushed us and was a great disciplinarian, which I for sure needed. And his making us swim so many events really helped me out in college where some folks were prima donnas … for the Aberdeen kids it was ‘coach said do this, so I can and will’.”

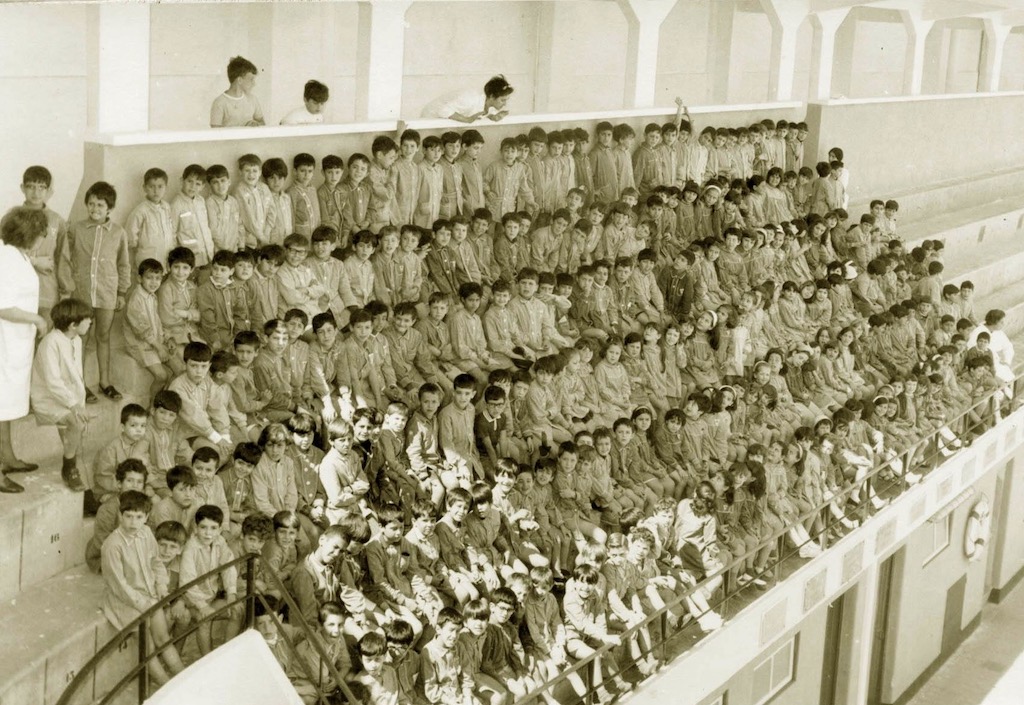

Duncan Cruickshank – far left, sorry for the crop, not mine! 🙂 … and a young Aberdeen team

He recalled one of dad’s party tricks, the squishing of a nose he could flatten to his face (his nose bone was broken and he’d had a part removed many years earlier when a stone span up and hit him in the face during a motocross race). There was the dodgy wiper spray too: when he was forced to use the Lada (built like a tank and in need of handling like one) he’d bought for my mum as a run-around before realising she wan’t up to shifting tanks about, he noticed that one of the spray holes for the wiper fluid was set wrong and meant that the fluid bypassed the windscreen and hit whoever was standing having a chat next to his window. Of course, he called a lot of athletes over to have a last-minute chat before driving off after sessions. There were few days on which he would not combine an insistence on getting the work done with fun, often through the rib-tickling stories he told as often as he could. He had good powers of observation and ability to laugh with not at.

When dad’s tenure in Aberdeen came to an end, he remained in Scotland, taking on the job of head of all baths and pools in Edinburgh, where he also ran the City of Edinburgh performance squad out of the Commonwealth Pool. It was a big job and dad had a fine team of assistants, including Nuala Muir-Cochrane, today one of Britain’s top Masters swimmers and a swimmer who was out there in open water long before “cold-water swimming’ and the like became a health trend and social boast.

The Edinburgh International, still going strong to this day, was dad’s vision and creation. He ran the first editions of it, attracted swimmers from all over Europe and much further afield, Nicole Livingstone, the Australian backstroke Olympic medallist among those who graced the Commonwealth pool at the meet down the years. In the year she raced in Edinburgh, Livingstone topped a podium that included Michelle Smith long before the Irish swimmer’s rocketing rise and fall from grace. Krisztina Egerszegi, Alex Popov also swam at the meet, and Vladimir Salnikov served as manager to one of the first end-of-Soviet era Russian teams to visit. Visitors from all over the world would arrive at the family home, sometimes to my mum’s complete surprise before she took on a Bilbo-esque roll of turning out the cupboards for an unexpected meal and hours of hand-signal conversations that caught things otherwise lost in translation.

The meet also witnessed a ‘comeback’ of sorts by Kornelia Ender, the GDR winner of five golds at Montreal 1976, a Games dad worked at and a coach to the Portugal team and from where he brought back Olympic souvenirs like the door sign I have on my desk to this day. Beyond the fall of the Berlin Wall, she wanted to swim masters and raced a fine 50m freestyle at the Edinburgh International in 1990. The following year, in my third year into being The Times swimming writer, I travelled to Germany for an interview with Ender that was the first in which she spoke about her memories of “little blue pills”, injections and growing out of her t-shirts within three months in the lead-up to Montreal 1976.

Retirement & Return To Portugal

In retirement, dad and mum spent a few years on the south coast of England before following their wish to enjoy some final years in the Portuguese sun. They moved to the Algarve in their 70s and spent the best of their last years back in their home from home.

My grandfather was a keen catcher of trout in freshwater streams and lakes. It was a love that dad had time to return to his retirement but in a different environment. In Portugal many years before, we had often gone swimming at sea, and scuba diving, too. On one swim to a rocky outcrop off the coast in the Algarve when I was about 10, my sister 12, dad indicated “lovely fish”, so we all dived down, only for me to see the tentacle of the giant octopus from hell. To the end of his days, he maintained, quite falsely 🙂 , that it was “the fastest 100m you ever did!” back to shore.

In his later years, he took up fishing on the seafront in the Algarve. Former swimmers and coaches he had worked with decades before would visit my parents from time to time. It meant much to them. And when mz father fell ill, the big sprinter of his day at Algés, José Fuentes Gomes Pereira, was there to provide invaluable help. He’d become a doctor after his racing days were done and my parents talked often about his kindness and assistance at a troubling time.

A more sedentary life in retirement also gave dad time to hone his painting skills. Macular degeneration in the final couple of years of his life robbed him of his ability to paint. He also kept alive his love of making things, carving birds from driftwood and making a doll’s house for his first-born grandchild, Robyn, the only girl among his five grandchildren. He also loved Opera, Puccini his favourite. In the last winter of his life, Alzheimer’s robbed him of his quality of life and many – though certainly not all – of his memories. Last October, he went into a care home for two weeks for an assessment of his needs but because of the COVID-19 pandemic, he never went home. It was only in the last weeks of his life that my mother, Joan, and sister, Deborah, were able to visit him and hold his hand once more.

During the last years and all the more so in the last six months of specific, fraught and draining challenge, my sister provided constant support and comfort to my parents, dealt with the emotional turmoil and bureaucracy of care and in dad’s final days sat with him, sometimes day and night, as his life ebbed slowly away. Being overseas at a time of pandemic has been a challenge for so many families and I was grateful to know that my sister was there to be a tower of strength for my parents, one in a care home ten minutes away from home but visits not allowed.

What will live on long after the torment of a pandemic bruising in so many ways are the rich memories of a full life well lived, for which we, his family, are all grateful.

Wally Lord is survived by his wife Joan, children Deborah and Craig and his five grandchildren.

RIP dad.

If any reading this wish to send personal notes of condolence, please write to me at craig.lord@stateofswimming.com.

In these challenging times, it will not be possible at the moment to hold a memorial service to which all family and friends might be invited. For those wishing to pay their respects, our family has established a JustGiving page for contributions to Alzheimer’s Research UK:

Through his love of life, all things swimming and huge sense of fun, Wally Lord touched the lives of so many people and left us all with marvellous memories and lifelong friendships.

At the end of a long and full life Wally was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. It robbed him of his memories and his quality of life.

In his memory, Wally’s children and grand-children hope you might make a small donation to this world-leading research organisation in the hope that their work will mean dementia, in all its forms, will become a disease of the past.

Thank you. x