Hector Pardoe & The French Odyssey Of A Vegetarian Ellesmere Titan Who Overcame Fear Of Jellyfish For GB Ticket To Tokyo Olympic Marathon

When Hector Pardoe qualified for the Tokyo 202One Olympic Games last week along with Britain teammate Alice Dearing, among well-wishers sending notes of congratulations was an old youth-training mate with a photo of them on a training camp together in Slovenia as 12-year-olds at a time when Britain’s latest swim marathon man was “scared of the jelly fish”.

“He reminded me of when we were going swimming in the sea and how I was scared of the jelly fish and how I couldn’t even put my face in,” says Pardoe, a vegetarian whose voyage evokes memories of The Seaweed Streak, Murray Rose, albeit in water void of the clarity granted by chlorine, walls and a black line guiding your way down the lane.

Pardoe is by no means the first world-class swimmer to feel lost at sea: after double gold (400, 800m free) at the Beijing Olympic Games, Britain’s Rebecca Adlington was asked whether she might have a crack at the marathon one day. She replied:

“I’m scared of the sea. I’m absolutely petrified. It’s the unknown. I can’t stand fish. I don’t eat any fish at all. I can’t. Yuck, can’t stand it. I can’t do fish and I’m petrified of what’s underneath me in the sea.”

Rebecca Adlington – image – Beijing 2008 double Olympic champion Rebecca Adlington and coach Bill Furniss – courtesy of British Swimming

Pardoe, a vegetarian who puts mind over matter when racing, remains firmly with Adlington while on hols but no longer in battle mode. Recalling his recent exchange with that well-wishing friend from his youth, he explains how a Room-101 moment helped him to overcome his fear of what may be lurking in the wash:

“We were talking about how far I’d come, from not even wanting to swim in the sea, to now qualifying for a two-hour race in the sea at the Olympics. If I was just swimming recreationally in the sea, I’m still scared of jellyfish but when I’m in an open water race and I’ve got so much more adrenalin and stuff, I never really think about it. I had a brutal experience with them [jellyfish] in 2018, Malta at the European Juniors: I was at the front of the pack so I was going through all of the jellyfish first and I got some nasty stings all over … I’ve still got a scar from it to this day.”

Hector Pardoe – image courtesy of Team GB

If Pardoe is proud of overcoming his fear of jellyfish, he feels the same about being a vegetarian who tweets about the fishing industry – “Just watched ‘Seaspiracy’ on Netflix, incredibly fascinating and impactful! The fishing industry is a worldwide mafia! Highly recommend watching it”.

Pardoe says: “Being a vegetarian athlete, I’m really proud to be a vegetarian. To be able to compete at the top level in openn water and improve … obviously, there’s a huge theory [that suggests] athletes need protein and natural sources of meat and everything to be at the top level. I just love proving that I can be at that top level and still be on a vegetarian-based diet.”

I ask Hector if he’d heard of Murray Rose. He hadn’t. Quick reminder for those who didn’t know (skip beyond the gold and green if you did):

Murray Rose – The Seaweed Streak

This author was still on a diet of colostrum when the Seaweed Streak (no meat, fish, poultry, refined flour, sugar, chemical-infused foods, but plenty of seaweed, honey and wheat-germ) was racing as a vegetarian on the edge of being vegan to four gold medals at the 1962 “British Empire and Commonwealth Games” at Beatty Park in Perth, Western Australia, in late November that year at the start of a fine southern summer.

By then, Rose was a household name at home and celebrated around the world in the realm of swimming as a triple Olympic champion at a home Melbourne 1956 Olympics and then at Rome 1960 as the first man ever to retain the 400m freestyle crown.

The rest of that history can be read at the foot of this feature

Hector Pardoe & His Marathon Voyage

Hector Thomas Pardoe was just 5 when he started swimming at Whitchurch Wasps in Shropshire. At 20, the Welshman is about to make his Olympic debut, over 10km off the coast of Tokyo in August, his marathon victory in the last qualifier event at Setúbal in Portugal the reward for a decade of regular commitment of swimmer and team at Ellesmere College Titans that culminated in a debut appearance for Britain at 17, followed by a French odyssey with coach Philippe Lucas in Montpellier that helped lead to the ultimate ticket in the sport.

The last-chance-selection saloon in Setúbal featured 98 of the world’s top distance swimmers from all five continents and 47 national federations. Up for grabs were 15 places for men and 15 for women, to take to 25 of each gender who will race in Tokyo, the first 10 qualifiers having made the cut by finishing in the top 10 at the 2019 World Championships in South Korea.

Pardoe was third going into the last of five 2,000m laps off the Portuguese coast. He then overhauled Japan’s Takeshi Toyoda and Athanasios Kynigakis for the win. Toyoda was not in the count of qualifiers: Japan has an entry in the marathon (and every other events at the Games) courtesy of being Olympic host this time round.

Kynigakis was matched by Pardoe’s Britain teammate Tobias Robinson, who also swam a a terrific race to finish 5.5sec behind the winner but will not be in Tokyo: nations can only qualify two swimmers for the Olympic marathon is they have two in the top 10 at the first-wave selection event, the World Championships. As such, Matan Roditti, of Israel, was next into the Tokyo race on the strength of his sixth place finish in Setúbal.

After battle, Pardoe said: “Obviously, I’m ecstatic to get the spot but also with the win. I was thinking before the race that I could be a contender for winning but the point was to qualify and that’s what I was focussed on. I can’t tell you have many times I’ve dreamt of this happening. Despite it being a really tough race, with frustrating conditions including strong currents, high winds and big waves, I felt good in the water throughout.”

Pardoe celebrated his win and ticket to Tokyo with a sum-up-the-voyage thread on twitter that took in the emotion of it all, the “brutal” regime of coach Philippe Lucas, in France; the demands of a selection process that only allows two swimmers per country if they’re ranked world top 10, the principles of excellence (you can be world top 10 and 20 and not make it to the Games) at one end and at the other universality, which applies in pool swimming and many other sports, thrown to the wind in the marathon; his respect for teammate Tobias Robinson, second fastest at qualification but as second-best Brit out of Tokyo; his thanks to Montpellier and France.

The thread ends with this:

“Also special thank you to @coachbircher [Alan Bircher], I would not be the swimmer I am or even involved in open water if it wasn’t for him can’t wait to be in Tokyo together!”

Hector Pardoe – image, Alan Bircher, courtesy of Ellesmere College Titans

Pardoe’s home coach, Alan Bircher, of Ellesmere College Titan, had celebrated his own victory a the same venue off the Setúbal coast, Portugal, back in 2006 when he claimed gold at the World Cup there that year. The prize was season points back then.

For Pardoe, it’s an Olympic debut in the marathon, which joined the Olympic program as Bircher was making the transition from elite swimmer to elite coach. Pardoe will share his first Olympic experience with Bircher, a Britain Youth Coach of the Year honouree who will be in Tokyo as the Team GB open-water head coach.

Pardoe trained under Bircher’s guidance from the age of 11 until he left Ellesmere College Titans for France aged 18 in 2019. In his first season at Montpellier with Lucas, Pardoe became the first British swimmer to race inside 5 hours over 25km. He set the record at the French National Championships at Ile de Loisirs de Jablines-Annet. In 4 hours 59mins 3sec, Pardoe took down Bircher’s British standard by 5 minutes: one of the finest compliments a coach could ever have from one of his charges. Bircher has set the record when finishing 10th at the 2005 World Championships in chilly waters in Montreal. It was a sign that Pardoe, a World junior podium placer for Britain in 2017, had started to chart the kind of waters that lead to Olympic selection.

Add up this mindset and approach from Bircher, the mantra on his twitter account – “Be careful who you let on your ship, because people will sink the whole ship because they can’t be captain” (not quite the same as the ‘be a radiator not a drain’ that Adam-Peaty mentor Mel Marshall pins to the pool wall … but the parallel is close), with what Pardoe describes as Lucas’ “brutal regime” and you have a hint of the challenge of the chart set for Pardoe.

The ship left port when he joined Whitchurch Wasps aged 5 in pursuit of older brother Alfie: hector now says he was happy for the “competitive vibe” of brotherly scraps to spill into the water: “I wanted to get in and race him. It often ended up in fights and stuff. I progressed quite quickly and I was quite a good little swimmer for an eight year old so then my dad decided that if wee were to be at the top level, the club we were at, with the minimal hours the pool was able to provide, wasn’t sufficient, so he thought it would be a good idea to set up Ellesmere College Titans.”

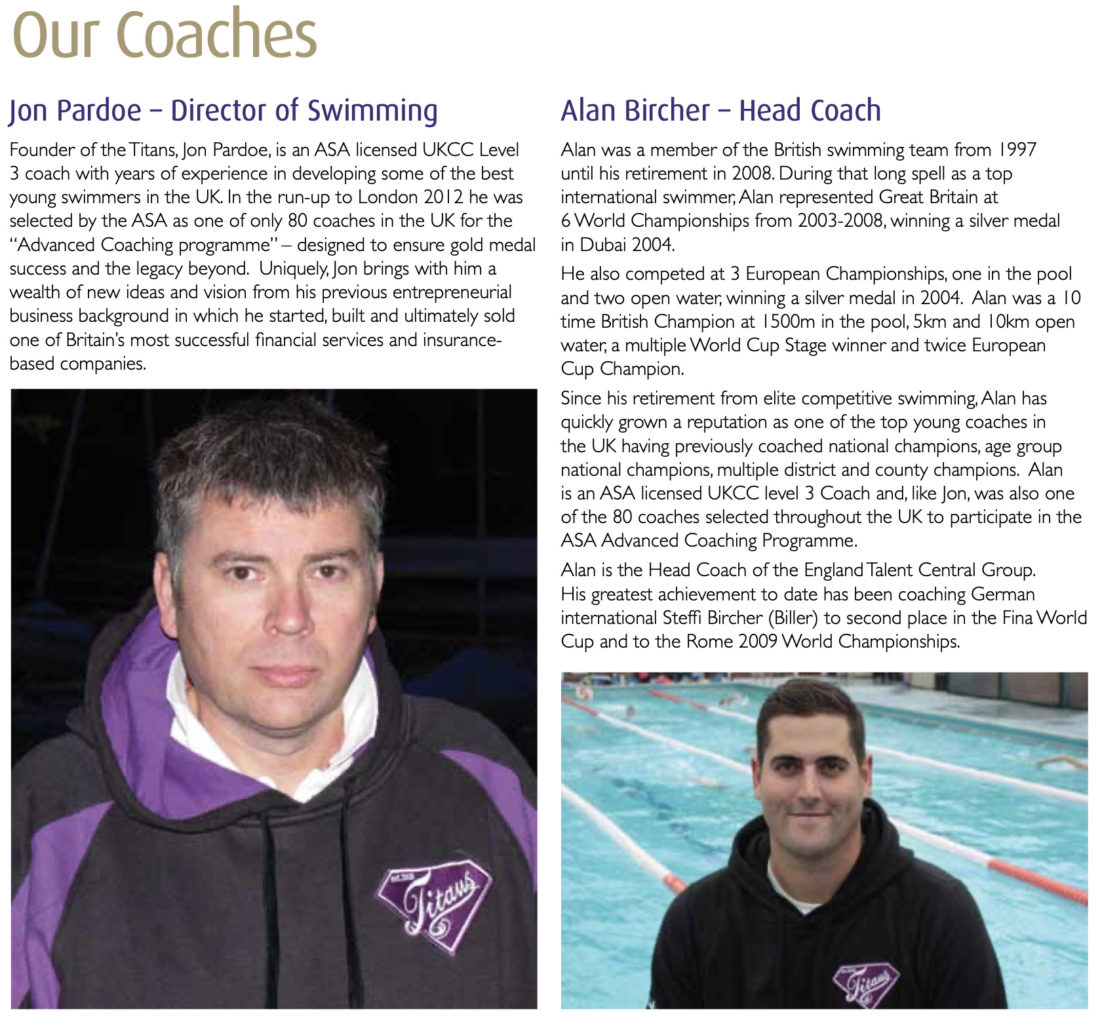

Jon Pardoe, father of Alfie and Hector, was the first director of swimming for the Titans, Bircher the first head coach before he stepped up to be director when Pardoe senior moved on to become Managing Director of the Gee 7 Wealth financial services outfit in 2012.

The Titans program is a collaboration with Ellesmere College in Shropshire, a public (independent/private in international parlance) that offers scholarships to swimmers.

It allows athletes to combine schooling and elite performance swimming. The Ellesmere College Titans started out with the following mindset, one that the program remains wedded to:

“In Greek mythology, the Titans were a race of godlike giants. The Titan Oceanus was the god of the great earth-encircling river, the font of all the earth’s fresh-water. He was depicted as a bull-horned god with the tail of a serpentine fish. In the pool we pride ourselves on being the heirs to this dynasty of giants. The Titans was established in 2008, as a meeting of minds, between Ellesmere College – a school with a great sporting heritage – and the parents of some of the top young swimmers in the North West and West Midlands, united in their desire to create an ambitious, positive and competitive swimming programme.”

Ellesmere College Titans

Pool pride has since spilled into sea, lake and river, courtesy of the young squads that have made a passion of open water, Pardoe winning trophies for long distance racing in the 12 and 13-year age groups. He was encouraged to consider venturing out of the pool by Bircher, who married German open-water international Stefanie Biller, a two-time European podium placer, over 5 and 25km, after the pair met when they were Bath University teammates working under the guidance of coach Andrei Vorontsov. Biller, now Bircher, is the Learn To Swim Coordinator at the Titans, and the couple have a daughter, Poppy.

A few hours after this feature was published, Steffi and Alan had more to celebrate:

Bircher’s own experience in the wash will have been invaluable for Pardoe. The transition from pool to stretches of water with no black line to follow, no sides to hold onto and potentially brimming with wildlife was not easy for a boy to man who admits to a fear of jellyfish. Along the way, Pardoe came to love the open-water challenge, the tactics of the sport and his ability to out-manoeuvre opponents. There’s no gaining 10sec on a rival at the turn in a pool but where one gets it right, the other wrong in open water, a buoy can be a big friend or foe out there on the wave. Says Pardoe:

I was lagging behind in the pool at a younger age. That’s how I got into it and then I just preferred it, the tactical moves, being able to gain 10sec own others going round a buoy.

Hector Pardoe with some of the many medals from his youth – courtesy of Ellesmere College

In The Realm Of The Titans Of Ellesmere

Alan Bircher is one of eight coaches selected by the British Olympic Association to steer the Britain swim team at Tokyo. His focus is open water.

A former World and European silver medalist swam for Team GB from 1997 to 2008, with 10 British titles and two European Cup titles to his name, Bircher has known similar success as a coach: World, European and Commonwealth medalists, national champions and members of the Tokyo Olympic swim team, including Pardoe and Freya Anderson are among his coaching success stories.

For more than a decade, Bircher has helped build the Ellesmere College Titans into one of the top teams in Britain delivering youth talent to the senior program. Millfield and Kelly College were the kind of role-model school-and-sport programs for the Titans set-up established by Jon Pardoe. There’s also Plymouth College/Leander, which has boasted Olympic and World champions Ruta Meilutyte, Ben Proud and Tom Daley as well as GB representative at Europeans Achieng Ajulu-Bushell among its pupils, also have a partnership with Plymouth University, courtesy of the work of Jon Rudd, now performance director to Swim Ireland, and stretches the athlete/academia offer beyond school years.

Bill Sweetenham’s Smart Track program was another vehicle for steering youth talent to senior success: hard to match the hit rate of a one0season selection of talent at the age of 12-13 that ended up delivering more than 25 international podiums at Olympic, World, European, Commonwealth and Universiade levels for Britain and the home countries: that one squad included Jazz Carlin, Fran Halsall, Lizzie Simmonds, Jemma Lowe, Ellen Gandy and Jess Dickons, each a medal winner in international waters, most multi-medal winners at a variety of levels.

Bircher and the Titans are in the league of those programs and schemes that deliver great talent to senior waters in Britain. He noted of late: “I’m passionate about the Ellesmere College Titans and proud of the success the team has had since it was formed in 2008. This includes a minimum of 18 students making qualifying times for the Olympic trials in London 2020 … [including] 13 students making qualifying times for Tokyo.”

Bircher’s role in Tokyo will be that he held for the European Championships at Glasgow 2018: steering the open water effort. It was at Glasgow 2018 that Pardoe came to a big decision. He explains:

“I moved to France in September 2019 and the reason I made the decision was because I went to my first European Open Water Championships at senior level at Glasgow 2018 and got my arse kicked. So I thought I had to step up my training. I’d been training in a small 25m pool. It wasn’t going to help take me to that next level. So I had to find a 50m pool to train in with 25-plus hours and with all the right facilities. I didn’t want to go to Loughborough. I wanted to go abroad, learn a new culture, a language, live by myself.”

Hector Pardoe – image courtesy of the FFN, French Swimming Federation

Pardoe felt that the Montpellier program of Philippe Lucas was where he wanted to be. “He has prestige in open water swimming and is one of the best coaches for getting results,” the marathon ace tells me.

Prestigious results indeed, results that transcend open water: Lucas coached Laure Manaudou to become the first French Olympic swimming champion among women and the swimmer who in 2006 took down Janet Evans‘ legendary 4:03.85 400m freestyle World record that has survived since 1988. Manaudou clocked 4:03.03 two years after claiming gold (400m free), silver (100m backstroke) and bronze (800m freestyle) at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens.

In open water, Lucas coached Sharon Van Rouwendaal, of The Netherlands, to Olympic marathon gold at Rio 2016. The squad is known for covering upwards of 85km in water in training for the bulk of preparation season, with little let-up for recovery times.

Says Pardoe of Lucas: “Though his tactics and approach to getting results is very brutal, he does get the results, so I sat down with my British coach at the time [Bircher] and the director for open water [Bernie Dietzig]. They agreed that that was the best move for me to make.”

I ask Hector to define ‘brutal’ when it comes to Lucas. Workload, attitude, intolerance of laziness or not giving of your best … ? No hesitation, he replies:

“All of that, all of it. Intolerance off laziness, his attitude, how harsh he can be. He doesn’t care about what he says to you or how you feel or whether you’re upset; its not just about strengthening your body physically for open water, increasing your heart capacity, it’s about mindset and never showing weakness in the training. Even if your body feels completely dead and he gives us a big set that we really don’t want to do, if we show any form of weakness he gets really angry.”

Hector Pardoe – images, left, Laure Manaudou talks to coach Philippe Lucas at the 2007 World Championships – by Patrick B. Kraemer – and, right, Lucas

And that applied from arrival day, when Pardoe’s French wasn’t up to subtleties and things might easily get lost in translation. Then again, body language in performance sport is relatively universal, while swimming is awash with internationals from many countries with a strong command of English, as well in the context of the Montpellier squad (among others), French.

Says Pardoe: “I was quite fortunate because he put me in a lane with Sharon Van Rouwendaal and she’s fluent in English and a German girl who was fluent in English and they translated for me and then I quickly picked it up.”

He’d enjoyed the change of culture, the language and food during his French odyssey these past two years. There’s love, too. “In the last six or seven months, I’ve had a French girlfriend who has helped me study [the language] and has helped me with any words I don’t know,” says Pardoe. “Cultural differences with France? I’d say the ‘siestas’ that they have: getting used to everything being closed at 12, then reopening at 2(pm)and then everything, like supermarkets, closing at 8pm, whereas I’m used to the luxury in England of 24-hour supermarket.”

Pardoe will stay in France throughout the rest of this year, after a post-Games break, and in 2022 before making a decision on his future on the way to the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

He hoped that his generation could help make open water more glamorous, rid the sport in Britain of a false impression that open water is “for swimmers who don’t quite make it in the pool”, and also help popularise the sport by lifting performances to where they are in the likes fo Italy, France and Germany.

The line is fine in peak performance: Pardoe is right to point out, especially at a time of Florian Wellbrock, Gregorio Paltrinieri and others excelling in open waters that the marathon is not for the pool swimmer. There’s this, too: Britain was among leading nations at the recent dawn of the Olympic marathon: in 2008, when Beijing held the inaugural Olympic 10km marathon swim and Britain was the most successful nation on medal count, with two silvers and a bronze, won by swimmers with significant pool success, namely David Davies, Olympic 1500m bronze medallist in 2004 before his marathon silver, Kerri-Ann Payne and Cassie Patten, who claimed silver and bronze in the Beijing marathon.

No other nation got more than one medal at Beijing 2008, the golds to swimmers from The Netherlands and Russia in a marathon event in which the USA, swim nation No1, has struggled to mark an impact, Haley Anderson‘s London 2012 silver the only American medal in the 18 handed out since Beijing 2008.

The Definition Of ‘Brutal’

Pardoe may not have heard of Rose before now but he has certainly heard of another great of the sport, the GOAT, in fact, Michael Phelps, whose brand the open water swimmer has worn on his cap in big races, perhaps as a reminder of the American’s “No Limits” mantra.

Worth asking if Hector could described the kind of work with Lucas that had tested him to his limit. “When I tell people that we don’t swim a single session of recovery in the week, they don’t believe it,” he says. “They think it’s not possible. But it’s true, we don’t do a single [session] at recovery rate. Everything is intense. So that’s my definition of brutal. Some people might say doing three or four threshold Vo2 sets a week is their ideal brutal but mine is 10 sessions never stopping, intensity always there, volume is always there.”

Volume and Van Rouwendaal go hand in hand. The Dutch ace last year shifted from Montpellier, where all pools were closed for a time during Covid season, moved to the Magdeburg program of Germany national open-water team coach Bernd Berkhahn, mentor to World 1500m and marathon World champion Florian Wellbrock, among others.

Having recently claimed the European crown over 10km and looks set to have a fine summer in Tokyo five years after a blazing success at Rio 2016, Van Rouwendaal tweets regularly badge-of-honour the distance she has covered in weekly training.

This past winter, it’s often been more that 100km in water, almost all of it in a pool – and not the paddling pool she used for a short while in her back yard when the Covid pandemic first struck.

Pardoe points out that Lucas’ group average 85-95k a week, whereas Berkhahn’s squad tops 100k on a fairly regular basis but that includes recovery sets. Hector notes: “I think our 85-95 week is a lot more intense that the 100k weeks they do in Germany. Danielle Huskisson [Britain teammate] went out to train with the Germans for about four weeks and said they do a big distance in volume but a lot of easy swimming.”

There is a general perception or belief beyond the sport that open water swimmers training in … open water. They do a touch of that but the vast bulk of their work is in pools.

In Britain he had done a charity swim 15km in the Mere, the lake near his school where he learned some of his early lessons in open water, including awareness of environment and water temperature. He retired to the Mere to do a few practice sessions to adapt to the conditions and make sure he could cover the over distance in respectable fashion at a time when his fitness was not where he wanted it to be.

In Montpellier, the Med offers up a giant pool to swim in but all of Pardoe’s training has been in an Olympic pool. He says:

“I don’t swim at all in the sea, which I found most peculiar when I came here [to Montpellier], it being so close to the Mediterranean Sea and the beautiful beaches of Montpellier. I thought that would be included in the training but no: it’s 10 sessions in then pool a week.”

Hector Pardoe – image, on the podium at the helm of Olympic qualifiers in Setúbal, courtesy of British Swimming

Pardoe Primed For Olympic Debut & First Marathon in Asian Waters

When asked about the waters off Tokyo in which he will make his Olympic debut, Hector Pardoe pauses long enough for thoughts to run to controversies related to pollution and high temperatures in a sport that was forced to change its rules following the preventable death of Fran Crippen in a FINA World Cup event off the coast of the UAE.

Two inquiries were heavily critical of FINA and the UAE organisers but despite all that came to pass, several international events run under FINA rules and with FINA observation in place, including a 10km race at the Asian Games, went ahead in waters that exceeded the upper limit of 31C. Teams from Japan, the United States and Canada are among those that have withdrawn from event in protest over officials who faulty to stick to the rules of the sport written with athlete welfare and safety in mind.

Even the upper limit for water temperature (before Fran Crippen’s death, there was no upper limit) is widely thought to be excessive: the upper limit for pool swimmers, including sprinters rocketing down the pool in note much more than 20 seconds, is 28C, yet those swimming 5, 10, 25km and ever greater distances, are expected to be at their best and fastest in waters up to 31C. Ask the likes of Van Rouwendaal, Pardoe and Co, to cover their 100k a week in waters of 31C in a pool and just about anyone you care to ask in the sport would think you’d lost your mind. And yet …

Back to the Tokyo waters and the August marathon Pardoe will race in for Great Britain, the likes of Wellbrock and Paltrinieri among favourites taking on the defending champion Ferry Weertman, Van Rouwendaal’s Dutch teammate.

Pardoe notes that he’s never swum in any Asian waters before He had not heard of any pollution issues with the Tokyo waters but he had watched the Netflix documentary Seaspiracy and seen “how the Japanese go in for mass killings of dolphins and stuff”.

He also knew that high water temperatures have been an issue there, a test event having gone ahead in the face of claims that the waters exceeded the 31C upper limit.

All of which will, as it must, be set aside when Pardoe makes his way to the pontoon at dawn on August 5 in readiness for the 6.30am start to the Olympic marathon 125 years after the first three Olympic races were held in open water

When Sailors Of One Kind Or Another Won The Day At Sea

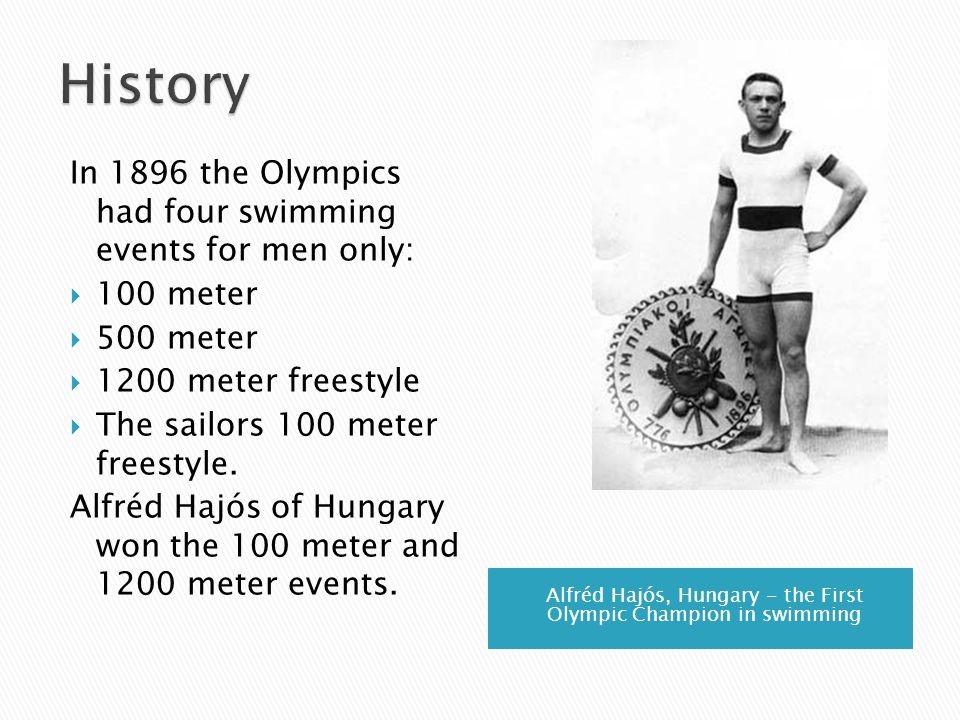

On November 4, 1896, the Athens Games staged a 100m freestyle race only for Greek sailors out in the Bay of Piraeus. The other races had a slightly more international feel to them – and both the 100m and the 1500m were won by Hungarian Alfred Hajós, the distance range of his victories never to be repeated again.

In the 100m, he beat Austrian Otto Hershmann by 0.6sec in an Olympic record of 1mins 22.2. In the 1500m freestyle a little later in the day, Hajós faced 12-foot waves and chilly waters on his way to victory in 18mins 22.2, 2mins 41.2sec ahead of the only other man who made it to the end of the race, Greek challenger Ioannis Andreou.

Hajós, who was born in Budapest as Arnold Guttmann, was 13 years old when he felt compelled to become a good swimmer after his father drowned in the Danube River. He took the name Hajós (sailor in Hungarian) as a sports name because it identified him as Hungarian. He emerged from the swell in the Bay of Piraeus to say that the 100m had taught him to be better prepared for the conditions. He greased up in readiness for the 1500m but the race proved too much for half the field of four and Hajós summed up the battle in terms that sum up a similar mindset to that of Pardoe when overcoming his Room 101 jellyfish:

“I shivered from the thought of what would happen if I git cram from the cold water. My will to live completely overcame my desire to win. I cut through the water with a powerful determination and only became calm when the boats came back in my direction, and began to fish out the numbed competitors who were giving up the struggle. At that time, I was already at the mouth of the bay. The roar of the crowd increased… I won ahead of the others with a big lead.”

Alfréd Hajós

Covid may not allow the crowds to throng on the Tokyo shoreline this time round but the spirit of Hajós will surely be with Pardoe and those racing alongside him come the hour (or two).

More on Murray Rose, The Seaweed Streak…

At what would be his last major-medals event, the 1962 Commonwealths, Rose claimed crowns in the 440 yards freestyle in 4:20.0, the 1650 yd freestyle in 17:18.1, the 4×110 yd freestyle relay with David Dickson, Peter Doak and Peter Phelps in 3:43.9 (ahead of silver won by a Canadian quartet including Olympic and WADA weighty-to-be Dick Pound, 110yd champ in 1962) and the 4×220 yd freestyle with Allan Wood, 2nd in the 440 and 3rd in the 1650, Anthony Strahan and Bob Windle, 3rd in the 440 and 2nd in the 1650 and heading for three golds of his own in 1966.

November 2013 saw the publication of an autobiography by Rose from Arbon Publishing. Life Is Worth Swimming – a forward penned by John Clarke, with an introduction from the late swimmer’s second wife and former ballerina, Jodi Rose, nee Wintz.

From Athens 1896 to Athens 2004, no man was able to win an Olympic crown in the pool at three successive Games, and if Johnny Weissmuller stopped Duke Kahanamoku in 1924 before an underwear contract and the call of Tarzan stopped Weissmuller himself in 1932, then the next nearly man was Iain Murray Rose, with bureaucracy the barrier to his tantalising tilt at the triple.

He might have swum for Britain but that was not to be. Rose was born on January 6, 1939, in Birmingham, England, to Eileen and Ian Rose, as the storm clouds of WWII gathered. A year later, his British parents emigrated from Nairn, on the coast of the Moray Firth at the foot of the Scottish Highlands. They settled in Double Bay, a fashionable Sydney resort with a shark-netted beach at the back door and an inspiring view of Sydney Harbour. That’s where Rose, who attended Cranbrook School in Bellevue Hill, Sydney, learned to swim on his way to becoming on of the greats of the sport.

In 1956, at 17, Rose became the face of the home Olympic Games in Melbourne a month before the Opening Ceremony when he clocked a world record of 17:59.5, becoming the first to race the 1,500m freestyle inside 18 minutes. Rose was dubbed “the Seaweed Streak” courtesy of his specialised diet, which was close to being vegan but not quite. The Olympic canteen could not cater for Rose, and so his parents were allowed to take their son out for meals. Back home, his diet included sunflower seeds, sesame, unpolished rice, dates, cashew nuts and carrot juice, all meals prepared by his mother.

The Rose family traces its origins back to Hugh de Ros, a baron whose name appears as a witness to the Charter of Beuly Priory in 1200. The Iain before the Murray takes a Gaelic spelling in honour of ancestors who fought for Prince Charles at the battle of Culloden Moor in 1746. The family has its own tartan, coat of arms and motto: “Constant and True”.

In Melbourne, Rose, coached by Sam Herford, opened his Olympic account with a relay gold and world record (8:23.6) in the 4x200m alongside Kevin O’Halloran, John Devitt and John Hendricks.

The day after, he raced to an Olympic record of 4:27.3 over 400m, to become the first Australian to lift the eight-lap title, 3.1sec ahead of Japan’s Tsuyoshi Yamanaka, with American George Breen third. Not since Norman Ross in 1920 had a man won both distance freestyle crowns, while no one as young as Rose had ever won three gold medals in the Olympic pool. The tide seemed to turn against the Australian, however, when Breen sliced 6.6sec off the world record (17:52.9) over 30 laps in the third heat, two heats after Rose’s 18:04.1. In the final, thin air could hardly separate Rose, Breen and Yamanaka at 800m. Rose then built a lead of some five metres. With 100m to go, Yamanaka began to sprint. The crowd leapt to its feet, but Rose held on for a 17:58.9 victory over Yamanaka, on 18:00.3, and Breen, who took bronze in 18:08.2, completing a match of the 400m podium. Rose and Yamanaka would later become students at the University of California.

Rose made history again at the 1960 Games in Rome, when he became the first man ever to retain a distance freestyle title, over 400m (4:18.3). Once again, Yamanaka took silver in 4:21.4, precisely the same 3.1sec gap between the two as there had been in 1956. In the 1,500m, Rose, Breen and Yamanaka placed next to each other, but Australian John Konrads, another of European (Latvian) parentage, got the better of them (17:19.6 to Rose’s 17:21.7 and Breen’s 17:30.6). In his career, Rose held all freestyle world records from 200m to 1,650yd, including six standards over 400m (3), 800m (1) and 1,500m (2). His penultimate world record, of 17:01.8 at the US championships on August 2, 1964, failed to sway selectors after Rose opted not to travel home from America for trials. In his absence, the title went to his countryman Bob Windle in 17:01.7.

Rose later married Bobbie Whitby and adopted her daughter, Somerset. His married his second wife, ballerina Jodi Wintz, on October 20, 1988, a few weeks after commentating at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. The couple’s son Trevor was born in 1990.

After his swimming days were done, Rose went on to be an actor, sports commentator and marketing executive. During the 1960s, he starred in two Hollywood films and made guest appearances on television shows. He starred in the 1964 surf movie Ride the Wild Surf and in Ice Station Zebra in 1968. He made periodic appearances on Dr Kildare, The Patty Duke Show, Dream Rider, Time Capsule 1932 and Time Capsule 1938.

Rose, who did include meat in his diet later in life beyond his racing days, also worked as an Australian sports commentator for the Nine Network and US networks at seven Olympic Games. Between 1988 and 1994, Rose was Vice-President of California Sports Marketing specialising in marketing, sponsorships and promotions for the Los Angeles Lakers basketball team and special events at the Great Western Forum. He returned to Sydney with his family in 1994 and worked as a Senior Account Director for Sports Marketing and Management, the official marketing agent for the Australian Olympic Committee, the Australian Commonwealth Games Associationand other Australian sports organisations.

An avenue at the Sydney Olympic complex at Homebush was named after him in 2000. Rose was one of the eight flag-bearers of the Olympic Flag at the opening ceremony at the second Home Olympics in which he played a role. In 2010, Rose led a team on a pilgrimage for Military History Tours to Gallipoli and a 4.5 km swim from Europe to Asia across the Dardanelles.

Rose held a number of charity board positions including the Mary MacKillop Foundation and Patron of Rainbow Club Australia, a non-profit charity providing children with special needs the opportunity to explore their abilities through sporting and recreational activities.

He was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in 2000, for services to swimming. In 2000, he also received the Australian Sports Medal and in 2001, he was awarded the Centenary Medal.

Rose died of leukaemia on 15 April 2012 at the age of 73 in Sydney. The Redleaf Pool in Double Bay, Sydney, was officially renamed Murray Rose Pool in his honour, while Rainbow Club Australia renamed their annual event The Murray Rose’s Malabar Magic Ocean Swim, a two-swim program of 1 km and 2.4 km.