Dirk Lange On Smart Evolution Of International Pro-Swim Teams Tailored To The Individual As Chad Le Clos Flies To Frankfurt

Chad Le Clos’ impending move to coach Dirk Lange in Frankfurt offers not only hope of revival for the South African ace a decade after he produced one of the upsets of London 2012 for Olympic 200m butterfly gold ahead of American outer-orbiter Michael Phelps: it may well be the latest significant move in the evolution of international professional swimming programs that suffered a setback in the COVID-19 pandemic.

As Le Clos prepares to turn a new leaf in Germany with Lange and team this autumn (interview with the hauler of 61 international medals for South Africa to follow), I talked to the coach about the move, its prospects, what Frankfurt offers, the evolution of professional programs, the lessons they teach and contributions they make to national programs.

Pro-Swim Programs & Prevailing Backdrop

Swimming home. What does it mean? What does it mean to each of you? For many it means club, college and through to community, to a relative few it may mean national team. In elite professional swim teams (Lange among the first to set up such a program in the 1990s when he was based in Hamburg and Sandra Völker was heading towards a three-podium success at the 1996 Olympic Games for Germany), home has come to mean a place where an athlete from anywhere in the world can tap into global, individualised and tailored expertise, perspective and preparation with one goal to rule them all: personal bullseye, whatever the goal may be.

Chad Le Clos is on the move after a period without a professional swimming home brought on by the pandemic and the circumstances of the Energy Standard pro-swim team. A short but necessary explanation of just one of several places in the swimming realm blown off course by circumstances beyond their control:

The International Swimming League (ISL) is a work in progress that has suffered setback not only because of FINA’s opposition to moves that had the strong support of athletes (still the subject of ongoing legal action in the United States), not only because of the pandemic, but also because of internal barriers to progress: the derailing of a hugely promising format was at least in part caused by over-complication and a failure to listen to a variety of sage voices inside the League and the sport who basically wanted two things: timely payment and respect for swimming-specific (and media/audience/sector-economy) knowledge key to avoiding rapid concept burnout.

There are reasons why the ISL statement “ISL Innovative competition format will attract more media attention and money” has not worked and won’t work until those running the ISL understand more than they have been prepared to listen to on the nature of media, sports coverage and the one thing many of the world’s biggest pro sports and attractors of media attention have in common: simplicity and the popularity of instant audience comprehension of key questions – who won, why and what does it mean.

The evolution of pro-swim teams, the recent development of the ISL and its associated teams, including Energy, London Roar, Cali Condors and all the rest,

Beyond that, there is the illegal war on Ukraine by former FINA favourite Putin, who was granted the highest order in aquatics by Julio Maglione, the Uruguayan ex-president of the global swim regulator, and has since been stripped of honour by both FINA and the International Olympic Committee, organisations that ought never have got that close to any political leader, particularly those ruling by decree or dictatorship rather than e genuine democratic vote of citizens.

The whole sorry history of sports organisations cosying up to Putin was harmful to athletes and coaches, including all who had to compete against a Russian Olympic Committee team at Rio 2016 that included several swimmers towing doping bans, including one that got to race despite having been banned twice.

Other individuals and business were also harmed by FINA’s relationship with Putin at a time when it was in dispute with the ISL run by Ukrainian energy sector boss Konstantin Grigorishin – a man who poured his wealth into swimming, through education and solidarity in a pandemic and funding the Energy swim club’s development and senior elite programs and the ISL itself – and had a few hundred million dollars worth of artwork seized illegally by the former state-police operative now in charge of the Kremlin.

It is against that backdrop that Le Clos and other members of the Energy International swim team found themselves homeless in a pandemic and then in circumstances in which the League placed itself on hold as Putin-controlled troops ravaged Ukraine, her people and infrastructure.

Other pro-swim programs have been affected by prevailing circumstances but not in the same ways because they are built differently in terms of models of funding, chain of command, structure, numbers of participants, facilities, professional support staff and entourage, and so forth.

In different guises you find them on the pro-side of college-linked programs in the United States; In Britain at national centres; in similar set-ups in Canada, Spain, Ireland and elsewhere. Most of the above have included/include international swimmers from several countries. Super Club set-ups in Europe include Cercle des Nageurs de Marseille, run by Romain Barnier, and coach Bernd Berkhahn‘s Magdeburg distance program in Germany.

It’s a good place to start: all those programs have some obvious parallels but also a wide range of differences.

SOS interview

Dirk Lange On Pro Training Groups & Chad Le Clos’ Revival

Could SG Frankfurt become an International pro-swim program, I ask coach Lange. And if so, why and what are some of the key aspects/approaches of the program that could make it attractive to top and top-prospect swimmers from around the world and in Germany?

“I know all the programmes mentioned, but not down to the last detail,” says Lange. “But I do know the principle of professional training groups. I applied this basic principle at the end of the 90s – perhaps as one of the first coaches- with athletes such as Völker, [Mark] Foster or [Therese] Alshammer.”

He explains: “The core of this approach is that all participants may not be paid like professionals, but that the entire programme is governed exclusively by one principle, which is success. Everything that contradicts this goal is eliminated. So it’s more a view of the sport, a guiding principle, that characterises these training groups, where efficiency and relevance are the decisive parameters.”

“Of course, in Frankfurt we have addressed all the hard facts, right up to combining training with living, eating, school, university or job training. But many other places have embraced those things too. We can also back all of that up with the club’s long sporting experience: since 1993, there has always been at least one athlete from Frankfurt at the annual top event. And in terms of my personal record and experience, regardless of the medals won, I have managed to lead at least one of my athletes to an Olympic final in the past 25 years, with the exception of just two Olympic Games in that period.”

Le Clos is looking to return to the Olympic podium at Paris 2024. He’s currently at the stage, after surgery on hi sinuses, of just being able to put his head back underwater for the first time. Out cycling, running and getting back to work in the water with head under in the coming weeks, he will not arrive in Germany unfit but what kind of pathway can he expect to be on in Frankfurt from go through to World Championships in Fukuoka next summer?

“To me, Chad first needs a solid foundation again,” says Lange. “Of course, he has to race in competition because he is a professional. However, it’s no use if these meets interfere with his long-term development. As a young athlete, he already had everything you need to be successful. He was fast and enduring at the same time, had several strokes on which he could show himself at world level. Now there are some building blocks that need to be worked on first.” He adds:

“The point is, an athlete, like Chad, cannot be satisfied with mediocrity. Certainly it has been shown internationally that underwater speed, front speed, as well as toughness in the final metres are crucial. So we will divide his target races into individual stages and consciously target these goals again and again in training until he has internalised every single parameter. In the competition, it is then a matter of putting this puzzle together and implementing it accordingly according to the course of the season.”

“Despite all the innovations that I have stood for in the course of my coaching career, such as the targeted use of Olympic strength training, I tend to be a conservative coach. At the end of the day, the foundation of a successful season for Chad is hard work: repetitions, repetitions and more repetitions. As his mentor who wants to take him back to his roots, I don’t stand for any bullshit, no motivation mambo-jambo, no voodoo spells, no party times. I stand for smart but hardcore training with a lot of speed, good physical fitness and a lot of competitions.”

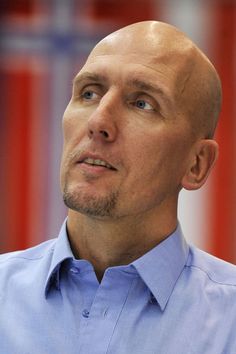

Dirk Lange – photo: Chad Le Clos – by Patrick B. Kraemer / MAGICPBK)

Shared concepts and models abound but the rubber hits the road where we find points of difference. Says Lange:

“What sets us apart here in Frankfurt is what we stand for. It is a smart short- and middle-distance programme that is individually structured and reflects my experience and wishes without any ifs and buts. In a single training session we operate with up to six different programmes to fully develop the individual abilities of each athlete. In Frankfurt, we want success from the president to the coaching team or the physiotherapist – and young motivated athletes who want to line up and race.

“The Frankfurt concept also includes the possibility to train away from home. That’s not really typical of any club arrangement. With Chad le Clos, Oussama Sahnoune, who originally comes from Marseille, or the former world short-course silver medallist and European Games champion Caroline Pilhatsch, from Austria, we have a strong international core of athletes who promote and challenge each other. Our own home athletes are pulled along. It is an added value for the whole region.

Dirk Lange

The “whole region” cuts to the chase on the question of Germany’s underperformance in the pool of late, at least in terms of its potential. There are specific reasons why the country is struggling in the pool beyond the obvious success stories, most of them based with coach Bernd Berkhahn at the Magdeburg distance program and home to Olympic and World champion Florian Wellbrock, his wife and Olympic bronze medallist Sarah Köhler, and European 400m champions Lukas Maertens and Isabel Gose.

Germany has some specific problems that are not uncommon elsewhere, including the ability of swimming to attract enough talent, for that talent to be spotted and supported, for there to be local provision of quality programs backed by the required support (not just for the athlete but an understanding of family circumstances, including the strain that elite sports training can impose on the very home structure that the young athlete relies on as a haven of stability), as well as financial support (regardless of the source, in terms of local, state or national funding and funds generated privately).

Programs far and wide, particularly at a time of tight budgets and the uncertainties and constraints imposed by pandemic and Putin’s war on Ukraine, are struggling.

Lange-led Frankfurt is among those programs that holds the promise and prospect of achieving in sprint and middle-distance events what Berkhahn-led Magdeburg has achieved with the distance group. Is that correct, I ask Lange. “It will only work if Germany as a location is no longer dominated exclusively by the open water and long-distance concept from Magdeburg.”

Questions Asked About Germany’s ‘All-Eggs-In-One-Basket’ Approach

Among critical questions posed by German media, including the influential Süddeutsche Zeitung, even in the midst of Magdeburg’s success story, focus on why Germany has fallen down the ranks of leading swim nations and now struggles to even get relays anywhere close to the podium on the biggest occasions in the sport at global and even continental level.

Some of the criticism, heard from clubs and programs around the country and voiced from time to time in German media, focusses on the distribution and models of financing, subsidies, qualification criteria and annual planning. I ask Lange how he feels in terms of what support there may be in Germany for Frankfurt, among others, to achieve their potential to develop their programs in directions ultimately helpful to Germany’s recovery and progress in the pool. He says:

““If it is not possible to make people understand that 80 percent of the DSV is unfunded and not managed professionally, and that works against them and their best interests, it will be difficult to get Frankfurt or any other location to the place where it belongs. The creativity, experience and responsibility of the individual coaches should be taken into account. This is a question of efficiency and trust.

“Various people in Germany are not unhappy to see short- and middle-distance athletes from Germany go abroad just so that there are not too many different concepts in Germany. Even Wellbrock recently said in an interview that there is no successful concept in Germany other than the long-distance model from Magdeburg.

“Even relay selection criteria at the DSV are currently questionable and incomprehensible. Germany has never been as bad in the field of relays as it is today. And that is wrong. Where are stroke camps, targeted relay measures, bridging camps to guide athletes from the junior to the senior level…? The nomination procedure and the competition season schedule differs significantly in the short and medium distance concept from the long-distance view. Why does Germany no longer have Championships where the winners can be sure that they will be nominated for selection?”

Dirk Lange

Germany is not alone in suffering the consequences of ploughing most resources into the place where success seems most likely to come from. Britain’s recent success in the pool cannot be put down to singular focus of the kind criticised in Germany, given that the medals at 2019 Worlds and 2021 Olympic Games came in a range of strokes and distances and stretched to a very strong showing in relays.

However, at the same time, success in women’s distance freestyle along a continuum of Becky Cooke, through Becky Adlington, Jo Jackson and Jazz Carlin, came down to this drought in summer 2022: not a single England woman could be found in a 400m freestyle final in which 4:15.53 brought the entertainment to a close, nor in the 800m in which 9:13.97 closed the final and 9:30 heats with only 10 swimmers from the entire Commonwealth of nations.

The trouble is not that England has no distance freestyle women but that they have not been listed as being worthy of support, are not supported and, on times much faster than 9.13 and 9.30 are not selected either.

In that sense, Berkhahn and Magdeburg are bucking the trend in distance freestyle when compared to many other nations where much greater emphasis and support is to be found in events up to 200m.

The call for support for distances that cover the full range of relay events is clear from Lange, a man who has led and played a lead role in the performance programs of several nations, including Germany, South Africa and Croatia. Lange says:

“Now even international stars, like Chad, are coming here for the first time. If it is possible to establish and promote other centres with the ‘right mindset’ in the short and medium-distance field in addition to Magdeburg in the long-distance field, then Germany will have a chance to get out of the ‘valley of tears’ in the medium term.”

Dirk Lange – image: Chad Le Clos – by Ian MacNicol

To turn its program around, Germany needs to find more Magdeburgs, and then support them. Could Frankfurt take on responsibility and a leadership role in Germany in sprint and middle distance in the way Magdeburg has for long-distance events, including open water?

Lange believes so. Asked what Le Clos, among others, can expect to find find in Frankfurt at a time when we know something about the size and scope of entourage and the level of support around just one swimmer called David Popovici, Lange tells SOS: “I have been in Frankfurt for one year and during this time we have implemented a short and medium distance concept that meets the highest international standards.

“Of course, the whole club, the base and the coaching staff are behind Chad, but at the end of the day, it is not the amount of people behind an athlete, but the relationship of the athlete to his environment and the quality of the applied training philosophy that make the difference. This includes the uncompromising need for the athlete’s ‘inner fire’ to be specifically pointed in the right direction.

At the end of the day, it is only the athlete himself who has to survive the hard training sets and stand alone on the starting block ready to race. Not even a high number of people around him can help. On the other hand, the training methodology has to be tailored to the athlete, and I am fully committed to this with my name and my successes.”

Dirk Lange

With that book of experience in mind, I ask the following: In the evolution of swimming and preparation of athletes, what are the areas/aspects of swimming that remain relatively unexplored that could help take swimming to the next level, not just in terms of efficiency/speed etc but in terms of making the sport a more attractive place for athletes to sign up to and stick with for longer, more fulfilling careers?

Says Lange:” You are referring to both the technical and the economic aspects of swimming. From a sporting point of view, it is clear that top athletes have to live and train like professionals. Economically, however, they are not treated as such. Therefore, the idea of a professional league, like the ISL, with many opportunities for swimmers to race and show their skills to a global audience and be rewarded with corresponding financial security, is an outstanding idea. But this concept was new and goes against everything we hold sacred in the sport of swimming.

Our sport cannot be presented like football, basketball or cycling, but has its own strengths. These must also be appreciated accordingly and we should not slide into ‘avatars’. Our DNA is and remains times, records and the Olympic Games. The swimming community is very traditional and conservative in its basic values. Turning away from this was difficult if the League wanted to achieve consistent credibility and acceptance in the swimming and media world.”

Lange notes the criticism of athletes and others who were asked to be professional but found the same due diligence was not applied by the ISL when it came to payments due and making those in a timely fashion as agreed. “This point also did not contribute to the sustainability of the League concept,” Lange noted before adding:

“On the other hand, the ISL gave the sport and athlete a new perspective on economic potential, threw out the old by embracing new competition formats. It gave rise to something fresh and that momentum should definitely be maintained. Swimming is also a professional sport, but it is a sport with its own nature, with its own fans and its own strengths.”

Dirk Lange – image: The Cali Condors Class of 2020 – photo by Mike Lewis, courtesy of the ISL

Lessons From The Lange Road

Lange is no stranger to guiding international swimmers from several countries to success in fast waters. Before, during and after his time at the helm of South African swimming, he worked specifically with Olympic and World champion Cameron van der Burgh and World champion Gerhard Zandberg. What lessons from the long Lange road might be pertinent to Chad Le Clos’ situation as a 30-year-old who has faced challenging times but talks yet of the fire in his belly? Says Lange:

In my long time as a coach, in which I worked almost exclusively internationally, the same pattern can always be seen. There are only two types of classification for athletes: successful and unsuccessful. Of course, an individual approach is needed in the training concept and athlete here and there might be said to have “used up” his or her time in swimming at a certain age. But: one should not write anyone off because of their age. Of course, physiological conditions have to be taken into account, and the ageing process cannot be reversed. It is therefore important to say goodbye to standard training solutions and find smart individual future strategies.

There is always a residual risk as a coach to get involved with a 30-year-old athlete, but I am convinced that Chad has the necessary “inner-fire” and passion to achieve his very ambitious goal for Paris 2024 – and in a way that all players in the game become winners.

Dirk Lange – Photo: Chad Le Clos in 2014, courtesy of arena

Sticking with lessons and conscious that a whole book, if not a library, could be written on the subject, I ask Lange, a coach who has worked with athletes and programs in several nations over three decades, to describe some of the key lessons learned about swimming preparation and athletes that have universal application? He replies:

“For me, the most successful places have always been those where the perspective on the sport and professionalism, the sustainability of the training philosophies and the loyalty and acceptance between the people involved hit the right note. If respect within that system is lost – between athlete and coach, or the federation, or between the federation and clubs and coaches – the success was usually of a rather short-term nature.

“This is especially true when it comes to respect for the work of the coaches and the achievements of the athletes, which is also reflected in their financial income and the security they provide for their families and education. The imbalance starts when coaches and athletes are not adequately compensated for their work, when they don’t get the respect they deserve.

“The last, but perhaps most crucial point is that such a system collapses when, for political reasons, professional decisions are made by people other than the experts. At that moment, the responsible coaches are reduced to ‘paper winners’ and there is no expertise left in the system.”

Dirk Lange – Photo: Cameron Van der Burgh, by Patrick B. Kraemer

In the context of any long career that has involved a stint in China, it is impossible not to ask what was learned from that specific experience. China is a complex place, some aspects of it less understood than they ought to be, some misunderstood and some all too well understood. What was Lange’s experience and what were some of the key upsides and downsides of the environment in which Chinese athletes work?

Says Lange: “I was allowed to work with the Chinese national swimming team for years with a few outstanding and very successful international colleagues and had my Chinese base in Shanghai. That said, I worked almost exclusively at my training sites in Europe with the Chinese athletes. The cooperation with the Chinese Swimming Federation was great.

“Certainly there are cultural differences that also have to be taken into account in the daily training work,” he added. “The athletes are very disciplined and trained incredibly hard. What was certainly surprising was the low understanding of speed work and the absolute neglect of the physical basics in the weight room. So it was more the principle: a lot helps a lot…”

His time working with the Chinese was punctuated by what for many were inevitable doubts about illicit practices, given that China had a poor record on doping and denials and certain programs led by Chinese coaches working in conditions that many other nations would not have found acceptable, fell under suspicion and were even cited as “problematic” by Western coaches working in China.

It is, of course, a vast nation, and many of those who worked in China believed that the kids and programs they worked with were swimming ‘clean’.

What upset Lange about the whole situation was what he saw as the hypocrisy and jealousy of some coaching peers.

Says Lange: “What I remember most, however, is the envy and resentment of some of my – also successful – coaching colleagues, who obviously reacted very viciously to this situation because they didn’t get the chance to get one of these lucrative contracts. They tried to stigmatise and isolate the coaches working with the Chinese – and they did that in a propaganda-like manner. There was no trace of collegiality at that time.

“My Australian colleagues can tell an even bigger story about this … there were even rumours of professional bans,” he adds. Some of it made big headlines, the late Ken Wood, mentor to Jessica Schipper, among those who copped it for being ‘traitors’ by working with Chinese programs and athletes in direct opposition to some of his former charges (like Schipper) for amounts of money they could not have dreamed of back home.

In contrast, there have been American coaches who have worked with several athletes who tested positive for doping but did not face the same kind of scrutiny and suspicion levelled at some, but by no means all, of those who worked with Chinese athletes.

“There were absurd and curious stories about betraying the sport of the Western hemisphere and sinking into the opaque web of Chinese sport,” Lange recalls. “All this happened against the background that Chinese swimming at that time posed a real sporting threat to the prevailing hegemony of world swimming.”

In one key regard it did: by the time Athens hosted the 2004 Olympic Games and Beijing had been named as 2008 host, China had the worst doping record in swimming history – and most of the athletes who tested positive were teenage girls.

“Now,” says Lange, “the Chinese sports policy orientation has changed a little.” To the extent that even inside China, Sun Yang’s fall from grace drew not only criticism of the West but also widespread criticism of Sun, his entourage, the Chinese Swimming Federation and other authorities.

On his own experience of that time, Lange looks back in sadness more than anger when he thinks of the unfounded and damaging rumours circulating at the time:

“For me personally, I can only say that even such absurdities as me holding secret training sessions with Chinese coaches were put out there when I didn’t have anything to do with the named coaches at my ‘little Turkish training centre that belonged to me’ and ‘nobody knows where it is’. Now that same centre, in Belek, has a worldwide reputation, this issue of who trains there is demonstrably off the table.

“The accusations hit me and surprised me in that my whole family from my parents-in-law, coaches and athletes themselves, to my wife, an Olympian herself [Ivana Walterová-Lange, who raced for Slovakia in the era of Martina Moravcová and is now Secretary General of the Slovak Swimming Federation and works as a full-time professional in swimming], have spent our whole lives in swimming and therefore swimming is our philosophy of life and the lifeline of our whole family.”

Dirk Lange – Photo, Lange on deck with one of the many squads he’s guided in the pool