Abuse Report Of Aussie Human Rights Boss Kate Jenkins Aimed At Self-Assessing Sports Leaders The World Over

Australia’s Human Rights Commissioner for Sex Discrimination, Kate Jenkins, released the culture review into gymnastics in Australia this week with a stark message for sports leaders staring at abuse scandals around the world: you can’t investigate yourselves and take a look at my report because it pertains to all of you, any sport, any nation.

One of the key conclusions amounts to a massive rap on the knuckles to sports authorities far and wide operating governance structures that lead to this, says Jenkins: “Athletes suffer because sports mostly investigate themselves”.

ABC’s Tracey Holmes reported: The review uncovered an environment where abuse — in all its guises — occurred because of accepted coaching practices, a focus on winning at all costs, and a complicated governance structure that is not suitable for effectively safeguarding children and young people.

“My view is all sports globally, but if I focus on Australia, all sports should look at this report. It’s very clear that a number of the risk factors that apply to gymnastics apply to all sports.”

Kate Jenkins

The Human Rights Commission’s review found those risk factors included the power imbalance between coaches and athletes and an insufficient understanding from the sport itself of what constitutes child abuse, resulting in the silencing of athlete voices and an increased risk of harm.

All sports will be sent a condensed version of the report, titled Change the Routine.

The report found many current and former gymnasts, both men and women, used the term “grooming” when speaking of their experiences.

“The abuse and mistreatment many former athletes experienced had such a profound impact on their lives that they formed a sense of hatred and rejection towards the sport,” the report said.

Sports globally are being asked how environments of abuse have been allowed to develop to the point of becoming entrenched.

Sport has no answer. Athletes are speaking out in growing numbers, sometimes decades later, after having been ignored or silenced, often with the threat of non-selection to representative teams hanging over them.

Enquiries into gymnastics have been launched in countries such as the US, the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands and New Zealand.

But it is not the only sport reckoning with its past.

Around the world, other sports such as swimming and football are also mired in historical allegations that have never suitably been addressed.

As each subsequent report is filed it becomes clear the failings are “systemic” and “institutional”.

In the United States, athletes, safe-sport advocates and others drove the bipartisan adoption and passage into law of the Empowering Olympic, Paralympic, and Amateur Athlete Act. Some of those advocates, such as Nancy Hogshead-Makar and Champion Women, have consistently and constantly highlighted the issues that serve as barriers to better culture, this challenge to an interview with a gymnastics coach – depicted in our main image – a prime example.

Abuse of athletes (among others) has become one of the hottest issues in the United States since Olympic gold medallist Deena Deardurff found the courage to make a public statement in 2010 on issues she had first reported to American swim authorities in the late 1970s and spoken of with many members of the swim community in America down the years, many of those spent as a coach.

From The Archive – An Example of Tardy Response To Abuse In Swimming

An extract from an editorial in a series on Safe Sport run by SwimVortex in March 2018 – Craig Lord

USA Swimming Handed Safe Sport Manifesto By Special Committee On Abuse 27 Years Ago

USA Swimming was handed what amounts to a manifesto matching many of the core principles of its 2010 Safe Sport program almost 27 years ago – but did not adopt key recommendations for almost 20 years after sex allegations and accompanying media coverage forced the federation’s hand.

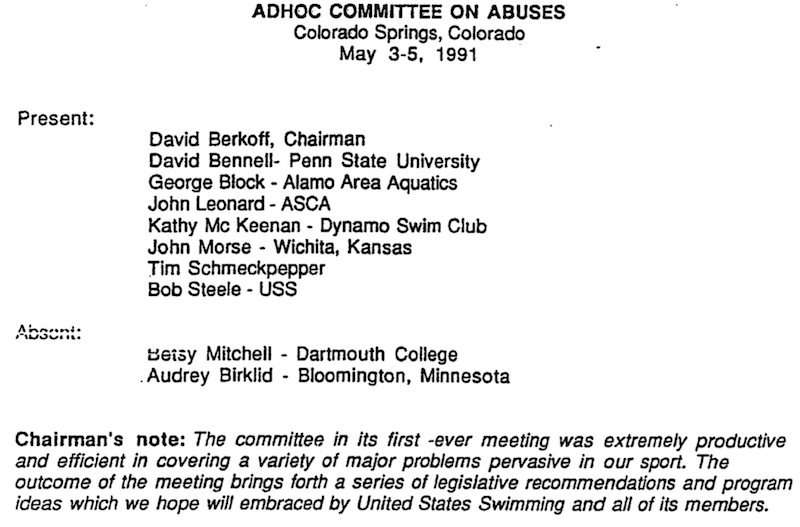

What followed, between 2010 and 2014, including the publication of what had been an internal list of banned coaches, was a long-overdue effort to pick up the pieces of a past haunted by what many now see as inaction and wilful blindness. That perception is strengthened by the minutes of a May, 1991, meeting of the ADHOC Committee on Abuses brought together by USA Swimming in Colorado Springs.

Chairman of the group was David Berkoff, the world-record-setting backstroke ace seeking to highlight abuses in swimming while still a swimmer heading for the 1992 Olympic podium as a follow-up to his 1988 Olympic podium efforts.

The minutes of the 1991 meeting take on huge significance in light of the Safe Sport scandals raging through U.S Olympic sports, the head of the United States Olympic Committee Scott Blackmun, the head of USA Swimming’s Safe Sport program Susan Woessner and head of USA Swimming club development Pat Hogan among those who have stepped down from their jobs.

A heartening and optimistic note from Berkoff heads the minutes. It reads:

“The committee, in its first-ever meeting, was extremely productive and efficient in covering a variety of major problems pervasive in our sport. The outcome of the meeting brings forth a series of legislative recommendations and program ideas, which we hope will [be] embraced by United States Swimming and all its members.”

Sadly, those relating to ‘Sexual Misconduct’ were not adopted for a great many years afterwards. In contrast, a recommendation “that all USS national team athletes be subject to random/unannounced drug testing at any time during the year” was adopted almost immediately, even though the recommendation came with the rider that “USS could never afford to test everyone” but that high moral ground taken by the USA on the issue of doping would “press FINA and the IOC into accepting random/unannounced testing internationally”.

That plan worked a treat, providing clear evidence of the power and influence of the U.S. swim federation. That power and influence was not, however, applied to the mission led by Berkoff and others to clean swimming of sex pests, perverts and abusers.

Coach representatives were ahead of the USA Swimming curve. The 1991 meeting took place two years after the American Swimming Coaches Association introduced a Code of Ethics that all members and those seeking membership were obliged to sign up to forbidding sexual relationships between coaches and swimmers of any age working under their tutelage and guidance.

The minutes of the 1991 meeting highlight that the issue of abuse in swimming in the USA was as serious back then as it has become in the past eight years since USA Swimming established its Safe Sport program.

Indeed, rules and review-board provisions covering sexual misconduct have been a part of the legislature of USA Swimming for decades. It was not until 2010, however, that the existence of a list of banned members was widely known about and made public. Today, that list stretches to some 150 coaches and others and includes some high-profile figures such as Rick Curl, jailed for abuse, Mitch Ivey and Everett Uchiyama, USA Swimming’s former U.S. National Team Director.

Critics and advocates for abuse victims say, however, that the banned list does not go nearly far enough, does not include some leading figures who face serious allegations of having had sex with under-age swimmers in their programs; does not include non-members who nonetheless continue to work in swimming in the America, a prime example that of George Gibney, the Irish coach who left for a life in the USA in the 1990s after being called out by several swimmers, girls and boys, who claim he raped and sexually assaulted them but who wait yet for justice to be served.

The minutes of the 1991 meeting highlight the urgent need for a truth and reconciliation process in the war of claim and counter claim raging at the heart and soul of USA Swimming. Such a process is also called for because some of those who now stand in the firing line of not having done enough – and even some who stand accused of having blocked measures now accepted as essential to “Safe Sport” – are no longer alive to answer for themselves.

The 1991 minutes of the Committee on Abuses suggest that there are truths to be told that would be helpful on the road to a better place but may remain hidden because of the serious risk of self-incrimination, direct or indirect, as lawyers line up with those alleging abuse that took place more than 10, 20 and even 30 years ago. Some of those making accusations entered non-disclosure agreements in which where the abuser – and, according to some evidence, the leadership of swimming – effectively bought their silence; some brought their cases to USA Swimming and others only to find their claims blocked; while others let time pass without lodging any official complaint about what they now allege to have taken place.

Who knew what and when may always be left to ‘he said, she said, they said something else’ unless those who could provide answers to pressing questions are provided with a forum that offers certain protections from criminal prosecution. Such conditions could not apply to those accused of sex crimes nor could they be extended to assurances that it will be ‘business of usual’ without loss of position and authority if a review process recommends otherwise.

The names of the leaders of USA Swimming who received recommendations for Safe Sport in 1991 are a matter of public record. Many remain in leadership positions, domestic and international.

The Committee on Abuses noted on its education plan:

“The philosophy behind this idea is that the only way to help the retention of younger athletes is to create a healthy environment for them. By educating parents, preventing abuses and ignorance within the sport, more athletes will continue with swimming rather than switch to another sport. We feel this is by far the moist productive and effective way of reaching parents; let’s give them something tangible and meaningful for their commitment and money.”

Berkoff had resigned from the committee and Board as athlete representative within two years, frustrated at the lack of progress to have recommendations turned to action.

The CRB was never founded, while it would be six years before a Board of Review and its provisions were rule-book-bound. Berkoff’s decision to move on at the age of 24, deprived USA sports governance of a key mind and an athlete keen to have his federation get to grips with the issues of abuse that were the subject of rumour and speculation as well as serious allegations, including events and processes in which athletes brought their stories to the national federation only to have them “put on the shelf or hushed up”, in the words of one victim of abuse whose case eventually led to a coach conviction.

Years, in some instances decades, went by before any of the 1991 committee’s recommendations came into effect. Some members of the committee were frustrated by the legal advice being given at the time when the issue of banning those who fell foul of sex-related misconduct came up that it would be wrong to “deny a man the right to make a living” and that such matters were best left for “the clubs to decide”. Sources say that such advice was given by legal counsel.

To add insult to injury, Berkoff’s decision to leave USA Swimming was reinforced by an incident that made a mockery of that 1991 note on the value of an education program that would “create a healthy environment” for swimmers and their parents.

Berkoff had approached Ray Essick – the then and the first Executive Director of the federation from 1980, when USS was renamed USA Swimming – to ask for help to fund an academic study he was conducting to evaluate the amount of carcinogenic chloro-organic chemicals swimmers were being exposed to in practices. The issues was particularly relevant to those who spend far more time in treated water than the general population.

According to sources present at the time, Essick responded by asking Berkoff, in so many words, ‘if it turns out that swimmers are being exposed to carcinogens do you think people might pull their kids from competitive swimming?’

Berkoff thought it might, said the source, to which Essick responded to the effect of ‘why the hell would we want to study something that might drop our membership’. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back, as far as Berkoff was concerned.

Essick is no longer here to respond to a recollection that suggests the kind of behaviour that runs through the strata of Margaret Heffernan’s excellent “Wilful Blindness – Why We Ignore The Obvious At Our Peril“.